On a typical afternoon, MIT’s new Edward and Joyce Linde Music Building hums with life. On the fourth floor, a jazz combo works through a set in a rehearsal suite as engineers adjust microphone levels in a nearby control booth. Downstairs, the layered rhythms of Senegalese drumming pulse through a room built to absorb its force. In the building’s makerspace, students solder circuits, prototype sensor systems, and build instruments. Just off the main lobby, beneath the 50-foot ceiling of the circular Thomas Tull Concert Hall, another group tests how the room, whose acoustics can be calibrated to shift with each performance, responds to its sound.

Situated behind Kresge Auditorium on the site of a former parking lot, the Linde building doesn’t mark the beginning of a serious commitment to music at MIT—it amplifies an already strong program. Every year, more than 1,500 students enroll in music classes, and over 500 take part in one of the Institute’s 30 ensembles, from the MIT Symphony Orchestra to the Fabulous MIT Laptop Ensemble, which creates electronic music using laptops and synthesizers. They rehearse and perform in venues across campus, including Killian Hall, Kresge, and a network of practice rooms, but the Linde Building provides a dedicated home to meet the depth, range, and ambition of music at MIT.

“It would be very difficult to teach biology or engineering in a studio designed for dance or music,” Jay Scheib, section head for Music and Theater Arts, told MIT News shortly before the building officially opened. “The same goes for teaching music in a mathematics or chemistry classroom. In the past, we’ve done it, but it did limit us.” He said the new space would allow MIT musicians to hear their music as it was intended to be heard and “provide an opportunity to convene people to inhabit the same space, breathe the same air, and exchange ideas and perspectives.”

The building, made possible by a gift from the late philanthropists Edward ’62 and Joyce Linde, has already transformed daily music life on campus. Musicians, engineers, and designers now cross paths more often as they make use of its rehearsal rooms, performance spaces, studios, and makerspace, and their ideas have begun converging in distinctly MIT ways. Antonis Christou, a second-year master’s student in the Opera of the Future group at the MIT Media Lab and an Emerson/Harris Scholar, says he’s there “all the time” for classes, rehearsals, and composing.

“It’s really nice to have a dedicated space for music on campus. MIT does have very strong music and arts programs, so I think it reflects the strength of those programs,” says Valerie Chen ’22, MEng ’23, a cellist and PhD candidate in electrical engineering who works on interactive robotics. “But more than that, I think it makes a statement that technology and the arts, and music in particular, are very interconnected.”

A building tuned for acoustics and performance

Acoustic innovation shaped every aspect of the building’s 35,000 square feet of space. From the outset, the design team faced a fundamental challenge: how to create a facility where radically different types of music could coexist without interference. Keeril Makan, the Michael (1949) and Sonja Koerner Music Composition Professor and associate dean of MIT’s School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences (SHASS), helped lead that effort.

“It was important to me that we could have classical music happening in one space, world music in another space, jazz somewhere else, and also very fine measurements of sound all happening at the same time. And it really does that,” says Makan. “But it took a lot of work to get there.”

That work resulted in a building made up of three artfully interconnected blocks, creating three acoustically isolated zones: the Thomas Tull Concert Hall, the Erdely Music and Culture Space, and the Lim Music Maker Pavilion. Thick double shells of concrete enclose each zone, and their physical separation minimizes vibration transfer between them. One space for world music rests on a floating slab above the building’s underground parking garage and is constructed using a box-in-box method, with its inner room structurally isolated from the rest of the building. Other rooms use related techniques, with walls, floors, and ceilings separated by layers of sound-dampening materials and structural isolation systems to reduce sound transmission.

The building was designed by the Japanese architecture firm SANAA, in close collaboration with Nagata Acoustics, the team behind Berlin’s Pierre Boulez Saal. Inspired in part by that German hall, the 390-seat Thomas Tull Concert Hall is meant to serve musicians’ varying acoustic needs. Inside, ceiling baffles and perimeter curtains make it possible to adapt the room on demand, shifting the acoustics from resonant and open for chamber music and classical performances to drier and more controlled for jazz or electronic music.

Makan and the acoustics team pushed for a 50-foot ceiling, a requirement from Nagata for acoustic flexibility and performance quality. The result is a concert hall that breaks from traditional form. Instead of occupying a raised stage facing rows of seats, performers in Tull Hall are positioned at the bottom of the space, with the audience seated around and above them. This layout alters the relationship between listeners and performers; audience members can choose to sit next to the string section or behind the pianist, experiencing sounds and sights typically reserved for musicians. The circular configuration encourages movement, intimacy, and a more immersive musical experience.

“It’s a big opportunity for creativity,” says Ian Hattwick, a lecturer in music technology. “You can distribute musicians around the hall in interesting ways. I really encourage people in electronic music concerts to come up and get close. You can come up and peer over somebody’s shoulder while they’re playing. It’s definitely different. But I think it’s beautiful.”

That sense of openness shaped one of the first performances in the new hall. As part of the building’s opening-weekend event in February, called “Sonic Jubilance,” the Fabulous MIT Laptop Ensemble (FaMLE), directed by Hattwick, took the stage, testing the venue’s variable acoustics and capacity for spatial experimentation as it employed laptops, gestural controllers, and other electronic devices to improvise and perform electronic music.

“I was really struck by how good it sounded for what I do and for what FaMLE does,” says Hattwick. “There’s a surround system of speakers. It was really fun and really satisfying, so I’m super excited to spend some more time working on spatial audio applications.” That evening, a concert featured performances by a diverse array of additional ensembles and world premieres by four MIT composers. It was the first moment many performers heard what the hall could do—and the first time they’d shared a space designed for all of them.

The community joined MIT music faculty, staff, and students for special workshops and short performances at the building’s public opening in February.

Since then, the hall has hosted a wide range of performances, from student recitals to concerts featuring guest artists. In the span of two weeks in March, the Boston Chamber Music Society celebrated the music of Fauré and the Boston Symphony Chamber Players performed works by Aaron Copland, Brahms, and MIT’s own Makan. Other concerts have featured student compositions, historical instruments, and multichannel electronic works.

Just a few steps from the entrance to Tull Concert Hall, across the brick- and glass-lined lobby, the Beatrice and Stephen Erdely Music and Culture Space supports a different kind of sound. It’s designed to host rehearsals of percussion groups like Rambax MIT, the Institute’s Senegalese drumming ensemble, which uses hand-carved sabar drums, each played with a stick and open palm to produce tightly woven polyrhythms. At other times, students gather there around bronze-keyed instruments as they play with the Gamelan Galak Tika ensemble, practicing the interlocking patterns of Balinese kotekan.

Such music was originally meant to be performed in the open. The Music and Culture Space provides the physical and sonic headroom these traditions require, using materials chosen not only to isolate sound but also to let it breathe. Inside, the room thrums with rhythm, while just outside its walls, the rest of the building stays silent.

“We can imagine [world music] growing with this new home,” says Makan. Previously, these ensembles had rehearsed in a converted space inside the old MIT Museum building on Massachusetts Avenue, separated from the rest of the music program.

“They deserved their own space for so long,” says Hattwick, “and it’s really fantastic that they managed to get it and that it is integrated in the music building the way that it is.”

The building’s commitment to sound isolation extends beyond its rehearsal and performance spaces, and for faculty working in sound design and music technology, it has changed their daily rhythms. Mark Rau, an assistant professor of music technology with a joint appointment in electrical engineering and computer science (EECS), regularly uses speakers at high volume in his office—something that he says wouldn’t have been possible in MIT’s previous facilities.

“All the rooms in the building have good sound isolation, even the offices—not just the performance rooms, which is pretty great,” says Rau, whose second-floor office in the Jae S. and Kyuho Lim Music Maker Pavilion features gray acoustic panels lining the walls and ceiling. “To be able to test the algorithms that I’m working on and things for homework assignments, and not bother my neighbors, is important.”

The attention to acoustic detail continues upstairs. On the fourth floor, Rau ran the first two sessions in the building’s new recording facilities, which were purpose-built to support both ensemble work and critical listening. He says they offer professional-quality recording.

The recording suite includes a large main room that can accommodate up to a dozen players, a smaller isolation booth for separating instruments or voices, and a control room designed for precise monitoring. Each space is acoustically treated and linked to the building’s dedicated audio network, so sound can be routed from any room in the building to any other in real time.

“You could record an entire symphony orchestra, and almost everybody could be in a different room,” says Hattwick. Or you could have the orchestra playing together in the concert hall and record it in one of the studios. The whole building uses a digital audio protocol called Dante, which allows low-latency, high-fidelity transmission over Ethernet.

MIT multimedia specialist Cuco Daglio, who helped oversee technical planning, advocated for that level of fidelity. “It’s a beautifully designed acoustic space,” says Hattwick.

The building’s exterior reflects a similar attention to performance. The arch above its entryway facing the Johnson Athletic Center and the Zesiger Sports and Fitness Center forms a conical shell that shapes and reflects sound, creating a natural stage. On warm days, music drifts out into the open air as groups rehearse beneath the overhang or students gather to play informally in small groups.

New program, new space

This fall, MIT is launching a new one-year master’s program in music technology, bringing together faculty from engineering and the arts. The Linde Music Building serves as the program’s home base, providing studios, tools, and collaborative spaces that students will use to design new instruments, software, and performance systems. Eran Egozy ’93, MEng ’95, professor of the practice in music technology and cofounder of Harmonix Music Systems, which developed Guitar Hero and Rock Band, directs the program. He developed the curriculum with Anna Huang, SM ’08, an associate professor with a joint appointment in music and EECS who did research on human-AI music collaboration technologies at Google, and he, Huang, and Rau are among its faculty.

“It’s really about inventing new things,” says Egozy. “Asking questions like: What would the future musician want? What kinds of tools will a composer want?”

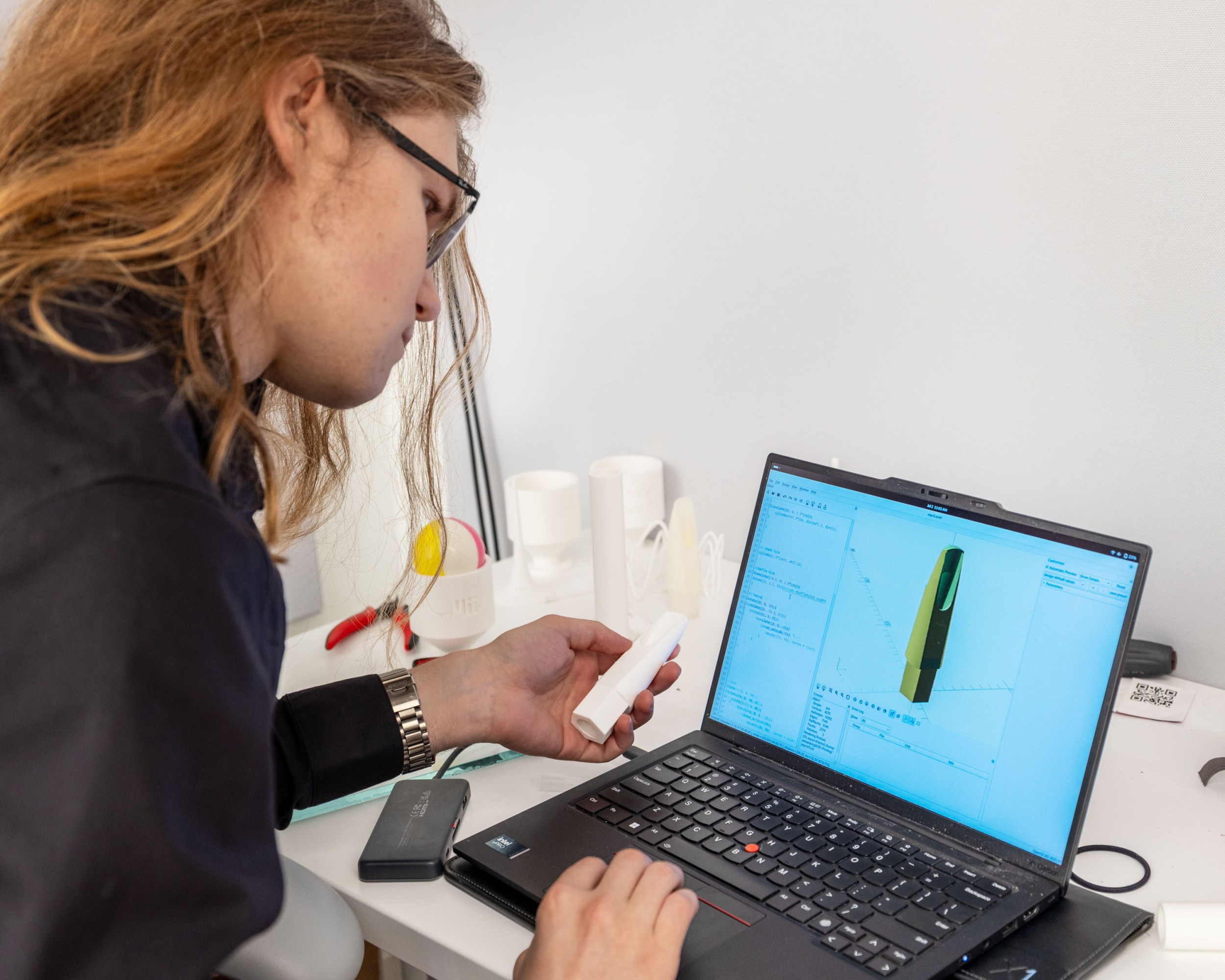

Rachel Loh ’25, who double-majored in computer science and engineering and music, will be part of the inaugural cohort. A vocalist with Syncopasian, MIT’s East Asian a cappella group, she draws on performance experience in her research. Her current project explores how AI systems improvise alongside human musicians, using visualizations to provide insight into machine decision-making.

“In high school, I knew I wanted to work at the intersection of music and computer science,” she says. “Now, this new music tech program is the perfect thing for me.”

A flexible workshop on the Music Maker Pavilion’s second floor will serve as a core space for the new program, outfitted with essentials like soldering stations, a laser cutter, and testing gear but left unfinished by design. Hattwick and Rau, who oversee the space, are allowing its exact form to emerge over time.

“We’ve been spending this year outfitting it and starting to think about how we make all of these resources available to our students, and what the best way is to utilize this opportunity in this space,” Hattwick says. “[The makerspace] directly supports research and our specific coursework.”

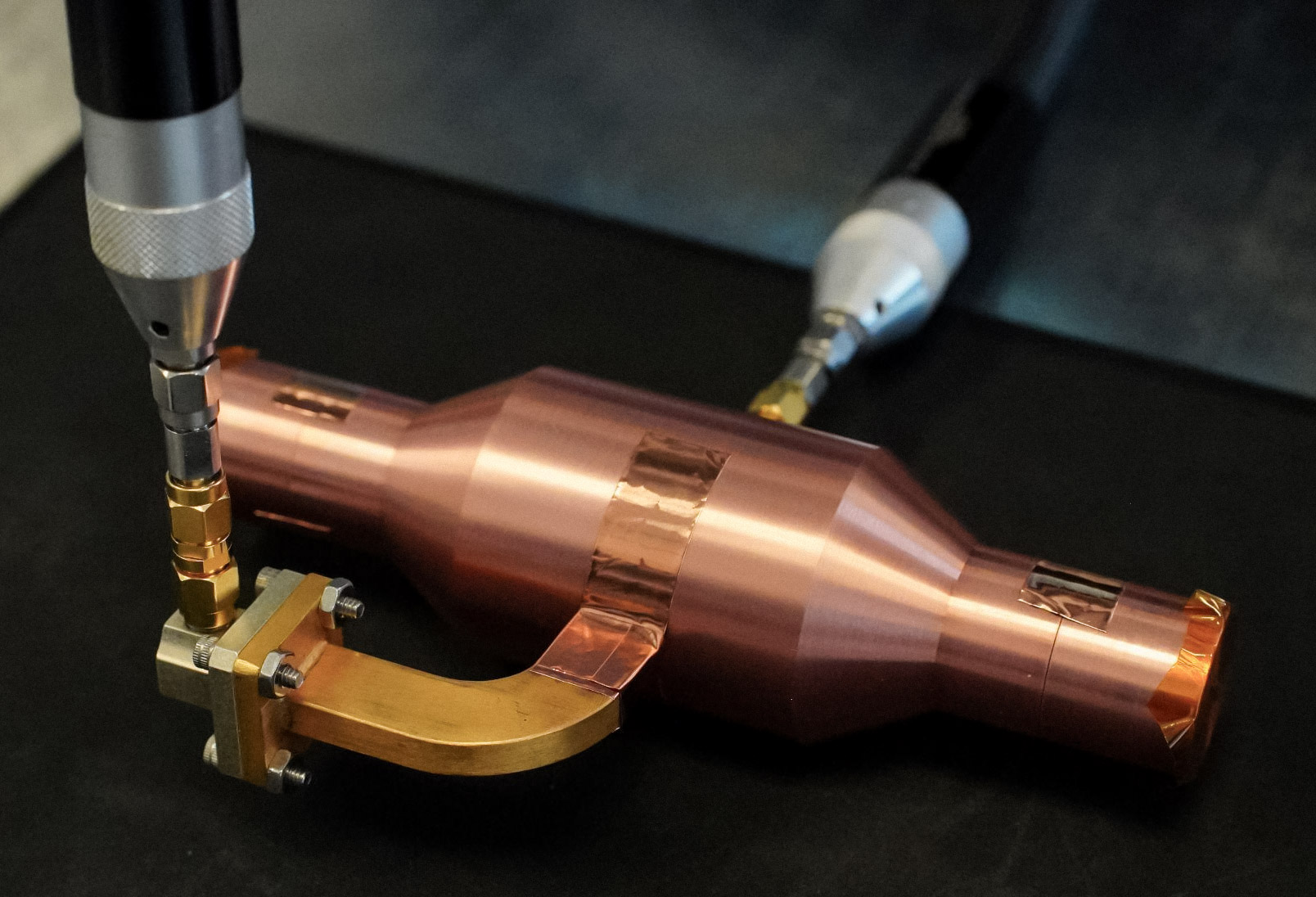

Already, students have begun to push the makerspace into new territory. Some are designing analog circuits and signal-boosting devices known as preamplifiers for musical instrument sensors. Others are experimenting with embedded systems that blur the boundary between physical and digital sound. In one class, students are building custom digital instruments from scratch—tools that don’t yet exist, shaped to suit musical ideas still in formation. The building’s infrastructure, including features like Dante, gives these projects unusual flexibility.

Ayyub Abdulrezak ’24, MEng ’25, one of Egozy’s students, worked in the makerspace to develop compact sensor boxes that combine a microphone, a Raspberry Pi board, and custom signal-processing software. Each device logs when and how long a campus piano is played, sending the data to a central server. The resulting heat maps could help inform tuning schedules, improve access, or guide planning for music spaces across MIT.

The makerspace also supports repair, maintenance, and modification. Hattwick describes it as a place to “build and fix and maintain and explore new kinds of instruments,” where students can learn what it means to refine a musical system—not just in theory but in screws, solder, and code. Rau, who also builds guitars, is incorporating more hands-on fabrication into his courses, merging electronics with instrument making and repair to yield a unified design practice.

While the space is still growing into its full potential, its ethos is clear: experimentation at the intersection of sound, system, and student agency. These kinds of projects rely not only on equipment but on space where musicians can experiment, fail, and refine. As the new master’s program takes shape, that environment will be central to how students learn and create.

Building sound and community

For the first time, MIT musicians, technologists, composers, and researchers share a space designed to bring their disciplines into conversation. The building’s form encourages these exchanges. Its three wings connect through a glass-lined lobby filled with daylight and movement. Students pause there to talk, overhear a rehearsal in progress, or catch sight of a friend heading to a practice room.

“Music is such a community thing,” says Christou. “I’ve learned about concerts, or that someone is coming to visit, or I’ve seen friends just studying or practicing. It’s really nice to have a hub with musical activity.”

Egozy sees these exchanges as central to the building’s mission. “It’s the idea cross-pollination that happens when you just happen to run into someone you know, literally by the water cooler, and you’re just chatting about this or that,” he says. “That’s my favorite part.”

Many of these encounters occur in the makerspace, where students working on entirely different projects end up asking each other questions, swapping tools, or launching ideas together.

“Lots of students from all different walks of life have been building instruments, prototyping different devices,” says Makan, who adds that he wants the new building to be “a place for people to gather and hang out.” Many ensembles that once rehearsed in classrooms scattered across campus now work in adjoining rooms. “You feel like something is always happening,” Christou says. “It’s not just your practice or your rehearsal. It’s this sense of a shared rhythm.”

New frontiers for MIT’s music culture

Already, the Linde Music Building is affecting how music is conceived, taught, and experienced at MIT. Faculty members are rethinking syllabi to take advantage of the building’s multi-room routing capability and to delve more into spatial acoustics, interactive sound design, and even instrument making. Students are beginning to compose with acoustics in mind, treating the building itself as part of their instrument.

For example, Rau is engaging students in projects that explore room dynamics and acoustics as integral to music. In one class, students listen for differences in how music sounds in various parts of Tull Hall and observe changes when the curtains are used. Then they conduct acoustic measurements of the hall’s reverberation and build a digital copy of the hall, creating a sonic blueprint of the space that lets them produce artificial reverberation. Egozy, meanwhile, is developing tools that let performers engage audiences in new ways.

This June, one of those ideas was scaled up. As part of the International Computer Music Conference, MIT premiered a piece that invited audience members to shape the sound in real time using their phones. Musicians performed in Tull Hall, surrounded by a circular array of 24 speakers, with the audio shifting throughout the space in response to the audience input.

Performances like these are fueling growing interest in the building’s creative potential at MIT and beyond. Visiting composers have proposed site-specific works. Local ensembles are booking time to record in Tull Hall. Faculty are exploring how the building might support residencies that pair MIT researchers with performers working at the leading edges of both sound and computation.

“This hall is really special. There’s nothing like it anywhere in the Boston area,” Egozy says. “We will have a lot of really amazing events that will draw people into MIT. We’re excited about what it’s going to do for the MIT students, but it’s also going to do a lot just for the whole Boston area.”

Each day, students and faculty explore its possibilities—linking rehearsal with recording, sound design with performance, tradition with experiment.

MIT is “a place to enable exploration of new vistas, and really letting everyone pursue their path to what their vision is,” Hattwick says. “The music building is just going to be like a huge boost to doing even more cool things in the future.”