The Thwaites glacier is a fortress larger than Florida, a wall of ice that reaches nearly 4,000 feet above the bedrock of West Antarctica, guarding the low-lying ice sheet behind it.

But a strong, warm ocean current is weakening its foundations and accelerating its slide into the Amundsen Sea. Scientists fear the waters could topple the walls in the coming decades, kick-starting a runaway process that would crack up the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

That would mark the start of a global climate disaster. The glacier itself holds enough ice to raise ocean levels by more than two feet, which could flood coastlines and force tens of millions of people living in low-lying areas to abandon their homes.

The loss of the entire ice sheet—which could still take centuries to unfold—would push up sea levels by 11 feet and redraw the contours of the continents.

This is why Thwaites is known as the doomsday glacier—and why scientists are eager to understand just how likely such a collapse is, when it could happen, and if we have the power to stop it.

Scientists at MIT and Dartmouth College founded Arête Glacier Initiative last year in the hope of providing clearer answers to these questions. The nonprofit research organization will officially unveil itself, launch its website, and post requests for research proposals today, March 21, timed to coincide with the UN’s inaugural World Day for Glaciers, MIT Technology Review can report exclusively.

Arête will also announce it is issuing its first grants, each for around $200,000 over two years, to a pair of glacier researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

One of the organization’s main goals is to study the possibility of preventing the loss of giant glaciers, Thwaites in particular, by refreezing them to the bedrock. It would represent a radical intervention into the natural world, requiring a massive, expensive engineering project in a remote, treacherous environment.

But the hope is that such a mega-adaptation project could minimize the mass relocation of climate refugees, prevent much of the suffering and violence that would almost certainly accompany it, and help nations preserve trillions of dollars invested in high-rises, roads, homes, ports, and airports around the globe.

“About a million people are displaced per centimeter of sea-level rise,” says Brent Minchew, an associate professor of geophysics at MIT, who cofounded Arête Glacier Initiative and will serve as its chief scientist. “If we’re able to bring that down, even by a few centimeters, then we would safeguard the homes of millions.”

But some scientists believe the idea is an implausible, wildly expensive distraction, drawing money, expertise, time, and resources away from more essential polar research efforts.

“Sometimes we can get a little over-optimistic about what engineering can do,” says Twila Moon, deputy lead scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado Boulder.

“Two possible futures”

Minchew, who earned his PhD in geophysics at Caltech, says he was drawn to studying glaciers because they are rapidly transforming as the world warms, increasing the dangers of sea-level rise.

“But over the years, I became less content with simply telling a more dramatic story about how things were going and more open to asking the question of what can we do about it,” says Minchew, who will return to Caltech as a professor this summer.

Last March, he cofounded Arête Glacier Initiative with Colin Meyer, an assistant professor of engineering at Dartmouth, in the hope of funding and directing research to improve scientific understanding of two big questions: How big a risk does sea-level rise pose in the coming decades, and can we minimize that risk?

“Philanthropic funding is needed to address both of these challenges, because there’s no private-sector funding for this kind of research and government funding is minuscule,” says Mike Schroepfer, the former Meta chief technology officer turned climate philanthropist, who provided funding to Arête through his new organization, Outlier Projects.

The nonprofit has now raised about $5 million from Outlier and other donors, including the Navigation Fund, the Kissick Family Foundation, the Sky Foundation, the Wedner Family Foundation, and the Grantham Foundation.

Minchew says they named the organization Arête, mainly because it’s the sharp mountain ridge between two valleys, generally left behind when a glacier carves out the cirques on either side. It directs the movement of the glacier and is shaped by it.

It’s meant to symbolize “two possible futures,” he says. “One where we do something; one where we do nothing.”

Improving forecasts

The somewhat reassuring news is that, even with rising global temperatures, it may still take thousands of years for the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to completely melt.

In addition, sea-level rise forecasts for this century generally range from as little as 0.28 meters (11 inches) to 1.10 meters (about three and a half feet), according to the latest UN climate panel report. The latter only occurs under a scenario with very high greenhouse gas emissions (SSP5-8.5), which significantly exceeds the pathway the world is now on.

But there’s still a “low-likelihood” that ocean levels could surge nearly two meters (about six and a half feet) by 2100 that “cannot be excluded,” given “deep uncertainty linked to ice-sheet processes,” the report adds.

Two meters of sea-level rise could force nearly 190 million people to migrate away from the coasts, unless regions build dikes or other shoreline protections, according to some models. Many more people, mainly in the tropics, would face heightened flooding dangers.

Much of the uncertainty over what will happen this century comes down to scientists’ limited understanding of how Antarctic ice sheets will respond to growing climate pressures.

The initial goal of Arête Glacier Initiative is to help narrow the forecast ranges by improving our grasp of how Thwaites and other glaciers move, melt, and break apart.

Gravity is the driving force nudging glaciers along the bedrock and reshaping them as they flow. But many of the variables that determine how fast they slide lie at the base. That includes the type of sediment the river of ice slides along; the size of the boulders and outcroppings it contorts around; and the warmth and strength of the ocean waters that lap at its face.

In addition, heat rising from deep in the earth warms the ice closest to the ground, creating a lubricating layer of water that hastens the glacier’s slide. That acceleration, in turn, generates more frictional heat that melts still more of the ice, creating a self-reinforcing feedback effect.

Minchew and Meyer are confident that the glaciology field is at a point where it could speed up progress in sea-level rise forecasting, thanks largely to improving observational tools that are producing more and better data.

That includes a new generation of satellites orbiting the planet that can track the shifting shape of ice at the poles at far higher resolutions than in the recent past. Computer simulations of ice sheets, glaciers and sea ice are improving as well, thanks to growing computational resources and advancing machine learning techniques.

On March 21, Arête will issue a request for proposals from research teams to contribute to an effort to collect, organize, and openly publish existing observational glacier data. Much of that expensively gathered information is currently inaccessible to researchers around the world, Minchew says.

By funding teams working across these areas, Arête’s founders hope to help produce more refined ice-sheet models and narrower projections of sea-level rise.

This improved understanding would help cities plan where to build new bridges, buildings, and homes, and to determine whether they’ll need to erect higher seawalls or raise their roads, Meyer says. It could also provide communities with more advance notice of the coming dangers, allowing them to relocate people and infrastructure to safer places through an organized process known as managed retreat.

A radical intervention

But the improved forecasts might also tell us that Thwaites is closer to tumbling into the ocean than we think, underscoring the importance of considering more drastic measures.

One idea is to build berms or artificial islands to prop up fragile parts of glaciers, and to block the warm waters that rise from the deep ocean and melt them from below. Some researchers have also considered erecting giant, flexible curtains anchored to the seabed to achieve the latter effect.

Others have looked at scattering highly reflective beads or other materials across ice sheets, or pumping ocean water onto them in the hopes it would freeze during the winter and reinforce the headwalls of the glaciers.

But the concept of refreezing glaciers in place, know as a basal intervention, is gaining traction in scientific circles, in part because there’s a natural analogue for it.

The glacier that stalled

About 200 years ago, the Kamb Ice Stream, another glacier in West Antarctica that had been sliding about 350 meters (1,150 feet) per year, suddenly stalled.

Glaciologists believe an adjacent ice stream intersected with the catchment area under the glacier, providing a path for the water running below it to flow out along the edge instead. That loss of fluid likely slowed down the Kamb Ice Stream, reduced the heat produced through friction, and allowed water at the surface to refreeze.

The deceleration of the glacier sparked the idea that humans might be able to bring about that same phenomenon deliberately, perhaps by drilling a series of boreholes down to the bedrock and pumping up water from the bottom.

Minchew himself has focused on a variation he believes could avoid much of the power use and heavy operating machinery hassles of that approach: slipping long tubular devices, known as thermosyphons, down nearly to the bottom of the boreholes.

These passive heat exchangers, which are powered only by the temperature differential between two areas, are commonly used to keep permafrost cold around homes, buildings and pipelines in Arctic regions. The hope is that we could deploy extremely long ones, stretching up to two kilometers and encased in steel pipe, to draw warm temperatures away from the bottom of the glacier, allowing the water below to freeze.

Minchew says he’s in the process of producing refined calculations, but estimates that halting Thwaites could require drilling as many as 10,000 boreholes over a 100-square-kilometer area.

He readily acknowledges that would be a huge undertaking, but provides two points of comparison to put such a project into context: Melting the necessary ice to create those holes would require roughly the amount of energy all US domestic flights consume from jet fuel in about two and a half hours. Or, it would produce about the same level of greenhouse gas emissions as constructing 10 kilometers of seawalls, a small fraction of the length the world would need to build if it can’t slow down the collapse of the ice sheets, he says.

“Kick the system”

One of Arête’s initial grantees is Marianne Haseloff, an assistant professor of geoscience at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She studies the physical processes that govern the behavior of glaciers and is striving to more faithfully represent them in ice sheet models.

Haseloff says she will use those funds to develop mathematical methods that could more accurately determine what’s known as basal shear stress, or the resistance of the bed to sliding glaciers, based on satellite observations. That could help refine forecasts of how rapidly glaciers will slide into the ocean, in varying settings and climate conditions.

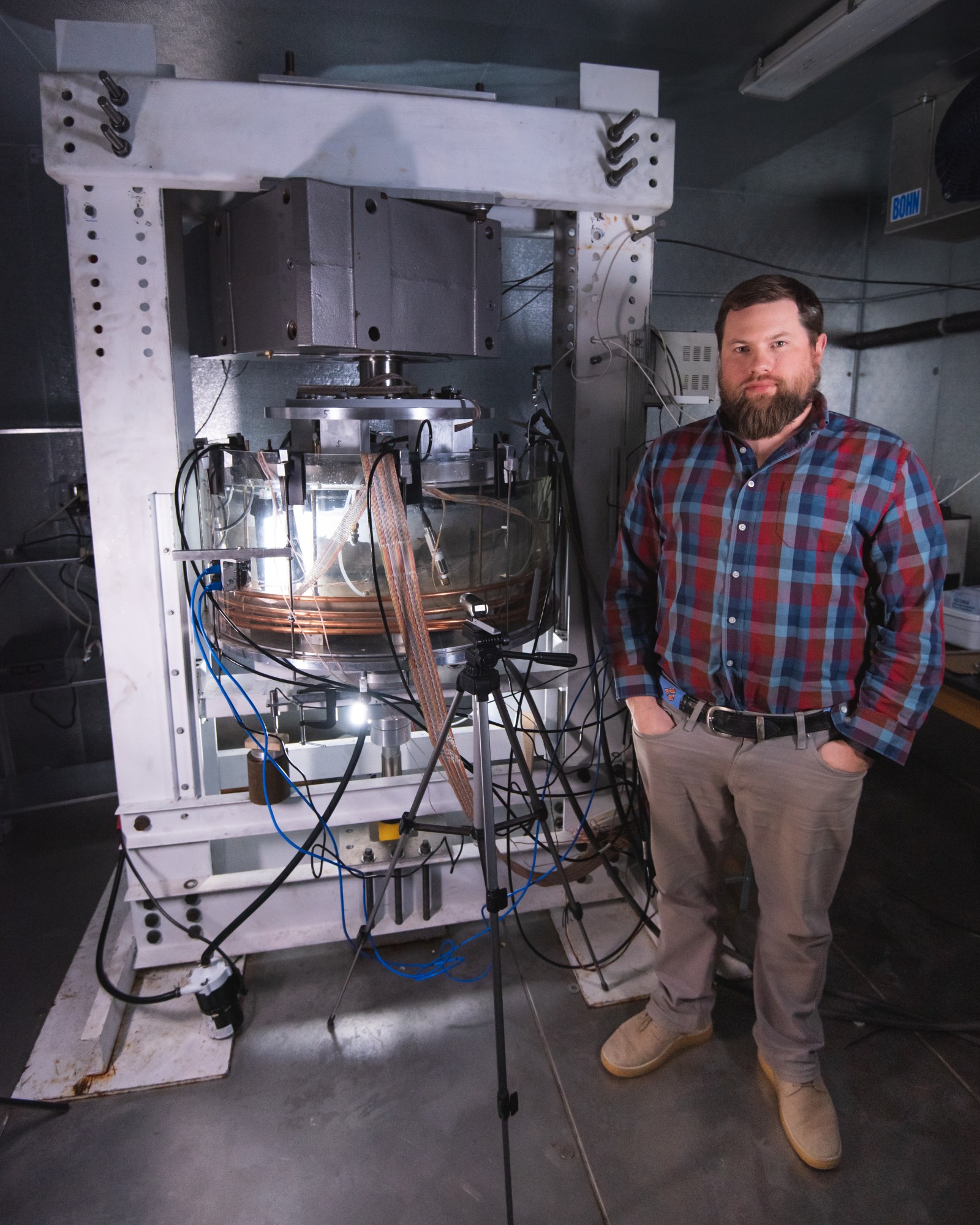

Arête’s other initial grant will go to Lucas Zoet, an associate professor in the same department as Haseloff and the principal investigator with the Surface Processes group.

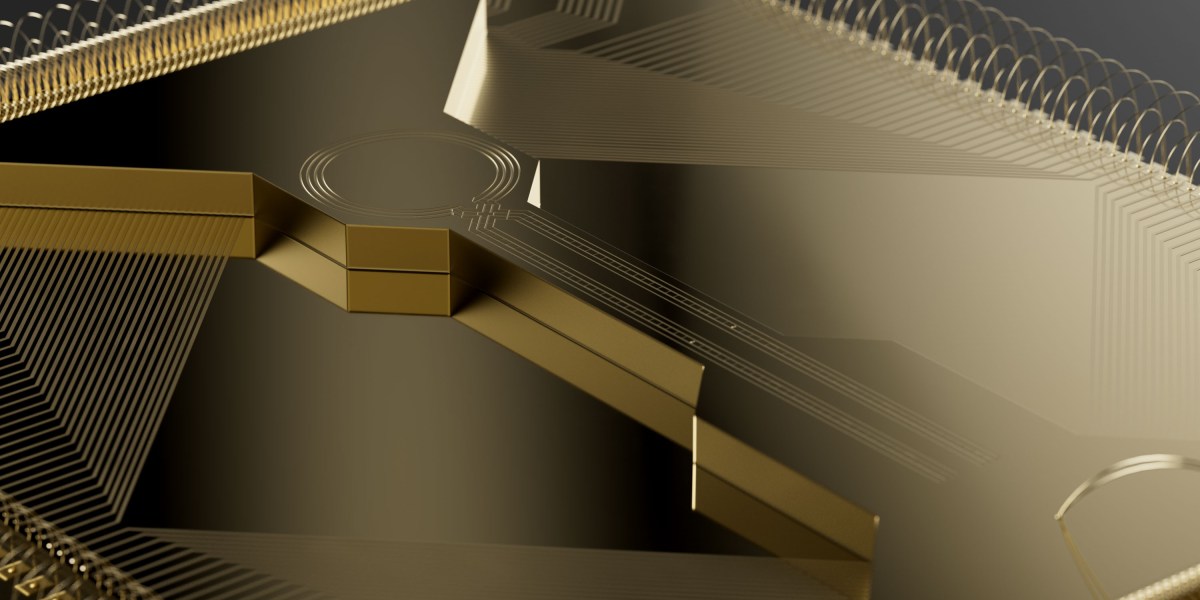

He intends to use the funds to build the lab’s second “ring shear” device, the technical term for a simulated glacier.

The existing device, which is the only one operating in the world, stands about eight feet tall and fills the better part of a walk-in freezer on campus. The core of the machine is a transparent drum filled with a ring of ice, sitting under pressure and atop a layer of sediment. It slowly spins for weeks at a time as sensors and cameras capture how the ice and earth move and deform.

The research team can select the sediment, topography, water pressure, temperature, and other conditions to match the environment of a real-world glacier of interest, be it Thwaites today—or Thwaites in 2100, under a high greenhouse gas emissions scenario.

Zoet says these experiments promise to improve our understanding of how glaciers move over different types of beds, and to refine an equation known as the slip law, which represents these glacier dynamics mathematically in computer models.

The second machine will enable them to run more experiments and to conduct a specific kind that the current device can’t: a scaled-down, controlled version of the basal intervention.

Zoet says the team will be able to drill tiny holes through the ice, then pump out water or transfer heat away from the bed. They can then observe whether the simulated glacier freezes to the base at those points and experiment with how many interventions, across how much space, are required to slow down its movement.

It offers a way to test out different varieties of the basal intervention that is far easier and cheaper than using water drills to bore to the bottom of an actual glacier in Antarctica, Zoet says. The funding will allow the lab to explore a wide range of experiments, enabling them to “kick the system in a way we wouldn’t have before,” he adds.

“Virtually impossible”

The concept of glacier interventions is in its infancy. There are still considerable unknowns and uncertainties, including how much it would cost, how arduous the undertaking would be, and which approach would be most likely to work, or if any of them are feasible.

“This is mostly a theoretical idea at this point,” says Katharine Ricke, an associate professor at the University of California, San Diego, who researches the international relations implications of geoengineering, among other topics.

Conducting extensive field trials or moving forward with full-scale interventions may also require surmounting complex legal questions, she says. Antarctica isn’t owned by any nation, but it’s the subject of competing territorial claims among a number of countries and governed under a decades-old treaty to which dozens are a party.

The basal intervention—refreezing the glacier to its bed—faces numerous technical hurdles that would make it “virtually impossible to execute,” Moon and dozens of other researchers argued in a recent preprint paper, “Safeguarding the polar regions from dangerous geoengineering.”

Among other critiques, they stress that subglacial water systems are complex, dynamic, and interconnected, making it highly difficult to precisely identify and drill down to all the points that would be necessary to remove enough water or add enough heat to substantially slow down a massive glacier.

Further, they argue that the interventions could harm polar ecosystems by adding contaminants, producing greenhouse gases, or altering the structure of the ice in ways that may even increase sea-level rise.

“Overwhelmingly, glacial and polar geoengineering ideas do not make sense to pursue, in terms of the finances, the governance challenges, the impacts,” and the possibility of making matters worse, Moon says.

“No easy path forward”

But Douglas MacAyeal, professor emeritus of glaciology at the University of Chicago, says the basal intervention would have the lightest environmental impact among the competing ideas. He adds that nature has already provided an example of it working, and that much of the needed drilling and pumping technology is already in use in the oil industry.

“I would say it’s the strongest approach at the starting gate,” he says, “but we don’t really know anything about it yet. The research still has to be done. It’s very cutting-edge.”

Minchew readily acknowledges that there are big challenges and significant unknowns—and that some of these ideas may not work.

But he says it’s well worth the effort to study the possibilities, in part because much of the research will also improve our understanding of glacier dynamics and the risks of sea-level rise—and in part because it’s only a question of when, not if, Thwaites will collapse.

Even if the world somehow halted all greenhouse gas emissions tomorrow, the forces melting that fortress of ice will continue to do so.

So one way or another, the world will eventually need to make big, expensive, difficult interventions to protect people and infrastructure. The cost and effort of doing one project in Antarctica, he says, would be small compared to the global effort required to erect thousands of miles of seawalls, ratchet up homes, buildings, and roads, and relocate hundreds of millions of people.

“One thing is challenging—and the other is even more challenging,” Minchew says. “There’s no easy path forward.”