Jane Muschenetz’s poems don’t look like the sonnets you remember studying in high school English. If anything, they’re more likely to call to mind your statistics class.

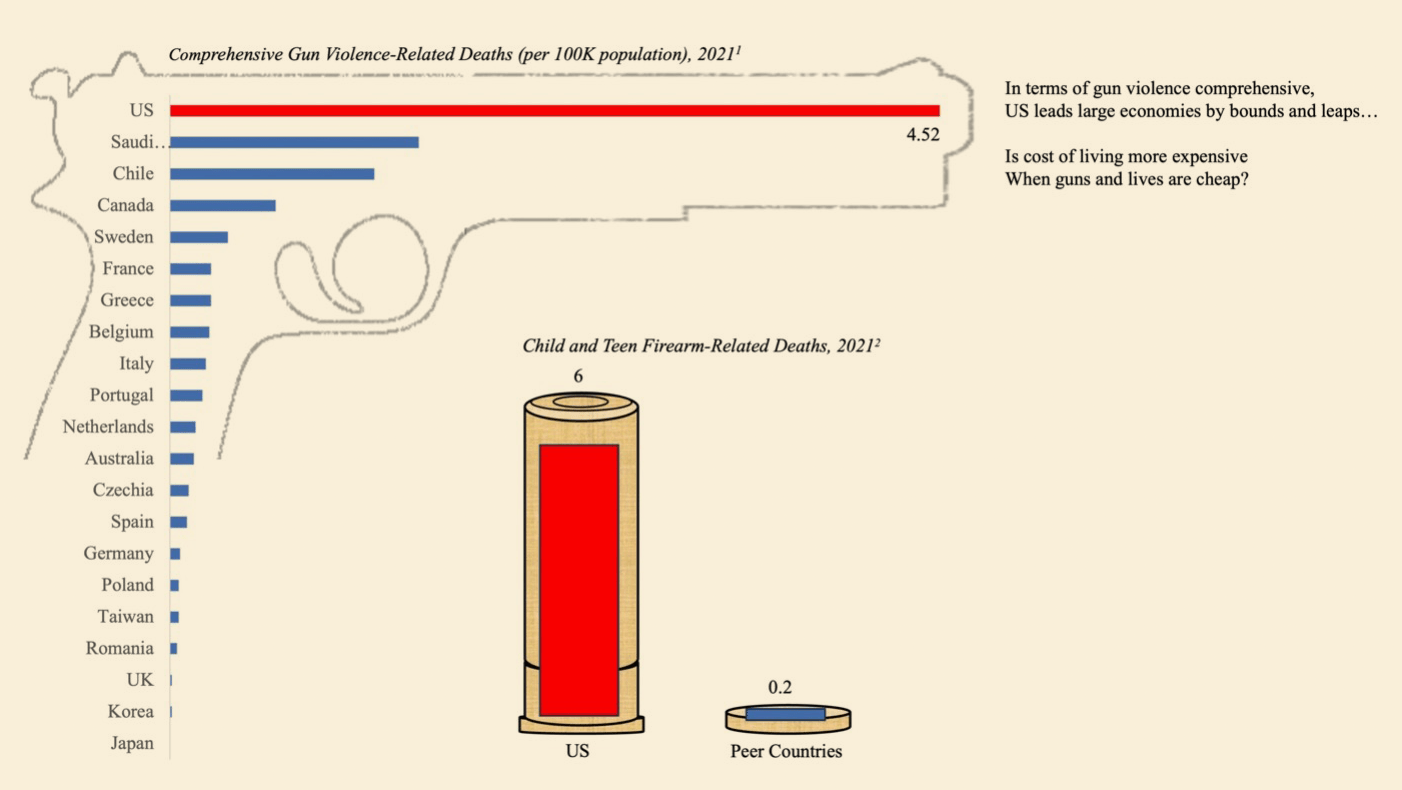

Flip through the pages of her poetry chapbook Power Point and you’ll see charts, graphs, and citations galore. One poem visually documents maternal mortality rates and women’s unpaid domestic labor in such a way that the bar and pie graphs spell out the word “MOM.” Another tracks deaths from gun violence across the globe and is presented as a gun-shaped graph. Still others are written in more standard poetic form but include citations that reference documents put out by the US government, the United Nations, and news organizations.

These poems are just a few of the many in Muschenetz’s latest book that wrestle with contemporary social issues using a combination of data-driven insights and the poetic form. The format is a unique one: The first time Hayley Mitchell Haugen, founding editor in chief of Muschenetz’s publisher Sheila-Na-Gig, saw the poems, she thought to herself, “I’ve never seen anything like this before.”

Point Blank

While cold, hard numbers and poetry might seem antithetical at first blush, from Muschenetz’s perspective, the two couldn’t be a better fit. A former business consultant at Bain & Company who received her MBA at the Sloan School of Management, she released her first poetry book in her 40s, and she’s enjoyed uncovering what the artistic and scientific approaches to understanding the world have in common.

“Even though it maybe feels unintuitive that poetry and science are interrelated, they both make connections that are not immediately obvious,” she says. “They test out theories; they take risks. There’s a lot of nonlinear thinking that happens in both.”

Many of the poems in Power Point were inspired by watershed moments in global politics and culture, particularly ones that would shape the lives of women. From the partisan political theater on display at the confirmation hearing of US Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson to the passage of laws restricting women’s freedoms in Iran and Afghanistan, these events often left Muschenetz overwhelmed with frustration at the state of women’s rights today.

But knowing that women’s emotions are so often dismissed, she looked for a way to turn those feelings into something that she hoped would be harder to write off than standard poetry while still evoking the openheartedness with which people tend to approach art.

“I wanted something that listed just facts but expressed how angry I am,” she says. “I really wanted it to be fact-based. I wanted my sources to be publicly available and almost unassailable.” Her hope was that by repackaging these facts in the form of statistics-driven poetry, she might allow readers to receive the information in a new way—and get them thinking.

From Ukraine to California

Muschenetz’s childhood primed her to understand how global currents can shape an individual life from an early age. Born Yevgenia Leonidovna Veitzman to a Jewish family in the Ukrainian city of Lviv, Muschenetz says her family began trying to leave the country before she was born, hoping to escape the discrimination they faced under the Soviet government. But it wasn’t until she was 10 years old that the family was finally able to emigrate. When they were at last cleared to cross the border, they headed for San Diego, where she decided that Jane would be easier for Americans to pronounce than her given first name. (Ultimately, she would change her last name, too, when she married.)

Muschenetz often felt out of place in her new home, even though she was surrounded by other immigrant kids whose parents had moved to California in search of a better life. In one way she was like many American teenage girls, though: She had a lot of feelings, especially about romantic relationships, whether real or imagined, and she often wrote poems about them.

At age 16, she began submitting her poetry to magazines and publishers, which brought her first taste of writerly rejection. “I was like, ‘Oh, well, I tried. Clearly this isn’t for me.’ Even though in my heart, since I was like four years old, I knew I was a writer and I loved literature,” she says.

Her parents were “completely horrified” about the prospect of her pursuing a career in writing, but they weren’t much more excited about what she eventually landed on instead: a degree in political science at UC San Diego. “The response was always ‘Poets get shot. Politicians get shot,’” she says.

She might not have been able to articulate it at age 18, but looking back, Muschenetz makes sense of the decision to study political science as driven by her desire to understand the global forces that caused her family to emigrate. “I wanted to know: How do we structure policy? Who makes these choices, and how can we change them and make them better?” she says.

But the dream of writing was hard to let go of. By the time Muschenetz was a few years out of college, she’d applied for two different programs: an MFA in writing and the MBA program at Sloan. And though she didn’t get accepted to the MFA program, her time at Sloan ended up profoundly shaping the poetry she would write two decades later, giving her the statistical analysis and data interpretation skills that formed the backdrop for Power Point. Those were skills she sharpened even further in the years she spent working as a business consultant at Bain right after earning her MBA.

“I don’t think the average joe could pull off [what she does in that book], because she knows how to present statistics well,” says Haugen. “She knows how to look at them analytically and offer them up in a way that a layperson can understand.”

Muschenetz left the business world after four years at Bain to focus on parenting her two children, as well as serving in various volunteer capacities at their schools and with local community organizations. It wasn’t until the world shut down in 2020 with the onset of the covid-19 pandemic that she found herself getting back in touch with the creative impulses that had animated her previously. Those impulses manifested in part as visual art: Muschenetz began painting a menagerie of animals on the bases of palm fronds she would find on the ground after a big storm in San Diego. “It just felt good, even though it made no sense,” she says. “At the same time, it was keeping me sane.”

Being willing to dip her toe into a creative endeavor that she knew she “didn’t have to be good at” also helped open Muschenetz to the idea of getting back to the poetry writing that had made her heart sing as a girl.

“Through my high school and early college years, every margin of every notebook was covered with poems or rhymes,” she says. “And then it was just gone. It was scary for me to realize that I had cut that part out of myself, and how bad that was for me.”

Coming home to poetry

When Muschenetz did start writing again, she thought she might write a collection of poems rooted in domesticity and home life. She was surprised to find that what started flowing out of her instead were poems about her immigrant experience, which had never been the subject of her poetry while she was living it as a teenager. “I thought, ‘Well, shouldn’t I have gotten this out of my system?’ But here I was writing about this aspect of my identity that I never actually had written about before.”

She eventually had enough poems to pull together what became her first collection, titled All the Bad Girls Wear Russian Accents. The book reveals her propensity for weaving together dark and light, humor and tragedy, in a range of poems that cover everything from the war in Ukraine to the experience of being stereotyped for her ability to speak Russian, the language of many American movie villains.

Muschenetz initially thought that writing a book of poetry might be a onetime thing, the kind of undertaking that would allow her to check a box and move on. But as she was promoting her first book, she found herself fixating on a poem she hadn’t even written yet—one in the form of data that would spell out a word. The idea was eventually realized in “100% MOM.”

100% MOM: A PowerPoint Poem about Women and Labor

That poem was the seed that grew into Power Point, and Muschenetz, whose poetry has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize three times, hasn’t looked back since. In addition to releasing that second volume of poetry, the product of what she calls the “analytic and overachieving brain” that helped her get through (and enjoy) business school, Muschenetz has used those same skills to help the poetry community in San Diego with some of the more practical needs, like grant writing, that are often lacking in communities of artists, says Katie Manning, a local poet and professor emeritus of poetry.

Muschenetz is mostly just happy to have found a way to use poetry to keep integrating and honoring the many different parts of her identity, from immigrant to business consultant.

“It is a huge disservice to all humanity when we ask our scientists or mathematicians or poets to only be that one thing, as opposed to being their whole selves,” she says.

You Are 600% Hotter than the Sun

By Jane Muschenetz

A cup of the Sun’s core produces ~60 milliwatts

of thermal energy. By volume … less than that of

a human [350 mW]. In a sense, you are hotter than

the Sun—there’s just not as much of you.

—Henry Reich, Minute Physics

Speaking roughly, in terms of heat

generated per every human inch, you give

off more milliwatts—surge/energy. Only

the Sun is bigger … it matters.

We are all blinded

by love, the expanding/contracting

universe is just another metaphor

for longing, and life—its own purpose.

How dazzling, this science!

Consider falling for a physicist—

the painstakingly slow way they undress

mathematical mysteries,

talk about bodies in motion

gets me every time—space

—continuum, part, particle—

Atomic. Incandescent! You

are, pound-for-pound, more Life-Source,

more Bomb, more Season-Spinning Searing Center

Heart/Engine/Radiating Nuclear Dynamic

than the Sun. Can’t look directly

in the mirror? Small Wonder! Imagine—

none of us powerless.

Originally published by Cathexis Northwest Press, May 2024

For Those of Us Forced to Flee

By Jane Muschenetz

For those of us forced to flee

the world is forever shrinking down to a single question:

What can you carry?

The suitcase of your heart closed tight

on all the things there was no room to bring—

your memories of “home,” the snowflake moments

of your youth, the blooming Lilac tree

outside your bedroom window … a heavy burden

saps your strength on the long journey, bring

only what you need.

Homes can be built again,

a new tree can be rooted.

Survive.

When you have nothing left to plant, become the seed.

Originally published in Issue 8, The Good Life Review, 2022. It received the 2022 Honeybee Poetry Prize and was nominated for a Pushcart Prize.

Find more poetry by Jane Muschenetz at www.palmfrondzoo.com/janewriting.