Dive Brief:

- Significant load growth is likely to arrive as forecast, but uncertainties associated with data centers are complicating load growth estimation, as are “unrealistically high load factors for the new large loads” in some load forecasts, said John Wilson, a vice president at Grid Strategies.

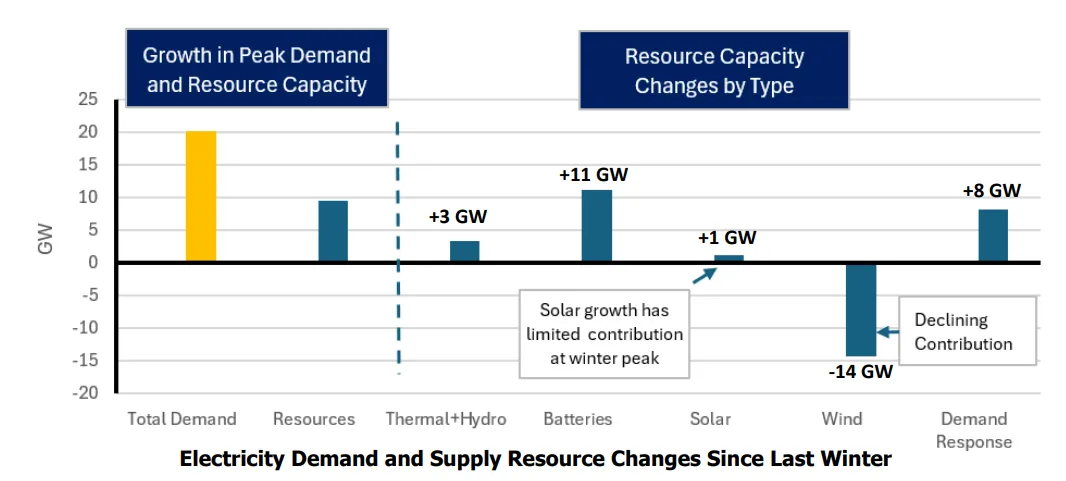

- Wilson is one of the lead authors of a November report which found the five-year forecast of U.S. utility peak load growth has increased from 24 GW to 166 GW over the past three years — by more than a factor of six.

- The report concluded that the “data center portion of utility load forecasts is likely overstated by roughly 25 GW,” based on reports from market analysts.

Dive Insight:

Despite projected load growth, many utility third-quarter earnings reports have shown relatively flat deliveries of electricity. Wilson said he thinks a definitive answer as to whether or not load growth is materializing will come next year.

“If [large loads] start to get put off or canceled, and the load doesn’t come in, then we could see a lot of revisions to forecasts that are really large,” he said.

The utility forecast for added data center load by 2030 is 90 GW, “nearly 10% of forecast peak load,” the report said, but “data center market analysts indicate that data center growth is unlikely to require much more than 65 GW through 2030.”

Wilson said he thinks the overestimation could be due “simply to the challenge that utilities have in understanding whether a potential customer is pursuing just the site in their service area, or whether they’re pursuing multiple sites and they’re not planning on building out all of them.”

This is information that utilities haven’t typically gathered, he said, although he’s seeing a trend toward utilities making those questions part of their application process. Wilson said another factor is whether the companies are being honest about their plans, or whether they “even know the answer to that question internally — maybe that answer is known by a few top C-suite people, but not by the line staff.”

A third factor is schedule, he said.

“It could be that the 90 GW is going to happen, but as a lot of data centers get built out, and you start to see supply chain constraints — backlogged orders for chips and other key components — schedules start to slip,” he said. “Six months here, eight months there. And that can mean that the 90 GW is a perfectly accurate number, just not for 2030. Maybe it’s 2032 that we hit that.”

Wilson noted that “we’re still talking about somewhere in the neighborhood of 140 GW of growth over the next five years. So I wouldn’t call this an overestimate that changes the story.”

The report also found that “electricity use is forecast to increase even more quickly than peak power demand,” and by 2030, “forecasts indicate that total electricity use will increase by 32%.”

This reflects the high load factors of data centers “as well as forecast changes in off-peak energy use by other customers,” the report said. “The high-energy character of forecast load growth will change the way planners expect the grid to operate. The higher growth rate for energy can be measured as a 96% load factor for new energy and peak demand.”

The report authors suspect “that some of the large load forecasts may be using unrealistically high load factors for the new large loads,” Wilson said, such as a 95% to 100% load factor.

“There may be individual facilities that are going to operate at that level, but that’s going to be really hard and rare to do because throughout the year you’ll have a week where you have to take the facility down for some major maintenance or something, it’s just part of the business,” he said.

Wilson said he originally thought the estimated 96% load factor for new energy and peak demand was a mistake.

“I just couldn’t imagine that we were seeing enough energy growth that, basically, for every new gigawatt of capacity you were at, it was going to be running 96% of the time, year-round. That just was mind-blowing,” he said. “For that to be the national average was really surprising.”

Data centers account for about 55% of demand growth in utility load forecasts over the next five years, the report said, but “new load for industrial/manufacturing, oil & gas/mining, and other load types is large compared to recent decades.”

Industry and manufacturing are estimated to drive around 30 GW of load growth by 2030, and other factors, like building and transportation electrification, are anticipated to drive another 30 GW.

There is “less uncertainty” than with data centers, “but still significant uncertainty” present when forecasting demand for the other sources of load growth, Wilson said.

“It’s very challenging at this point in time for load forecasts to be accurate,” he said. “And, I mean, they never have been. But even now, you’re having to develop new methods for forecasting, for a whole new set of drivers, in … no time at all. You have no time to test them and refine the methods. You just have to publish the results and hope you’re right.”