The AI data center is no longer just a building full of racks. It is a system: dense, interdependent, and increasingly unforgiving of bad assumptions.

That reality sits at the center of the latest episode of The Data Center Frontier Show, where DCF Editor-in-Chief Matt Vincent sits down with Sherman Ikemoto, Senior Director of Product Management at Cadence, to talk about what it now takes to design an “AI factory” that actually works.

The conversation ranges from digital twins and GPU-dense power modeling to billion-cycle power analysis and the long-running Cadence–NVIDIA collaboration. But the through-line is simple: the industry is outgrowing rules of thumb.

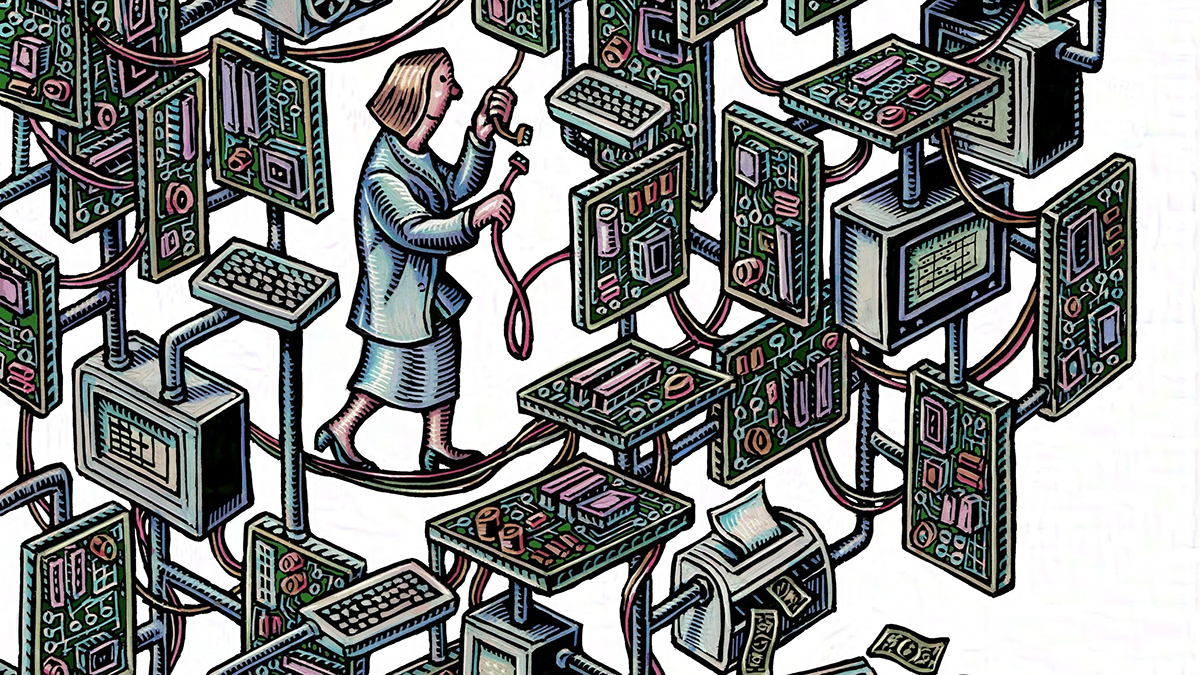

As Ikemoto puts it, data center design has always been a distributed process. Servers are designed by one set of suppliers, cooling by another, power by another. Only at the end does the operator attempt to integrate those parts into a working system.

That final integration phase, he argues, has long been underserved by design tools. The risk shows up later, as downtime, cost overruns, or performance shortfalls.

Cadence’s answer is a new class of digital infrastructure: what it calls “DC elements,” validated building blocks that let operators assemble and simulate an AI factory before they ever pour concrete.

The DGX SuperPOD as a Digital Building Block

One of the most significant recent additions is a full behavioral model of NVIDIA’s DGX SuperPOD built around GB200 systems. This is not just a geometry file or a thermal sketch. It is a behaviorally accurate digital representation of how that system consumes power, moves heat, and interacts with airflow and liquid cooling.

In practice, that means an operator can drop a DGX SuperPOD element into a digital design and immediately see how it stresses the rest of the facility: power distribution, cooling loops, airflow patterns, and failure scenarios.

Ikemoto describes these as “DC elements”: digital building blocks that bridge the gap between suppliers and operators. Each element carries real performance data from the vendor, validated through a star-rating system that measures how closely the model matches real-world behavior.

The highest rating, five stars, requires strict validation and supplier sign-off. The GB200 DGX SuperPOD element reached that level, developed in close collaboration with NVIDIA.

The goal is not elegance in simulation. It is confidence in outcomes.

Designing to an SLA

Every data center is built to meet a set of service-level agreements, whether explicit or implied. Historically, uncertainty in design data forced engineers to pad those designs with large safety margins.

That padding shows up as overbuilt power systems, oversized cooling, and higher costs.

Ikemoto argues that GPU-dense environments are making that approach untenable. When racks move from 10–20 kW to 50–100 kW (and toward a future that could reach megawatt-class racks) guesswork becomes expensive and dangerous.

Simulation, paired with validated DC elements, allows designers to model directly to an SLA: uptime targets, thermal limits, power availability, and cost-performance thresholds. The more precise the input data, the smaller the required design margin.

In other words, better models let operators spend less money to get more reliability.

What “Behaviorally Accurate” Really Means

Calling a model “accurate” is easy. Proving it is harder.

Cadence validates every DC element against supplier data, using a star system that reflects depth of detail and level of verification. Five-star elements undergo the strictest validation and require supplier approval.

For extreme-density systems like GB200, that means validating not just steady-state power and thermal behavior, but how those systems respond dynamically—under load changes, partial failures, and localized stress.

That level of fidelity is what allows simulation to move from illustrative to operational.

The Real Bottleneck: Knowledge

When asked about the biggest bottleneck in AI data center buildouts, Ikemoto does not point first to utilities, transformers, or chillers. He points to knowledge.

The industry is moving from a world of gradual IT evolution to one of discontinuous jumps. Power density has multiplied in just a few years. Cooling has shifted from mostly air to increasingly liquid. Interactions between systems have become tighter and more fragile.

Traditional design tools and rules of thumb evolved for a slower world. They struggle to keep up with this rate of change.

Physical prototyping is too slow and too expensive to fill the gap. Virtual prototyping, i.e. simulation, offers a way to build that knowledge faster, safer, and at lower cost. Ikemoto compares the moment to what aerospace and automotive industries went through decades ago, when simulation became the backbone of design.

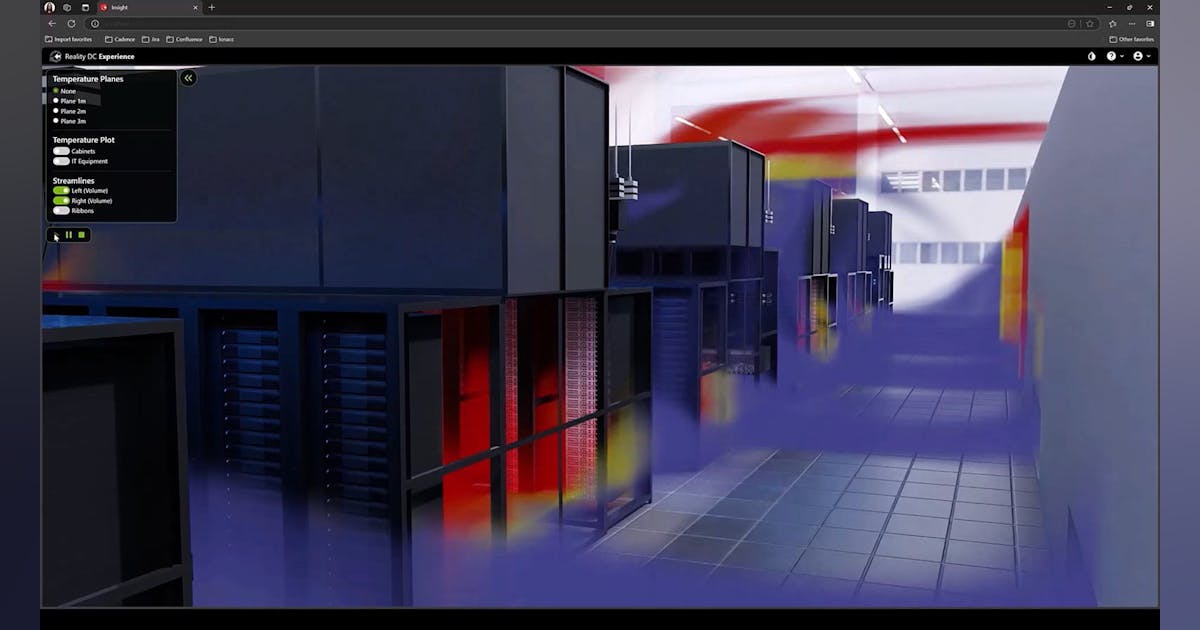

From CFD to a Digital Twin

Computational Fluid Dynamics has long been used in data centers to study airflow and heat transfer. But traditional CFD tools are slow, fragile, and built for general-purpose engineering, not for the specific realities of data centers.

Cadence’s Reality Digital Twin platform includes a custom CFD engine designed specifically for data center environments. It is optimized for airflow, liquid cooling, and hybrid systems, and built to run fast and reliably.

More importantly, it is embedded in a broader platform that supports design, commissioning, and operations. It can simulate next-generation AI factory architectures that mix air and liquid cooling, and critically, show how those systems interact.

That interaction is where many modern failures hide.

Extreme Co-Design and Omniverse

AI factories are too complex for power, cooling, IT layout, and operations to be designed in isolation. Changes in one domain ripple into the others.

NVIDIA calls this “extreme co-design”: designing all major systems together, continuously, to avoid late-stage conflicts.

Cadence is embedding NVIDIA Omniverse capabilities into its digital twin platform to support that approach. The vision is a shared simulation environment where different design tools exchange data in real time, conflicts are caught early, and optimization happens across domains, not in silos.

Looking further out, Ikemoto describes NVIDIA’s long-term vision of the AI factory as a largely autonomous system: robots installing, maintaining, and upgrading infrastructure, guided by a digital twin that acts as the factory’s operating system.

In that future, the digital twin is not just a design tool. It is the control layer for a living system.

The Twin After Day One

Too many digital twins stop at commissioning. Cadence’s Reality platform is designed to carry forward into operations.

Ikemoto says more than 2.5 million square feet of data center space (or nearly 700 data halls globally) already use digital twins operationally.

A model that begins in design becomes, after commissioning, a virtual replica of a specific physical facility. Connected to live monitoring systems, it can simulate future changes before they happen: IT upgrades, maintenance work, power reconfiguration.

Operators can test decisions in the twin before risking them in steel and silicon. The same visual model can be used to train people and eventually robots who will operate those facilities.

The shift is from digital twin as project artifact to digital twin as operational platform.

What Real AI Workloads Reveal

One of the most revealing parts of the conversation centers on what happens when real AI and machine-learning traces are run through simulation.

Some workloads create short, sharp bursts of power demand in localized areas. To be safe, many facilities provision power 20–30% above what they usually need, just to cover those spikes.

Most of that extra capacity sits unused most of the time. In an era where power is the primary bottleneck for AI factories, that waste matters.

By linking application behavior to hardware power profiles and then to facility-level power distribution, simulation can help smooth those spikes and reduce overprovisioning. It ties software design, IT design, and facility design into a single performance conversation.

That integration is where cost performance now lives.

Billion-Cycle Power Analysis

The conversation also touches on Cadence’s new Palladium Dynamic Power Analysis App, which can analyze billion-gate designs across billions of cycles with up to 97% accuracy.

What made that possible, Ikemoto says, is a combination of advances in emulation hardware and new algorithms that allow massive workloads to be profiled at realistic scale.

For data centers, the significance is indirect but profound. Better chip-level power modeling feeds better system-level models, which feed better facility-level designs.

The data center is, in Ikemoto’s words, “the ultimate system”: the place where all these components finally meet.

A Collaboration That Keeps Expanding

Cadence and NVIDIA have worked together for decades, with NVIDIA long relying on Cadence tools to design its chips.

What has changed is the scope of that collaboration. As accelerated computing reshapes infrastructure, their shared work has expanded from chips to systems to entire data centers.

The partnership now stretches from silicon to server to rack to AI factory. The common thread is simulation as a way to manage complexity before it becomes expensive.

Ikemoto frames it as a response to the digital transformation of the world. As more of life depends on compute, the infrastructure behind that compute has to be designed with the same rigor as the chips inside it.

The AI factory is not a metaphor anymore. It is an industrial system and like any industrial system, it needs blueprints that reflect reality.