Google just announced that a typical query to its Gemini app uses about 0.24 watt-hours of electricity. That’s about the same as running a microwave for one second—something that, to me, feels virtually insignificant. I run the microwave for so many more seconds than that on most days.

I was excited to see this report come out, and I welcome more openness from major players in AI about their estimated energy use per query. But I’ve noticed that some folks are taking this number and using it to conclude that we don’t need to worry about AI’s energy demand. That’s not the right takeaway here. Let’s dig into why.

1. This one number doesn’t reflect all queries, and it leaves out cases that likely use much more energy.

Google’s new report considers only text queries. Previous analysis, including MIT Technology Review’s reporting, suggests that generating a photo or video will typically use more electricity.

When I spoke with Jeff Dean, Google’s chief scientist, he said the company doesn’t currently have plans to do this sort of analysis for images and videos, but that he wouldn’t rule it out.

The reason the company started with text prompts is that those are something many people out there are using in their daily lives, he says, while image and video generation is something that not as many people are doing. But I’m seeing more AI images and videos all over my social feeds. So there’s a whole world of queries not represented here.

Also, this estimate is the median, meaning it’s just the number in the middle of the range of queries Google is seeing. Longer questions and responses can push up the energy demand, and so can using a reasoning model. We don’t know anything about how much energy these more complicated queries demand or what the distribution of the range is.

2. We don’t know how many queries Gemini is seeing, so we don’t know the product’s total energy impact.

One of my biggest outstanding questions about Gemini’s energy use is the total number of queries the product is seeing every day.

This number isn’t included in Google’s report, and the company wouldn’t share it with me. And let me be clear: I absolutely pestered them about this, both in a press call they had about the news and in my interview with Dean. In the press call, the company pointed me to a recent earnings report, which includes only figures about monthly active users (450 million, for what it’s worth).

“We’re not comfortable revealing that for various reasons,” Dean told me on our call. The total number is an abstract measure that changes over time, he says, adding that the company wants users to be thinking about the energy usage per prompt.

But there are people out there all over the world interacting with this technology, not just me—and what we all add up to seems quite relevant.

OpenAI does publicly share its total, sharing recently that it sees 2.5 billion queries to ChatGPT every day. So for the curious, we can use this as an example and take the company’s self-reported average energy use per query (0.34 watt-hours) to get a rough idea of the total for all people prompting ChatGPT.

According to my math, over the course of a year, that would add up to over 300 gigawatt-hours—the same as powering nearly 30,000 US homes annually. When you put it that way, it starts to sound like a lot of seconds in microwaves.

3. AI is everywhere, not just in chatbots, and we’re often not even conscious of it.

AI is touching our lives even when we’re not looking for it. AI summaries appear in web searches, whether you ask for them or not. There are built-in features for email and texting applications that that can draft or summarize messages for you.

Google’s estimate is strictly for Gemini apps and wouldn’t include many of the other ways that even this one company is using AI. So even if you’re trying to think about your own personal energy demand, it’s increasingly difficult to tally up.

To be clear, I don’t think people should feel guilty for using tools that they find genuinely helpful. And ultimately, I don’t think the most important conversation is about personal responsibility.

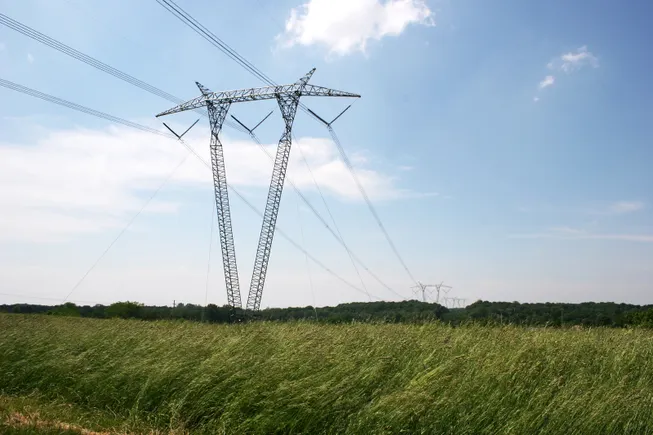

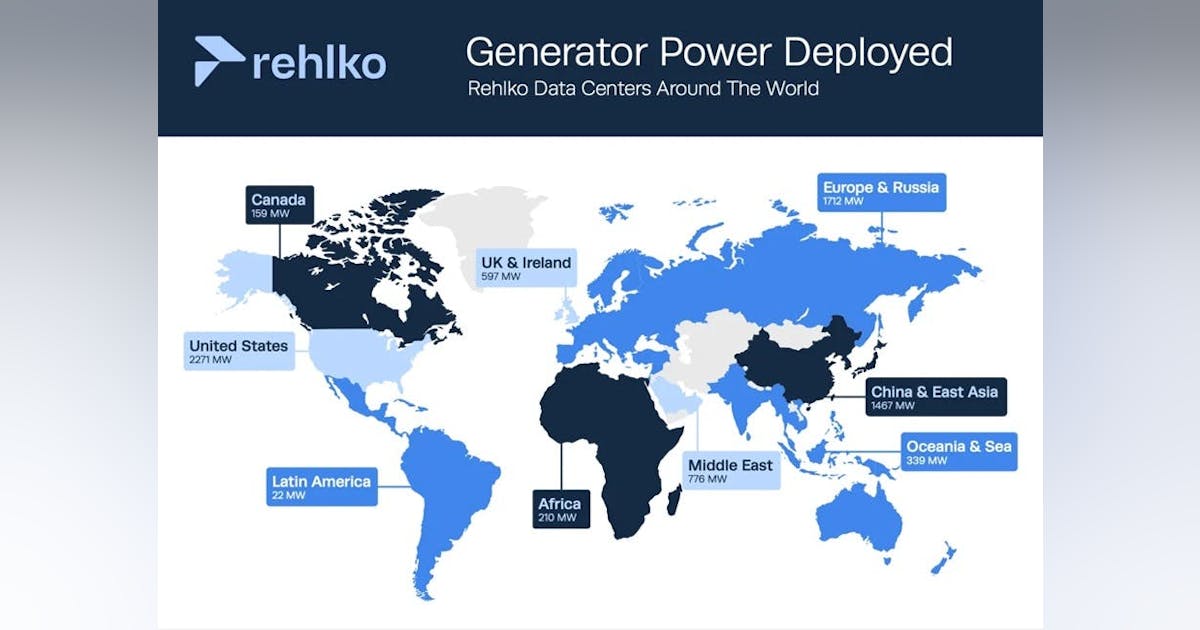

There’s a tendency right now to focus on the small numbers, but we need to keep in mind what this is all adding up to. Over two gigawatts of natural gas will need to come online in Louisiana to power a single Meta data center this decade. Google Cloud is spending $25 billion on AI just in the PJM grid on the US East Coast. By 2028, AI could account for 326 terawatt-hours of electricity demand in the US annually, generating over 100 million metric tons of carbon dioxide.

We need more reporting from major players in AI, and Google’s recent announcement is one of the most transparent accounts yet. But one small number doesn’t negate the ways this technology is affecting communities and changing our power grid.

This article is from The Spark, MIT Technology Review’s weekly climate newsletter. To receive it in your inbox every Wednesday, sign up here.