A year ago, Norway became the first country to back deep sea mineral prospecting in its waters, with a government plan to launch an exploration licenses bidding round this year (2025).

Barely 11 months later, last December, the Norwegians suspended activity indefinitely, having been sued by a non-governmental organisation (NGO) – the widely respected Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF).

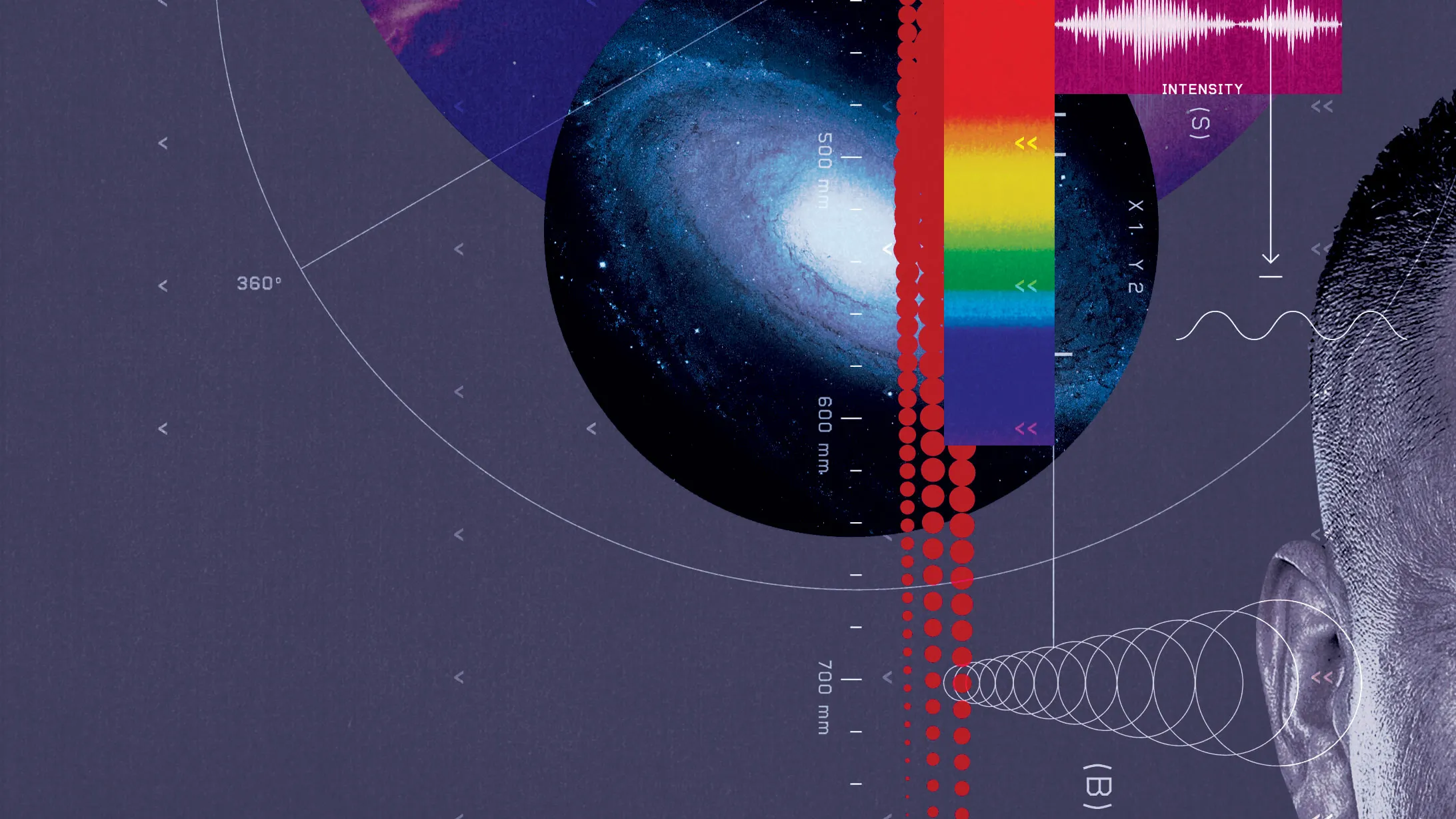

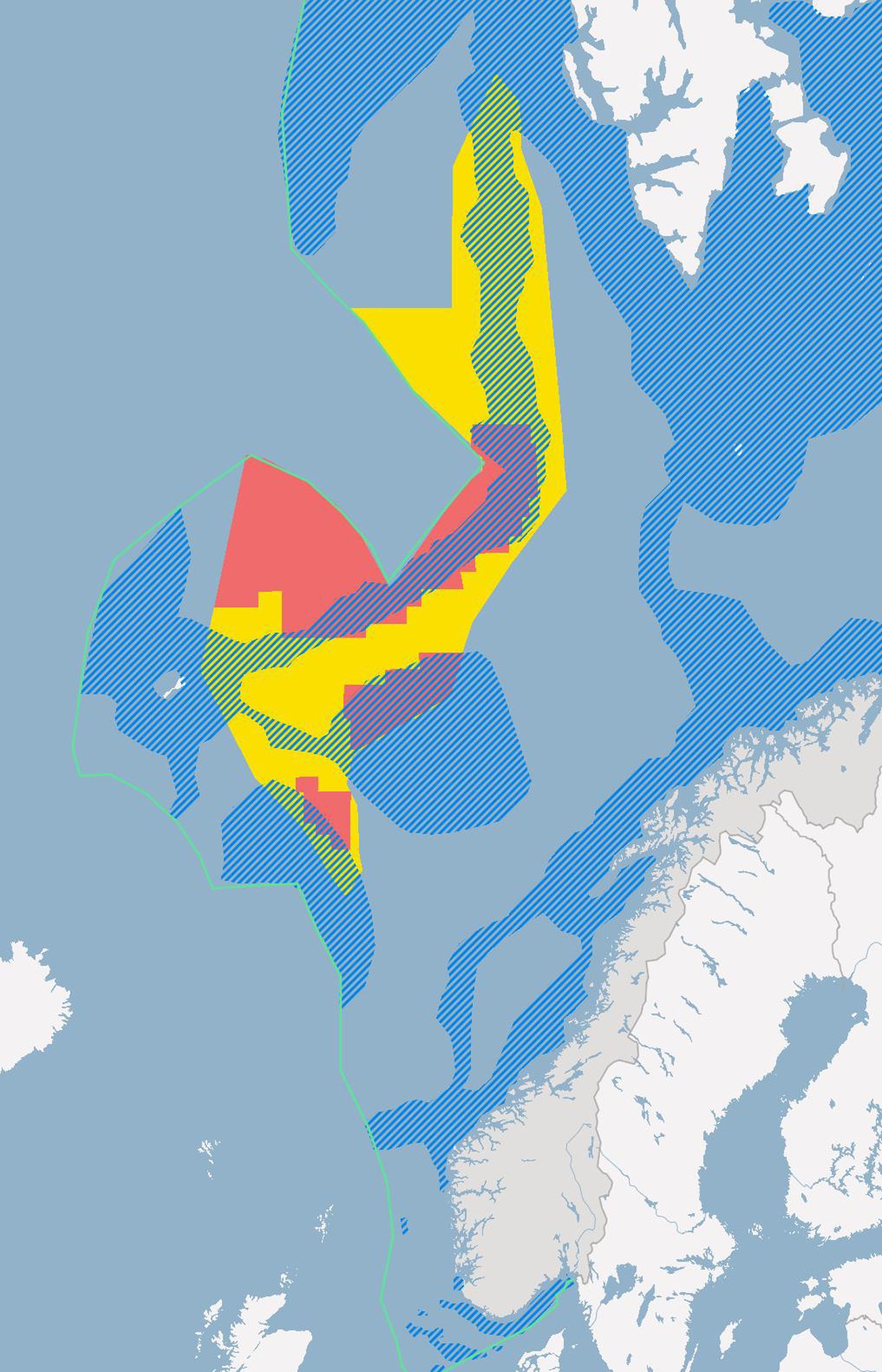

It was January 2024 when the Storting (Norwegian parliament) voted in favour of opening about 280,000 sq. km (108,000 square miles) of sea space between Jan Mayen island and the Svalbard archipelago for seabed minerals exploration.

It argued that the world needed minerals for the green transition, and that it was necessary to explore the possibility of extracting seabed minerals in a big way from the Norwegian Continental Shelf.

Despite the size of the prospective prize, minor political party SV (Socialist Left) tabled a demand that the Oslo government scrap its first licensing round, comprising 386 blocks, in return for support for the budget for 2025, which is also an election year.

Clearly spooked, Prime Minster Jonas Gahr Stoere claimed it was a “postponement”.

But even before the Storting’s January vote, Norway’s PM had come under pressure from the EU.

On November 9 2023, 119 European parliamentarians from 16 European countries called for a halt to Norway’s plans to start deep sea mining in the Arctic. This will have been viewed as deeply hurtful at the Oslo Parliament.

An open letter was issued, signed by Members of the European Parliament, as well as national and regional parliaments.

It emphasised that the green transition could not be used to justify harming marine biodiversity and the world’s largest natural carbon sink (the ocean), especially when alternatives already exist.

Norway’s decision to proceed with deep sea mining, the letter said, could also set a dangerous precedent in international waters.

© Supplied by WWF

© Supplied by WWFThis move forward, without a comprehensive international legal framework for deep sea mining, could open doors to similar ventures in other parts of the world, posing a risk to global ocean biodiversity.

WWF-Norway chief executive Karoline Andaur described the suspension as “a major and important environmental victory”.

However, a potentially major problem for Stoere is that parliamentary elections are due in September.

According to Norwegian media, the Conservative and Progress parties leading in the polls are in favour of deep sea mining.

The blocking by the SV party “has given the next Storting a chance to halt the hasty process,” according to Andaur.

A court decision was expected last month but no determination was evident at the time of going to press.

WWF’s court action was launched in May and is based on the impact assessment that the Stoere Administration used to guide decision making – which, by its own admission, contained scant information to help evaluate the potential impact of Arctic seafloor mining on the marine environment.

This mean that, for 99% of the area intended for offer to marine minerals prospectors, there is zero available environmental data.

But there is an estimate of the prize out there.

Two years ago, the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate on behalf of the country’s Ministry of Petroleum and Energy (MPE) published an assessment.

The Norwegian Continental Shelf survey identified “substantial” (millions of tonnes) of metals and minerals resources, ranging from copper to rare earth metals.

The list of ‘in-place’ reserve estimates includes:

- 38 million tonnes of copper

- 45 million tonnes of zinc

- 2,317 tonnes of gold

- 85,000 tonnes of silver

- 4.1 million tonnes of cobalt

- 230,000 tonnes of lithium

- 24 million tonnes of magnesium

- 8.4 million tonnes of titanium

- 1.9 million tonnes of vanadium

- 185 million tonnes of manganese

It happens that, of the metals found on the seabed in the study area, magnesium, niobium, cobalt and rare earth minerals are found on the European Commission’s list of critical minerals.

The WWF has accumulated significant knowledge of proposals around the world to establish an industry to mine minerals from deep ocean seafloors, typically resources such as manganese nodules.

Since 2019, the organisation has worked to ensure a global moratorium on deep seabed mining. Such a moratorium is considered necessary, at least until there is enough science available to make informed decisions about whether to go ahead with this allegedly destructive industry.

Without doubt, 2024 was a frustrating year for Norway as it sought to establish a lead in the seafloor minerals harvesting dash, claiming the energy transition as justification for wanting to be first out of the exploration gate.

On the one hand, research by a team of academics at Exeter University (published in the scientific journal Nature Sustainability in April) came down against deep sea mining.

On the other, the assessment A Deadly Moratorium by the Critical Ocean Mineral Research Center (COMRC) launched mid-October is deeply critical of WWF’s campaign against deep sea resources exploitation.

© Supplied by NCS

© Supplied by NCSThe Exeter report

The Exeter scientists want a blanket worldwide moratorium, insisting the controversial emerging industry currently poses an “unjustifiable environmental risk”.

They insist that the arguments put forward for deep sea mining fail to hold true from both an environmental and economic geology perspective.

They state in a summary: “Crucially, there is currently no coherent ‘net-zero carbon’ argument for the practice because the metals which deep sea mining could potentially source – including copper, nickel and cobalt, which are urgently needed to build renewable energy technology and thereby help decarbonise our society – remain widespread on land.”

They warn too: “Whilst on-land mining is also, by definition, environmentally destructive it is a relatively mature ‘tried and tested’ technology. In contrast, deep sea mining is highly novel and the environmental risk of such activity therefore remains largely unknown and could be extremely severe – and irreversible on human timescales.”

They point to an urgent need to scale up current on-land mining to source metals needed to tackle the Climate Emergency, and then ultimately be displaced with a fully circular ‘recycle and reuse’ economy.

Exeter co-author Dr Kate Littler warned: “The deep sea is the largest biome on Earth, home to unique and vulnerable organisms, many of which are still unknown to science.

“Human activity continues to severely disturb the biology and biogeochemistry of the global ocean through fishing, shipping and pollution; it is imperative we take the upmost care before deciding to decimate the deep sea for transient economic returns.”

Exeter’s Professor James Scourse, who is closely involved in the so-called Convex Seascape Survey – an ambitious five-year project examining ocean carbon storage – said: “If allowed to go ahead, deep sea mining would potentially result in global impacts that transcend national jurisdictions.

“For once, we have an opportunity to prevent catastrophic exploitation and to support responsible onshore mining to the benefit of local communities.”

The COMRC report

Turning to A Deadly Moratorium, amorphous, multi-stakeholder-owned COMRC is unequivocal in its condemnation of WWF’s efforts to put an end to deep sea mineral mining before it has even started.

COMRC claims the moratorium push is forcing countries and mining corporations to double down on some of the deadliest mineral extraction practices known, in the most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet, directly adjacent to human settlements.

It is apparently bringing death, disease and displacement to many vulnerable indigenous people each year that could be avoided. It is also impeding efforts to decarbonise while increasing greenhouse gas emissions.

Other claims laid include:

- Increased threat to Western national security and strategic industries – China dominates the world’s production and processing of critical minerals and has introduced restrictions on these minerals nine times from 2009-2020 (Coyne, 2024).

- Reduction in opportunity for breakthrough medical therapies – investment in nodule exploration has driven increased access to deep sea biological data, creating the opportunity for medical breakthroughs. Yet, the moratorium is claimed to impede this research by cutting off industry funding.

Basically, A Deadly Moratorium is a call for signatories to the moratorium to “reconsider their stance in the name of a more just energy transition and a healthier planet.”

COMRC claims too that several environmental NGOs have disclosed that they are in favour of careful nodule collection.

“While most of these groups are reluctant to publish anything that would undermine the fundraising campaigns of big, corporate NGOs such as WWF and Greenpeace, at least one, The Breakthrough Institute, has already broken ranks (Wang, 2024).

“We know that others have followed, and we are confident that more will come along as they critically analyse the scientific research and the data.”

Meanwhile, the UN’s International Seabed Authority (ISA), which oversees areas of the marine floor that do not belong to national territories, has been working on rules for deep sea mining for years. But they are not yet complete.

The ISA has, to date, granted exploration licenses in various deep sea regions, including in the Pacific Ocean. Some countries such as China, Japan and Russia would like to start mining the seabed as soon as possible.

However, according to the WWF, 32 other states are now calling for a precautionary pause or a moratorium on deep sea mining to allow for more research.

And it has also been claimed that more than 50 international companies, including Apple, Google, Microsoft and BMW, have stated they will not source components from deep sea mining minerals. They are publicly listed by WWF.

ISA told Energy Voice: “A total of 31 exploration contracts have been issued to 22 contractors.

“In December 2021, CPRM (The Geological Survey Brazil) renounced its rights in relation to its exploration contract.

“As of today, the number of contracts in effect is 30 with 21 contractors.”

In the case of CPRM, its contract covered polymetallic nodules, polymetallic sulphides, and cobalt-rich crusts in the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone, Central Indian Ocean Basin and Western Pacific Ocean.

It has taken decades for deep sea mining to get this far – and the pace seems unlikely to quicken anytime soon.

Recommended for you

Norway shelves plans for deep sea mining until at least 2026