For just the second time in nearly two decades, the United States has granted an export license to an American company planning to sell nuclear technology to India, MIT Technology Review has learned. The decision to greenlight Clean Core Thorium Energy’s license is a major step toward closer cooperation between the two countries on atomic energy and marks a milestone in the development of thorium as an alternative to uranium for fueling nuclear reactors.

Starting from the issuance last week, the thorium fuel produced by the Chicago-based company can be shipped to reactors in India, where it could be loaded into the cores of existing reactors. Once Clean Core receives final approval from Indian regulators, it will become one of the first American companies to sell nuclear technology to India, just as the world’s most populous nation has started relaxing strict rules that have long kept the US private sector from entering its atomic power industry.

“This license marks a turning point, not just for Clean Core but for the US-India civil nuclear partnership,” says Mehul Shah, the company’s chief executive and founder. “It places thorium at the center of the global energy transformation.”

Thorium has long been seen as a good alternative to uranium because it’s more abundant, produces both smaller amounts of long-lived radioactive waste and fewer byproducts with centuries-long half-lives, and reduces the risk that materials from the fuel cycle will be diverted into weapons manufacturing.

But at least some uranium fuel is needed to make thorium atoms split, making it an imperfect replacement. It’s also less well suited for use in the light-water reactors that power the vast majority of commercial nuclear plants worldwide. And in any case, the complex, highly regulated nuclear industry is extremely resistant to change.

For India, which has scant uranium reserves but abundant deposits of thorium, the latter metal has been part of a long-term strategy for reducing dependence on imported fuels. The nation started negotiating a nuclear export treaty with the US in the early 2000s, and a 123 Agreement—a special, Senate-approved treaty the US requires with another country before sending it any civilian nuclear products—was approved in 2008.

A new approach

While most thorium advocates have envisioned new reactors designed to run on this fuel, which would mean rebuilding the nuclear industry from the ground up, Shah and his team took a different approach. Clean Core created a new type of fuel that blends thorium with a more concentrated type of uranium called HALEU (high-assay low-enriched uranium). This blended fuel can be used in India’s pressurized heavy-water reactors, which make up the bulk of the country’s existing fleet and many of the new units under development now.

Thorium isn’t a fissile material itself, meaning its atoms aren’t inherently unstable enough for an extra neutron to easily split the nuclei and release energy. But the metal has what’s known as “fertile properties,” meaning it can absorb neutrons and transform into the fissile material uranium-233. Uranium-233 produces fewer long-lived radioactive isotopes than the uranium-235 that makes up the fissionable part of traditional fuel pellets. Most commercial reactors run on low-enriched uranium, which is about 5% U-235. When the fuel is spent, roughly 95% of the energy potential is left in the metal. And what remains is a highly toxic cocktail of long-lived radioactive isotopes such as cesium-137 and plutonium-239, which keep the waste dangerous for tens of thousands of years. Another concern is that the plutonium could be extracted for use in weapons.

Enriched up to 20%, HALEU allows reactors to extract more of the available energy and thus reduce the volume of waste. Clean Core’s fuel goes further: The HALEU provides the initial spark to ignite fertile thorium and triggers a reaction that can burn much hotter and utilize the vast majority of the material in the core, as a study published last year in the journal Nuclear Engineering and Design showed.

“Thorium provides attributes needed to achieve higher burnups,” says Koroush Shirvan, an MIT professor of nuclear science and engineering who helped design Clean Core’s fuel assemblies. “It is enabling technology to go to higher burnups, which reduces your spent fuel volume, increases your fuel efficiency, and reduces the amount of uranium that you need.”

Compared with traditional uranium fuel, Clean Core says, its fuel reduces waste by more than 85% while avoiding the most problematic isotopes produced during fission. “The result is a safer, more sustainable cycle that reframes nuclear power not as a source of millennia-long liabilities but as a pathway to cleaner energy and a viable future fuel supply,” says Milan Shah, Clean Core’s chief operating officer and Mehul’s son.

Pressurized heavy-water reactors are particularly well suited to thorium because heavy water—a version of H2O that has an extra neutron on the hydrogen atom—absorbs fewer neutrons during the fission process, increasing efficiency by allowing more neutrons to be captured by the thorium.

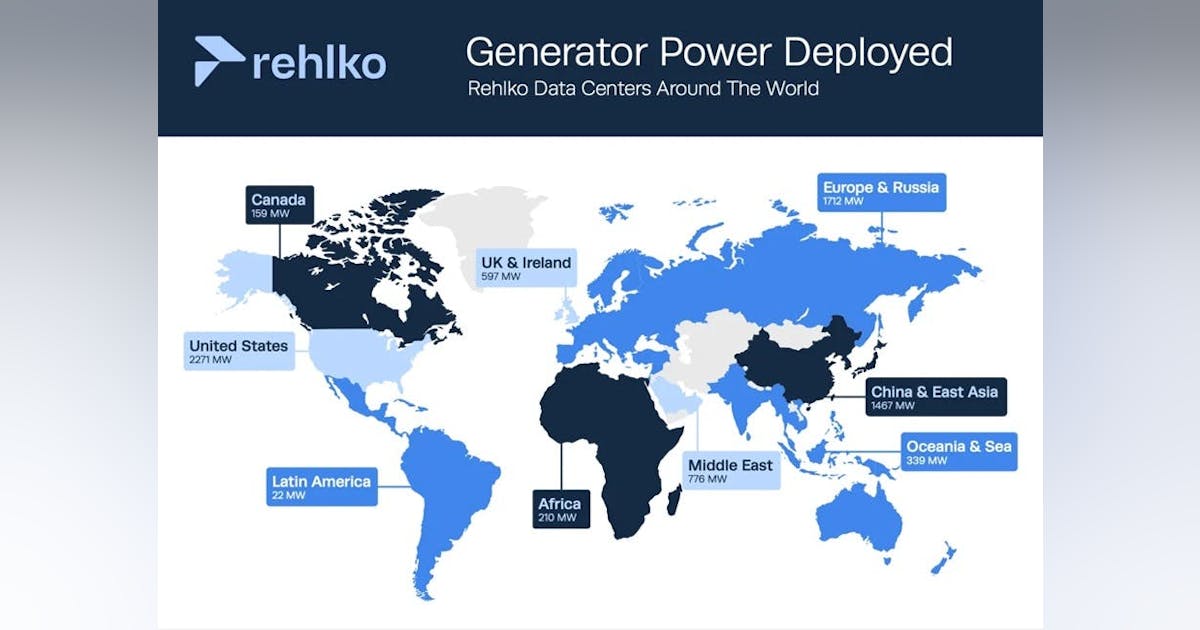

There are 46 so-called PHWRs operating worldwide: 17 in Canada, 19 in India, three each in Argentina and South Korea, and two each in China and Romania, according to data from the International Atomic Energy Agency. In 1954, India set out a three-stage development plan for nuclear power that involved eventually phasing thorium into the fuel cycle for its fleet.

Yet in the 56 years since India built its first commercial nuclear plant, its state-controlled industry has remained relatively shut off to the private sector and the rest of the world. When the US signed the 123 Agreement with India in 2008, the moment heralded an era in which the subcontinent could become a testing ground for new American reactor designs.

In 2010, however, India passed the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act. The legislation was based on what lawmakers saw as legal shortcomings in the wake of the 1984 Bhopal chemical factory disaster, when a subsidiary of the American industrial giant Dow Chemical avoided major payouts to the victims of a catastrophe that killed thousands. Under this law, responsibility for an accident at an Indian nuclear plant would fall on suppliers. The statute effectively killed any exports to India, since few companies could shoulder that burden. Only Russia’s state-owned Rosatom charged ahead with exporting reactors to India.

But things are changing. In a joint statement issued after a February 2025 summit, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and President Donald Trump “announced their commitment to fully realise the US-India 123 Civil Nuclear Agreement by moving forward with plans to work together to build US-designed nuclear reactors in India through large scale localisation and possible technology transfer.”

In March 2025, US federal officials gave the nuclear developer Holtec International an export license to sell Indian companies its as-yet-unbuilt small modular reactors, which are based on the light-water reactor design used in the US. In April, the Indian government suggested it would reform the nuclear liability law to relax rules on foreign companies in hopes of drawing more overseas developers. Last month, a top minister confirmed that the Modi administration would overhaul the law.

“For India, the thing they need to do is get another international vendor in the marketplace,” says Chris Gadomski, the chief nuclear analyst at the consultancy BloombergNEF.

Path of least resistance

But Shah sees larger potential for Clean Core. Unlike Holtec, whose export license was endorsed by the two Mumbai-based industrial giants Larsen & Toubro and Tata Consulting Engineers, Clean Core had its permit approved by two of India’s atomic regulators and its main state-owned nuclear company. By focusing on fuel rather than new reactors, Clean Core could become a vendor to the majority of the existing plants already operating in India.

Its technology diverges not only from that of other US nuclear companies but also from the approach used in China. Last year, China made waves by bringing its first thorium-fueled reactor online. This enabled it to establish a new foothold in a technology the US had invented and then abandoned, and it gave Beijing another leg up in atomic energy.

But scaling that technology will require building out a whole new kind of reactor. That comes at a cost. A recent Johns Hopkins University study found that China’s success in building nuclear reactors stemmed in large part from standardization and repetition of successful designs, virtually all of which have been light-water reactors. Using thorium in existing heavy-water reactors lowers the bar for popularizing the fuel, according to the younger Shah.

“We think ours is the path of least resistance,” Milan Shah says. “Maybe not being completely revolutionary in the way you look at nuclear today, but incredibly evolutionary to progress humanity forward.”

The company has plans to go beyond pressurized heavy-water reactors. Within two years, the elder Shah says, Clean Core plans to design a version of its fuel that could work in the light-water reactors that make up the entire US fleet of 94. But it’s not a simple conversion. For starters, there’s the size: While the PHWR fuel rods are about 50 centimeters in length, the rods that go into light-water reactors are roughly four meters long. Then there’s the history of challenges with light water’s absorption of neutrons that could otherwise be captured to induce fission in the thorium.

For Anil Kakodkar, the former chairman of India’s Atomic Energy Commission and a mentor to Shah, popularizing thorium could help rectify one of the darker chapters in his country’s nuclear development. In 1974, India became the first country since the signing of the first global Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons to successfully test an atomic weapon. New Delhi was never a signatory to the pact. But the milestone prompted neighboring Pakistan to develop its own weapons.

In response, President Jimmy Carter tried to demonstrate Washington’s commitment to reversing the Cold War arms race by sacrificing the first US effort to commercialize nuclear waste recycling, since the technology to separate plutonium and other radioisotopes from uranium in spent fuel was widely seen as a potential new source of weapons-grade material. By running its own reactors on thorium, Kakodkar says, India can chart a new path for newcomer nations that want to harness the power of the atom without stoking fears that nuclear weapons capability will spread.

“The proliferation concerns will be dismissed to a significant extent, allowing more rapid growth of nuclear power in emerging countries,” he says. “That will be a good thing for the world at large.”

Alexander C. Kaufman is a reporter who has covered energy, climate change, pollution, business, and geopolitics for more than a decade.