In a previous Energy Voice article, Isla Robb – from a private economic development agency in Aberdeen – argues that a Scottish and/or English manufacturing facility from Mingyang, the Chinese wind turbine manufacturer, should be welcomed.

I have previously outlined why Chinese investment in the UK wind industry should be treated with extreme caution.

Not least of the reasons are extensive concerns from the most senior figures in the UK defence establishment.

This is hardly surprising given China’s support for Russia against Ukraine in Europe’s first major hot conflict since World War II or given credible reports of Chinese espionage and/or sabotage against critical European infrastructure.

If, post Brexit, we still care about Europe, we might also consider last year’s decision by Brussels to initiate investigations into Chinese wind turbines under the new Foreign Subsidies Regulation.

However, let us ignore those concerns and focus solely on the supply chain. As the article notes, a deficit of domestic manufacturing, despite our world-class wind resource, has long been a sore point.

The reason is not because of a perceived malevolent oligopoly of the three existing US and European turbine manufacturers. It is rather the UK policy mechanism used to support renewables: the contract for difference (CfD).

It has done a fantastic job in reducing the cost of offshore wind energy but a poor one of encouraging long-term investment in domestic manufacturing.

This is why the UK has such a weak record of creating in-country wind jobs. Since the problem is the CfD, the solution is most certainly not China.

China’s track record

The second flaw in the argument concerns jobs in Scotland, the wider UK and, indeed, Europe. It says almost nothing about the most important issue of all: how Mingyang will leverage our best-in-Europe wind resource to create supply chain jobs in the UK for British companies.

Given the lack of information, let us instead consider China’s track record. Their many ‘Belt and Road’ initiatives provide ample evidence that their goal is, first and foremost, to create jobs for China and to dominate capital-intensive, global industries such as steel, glass, paper, auto parts, solar, wind energy and more.

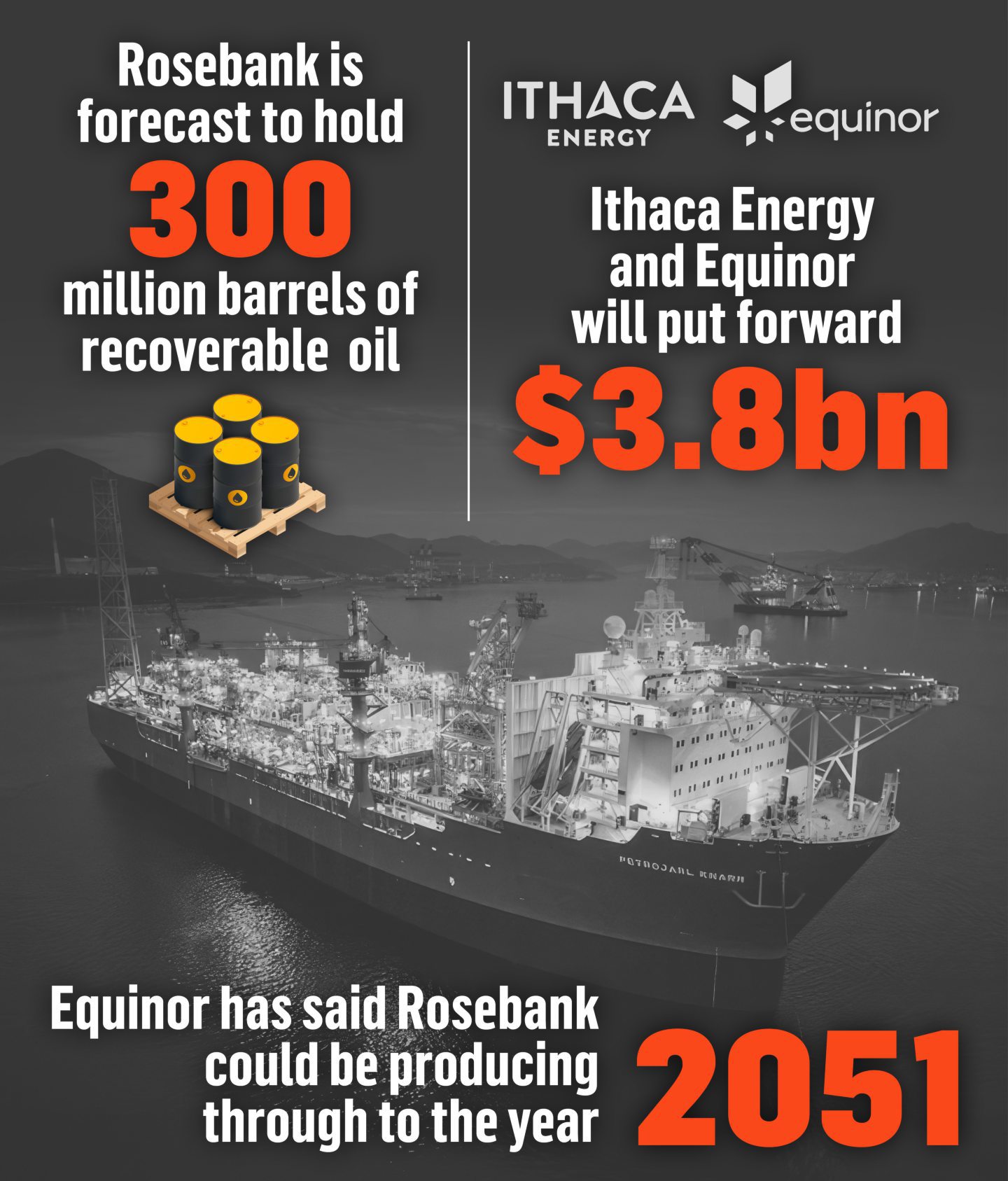

Consider solar: Europe created and led the global solar PV industry until 2011 when it employed 330,000 Europeans and at which point China decided it wanted control.

© Supplied by James Glennie

© Supplied by James GlennieOver the next 6 years, European solar lost 240,000 jobs – or 73% of its total 2011 workforce – to China.

For comparison, this is equivalent to 60% of the 425,000 people that currently work in Europe’s oil industry.

Today, China is responsible for 85-97% (depending on which segment one considers) of global solar manufacturing and employs 2 million people in the sector representing 52% of the global solar workforce.

As The Economist noted in June, “The fact that a vital industry resides in a single hostile country is worrying.”

To bolster this phenomenal growth in solar, and in other critical industries, China has stolen – and continues to steal – vast amounts of IP and western technology.

It has, as noted, also employed massive state subsidies to support its domestic industries in addition to encouraging labour and environmental standards which would simply be unacceptable in Western Europe. That is its choice as an emerging power.

It is nonetheless important that, if the UK is not to cede another critical industry to China, it enters into any new relationship – such as Mingyang’s UK proposal – with its eyes wide open as to what this means for jobs, IP and economic development in the long term.

Given the incentives of the CfD, Scottish Renewables – the Scottish offshore wind lobby group – cannot be faulted for supporting Mingyang’s bid.

However, the Scottish Development Agencies (SE & HIE) should be asking tough questions about what such an investment will mean, in the long-term, for Scottish economic development, jobs, R&D, universities and IP retention.

Alternatives

The neoliberal, democratic agenda of the last 80 years has undoubtedly created enormous wealth. However, it is hard to argue with the notion that today’s right-wing political ructions – most notably emanating from Trump’s America but now spreading to France, Germany, Italy and others – are a direct reaction to how that wealth has been distributed and the lack of job security for blue-collar workers.

Given this, and the failure of the European solar industry less than a decade ago, it is incumbent on decision makers to see the threat posed by Mingyang’s proposal.

By accepting a relatively small amount of capital from a hostile foreign power with a track record of stealing IP and offshoring jobs to China, Scotland/UK would be giving up much of the employment and economic potential inherent in its possession of the world’s best offshore wind resource.

By putting at risk the livelihoods of the 285,000 people that currently work in the European wind sector, Britain would also be turning its back firmly on Europe – where two of the world’s leading wind turbine manufacturers are based.

Is there an alternative? Of course there is. The aforementioned wind turbine manufacturers – Siemens Gamesa and Vestas – are located in countries which border the North Sea.

We share with them a common culture and ethics as well as employment and environmental laws. Those companies created the modern wind industry, are transparent and have a proven track record.

This European solution would require some tough negotiations coupled with a critical review of the CfD. However, and backed by our staggering offshore wind pipeline of 45 GW+, there is every reason to be believe it is eminently achievable and that, once done, it will be vastly better for Scottish economic interests, for the Scottish offshore wind industry and for our relations with the rest of Europe.

Britain’s electrification plans are at serious risk of stumbling unless we reboot Britain’s industrial capacity for the long term and that means a trained workforce.

The Mingyang decision is therefore not one which should be rushed through to meet short-term profit mandates of a few wind developers or the immediate political needs of politicians with an eye to the next election.

Outsourcing of critical manufacturing to a hostile country will only further entrench the economic malaise which has caused UK per capita GDP – currently $53,700 – to stagnate since 2017 and to now equal that of America’s poorest state: Mississippi ($53,100).

We should choose carefully the partners that will be responsible for monetising our bountiful wind resource. If we do can do that, future generations will thank us for a creating a national treasure that will last far longer than the rapidly fading North Sea oil & gas industry.

Recommended for you

UK government urged to ‘make a decision’ quickly on zonal pricing