Just a few short days ago, the Department of Energy announced that the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions had fallen by 3.5% last year – due in large part to a new record for renewable energy generation, such as wind and solar, which now powers more than 50% of the UK’s electricity supply.

Greenpeace UK policy director Doug Parr said it showed “the UK’s efforts to tackle climate change are working,” and called on the government to “rapidly make renewables the backbone of our energy system to lower our bills for good.”

The UK’s expansion of renewable energy infrastructure and capacity has certainly proven valuable in recent months, as repeated disruptions have continued to impact the supply of fossil fuels from abroad, and skyrocketing energy prices have underscored the need for greater energy security and independence.

However, as the country celebrates this new milestone on the journey to net zero, there are significant obstacles that still lie ahead – such as the lack of long-term financing and the challenges of renewable energy intermittency.

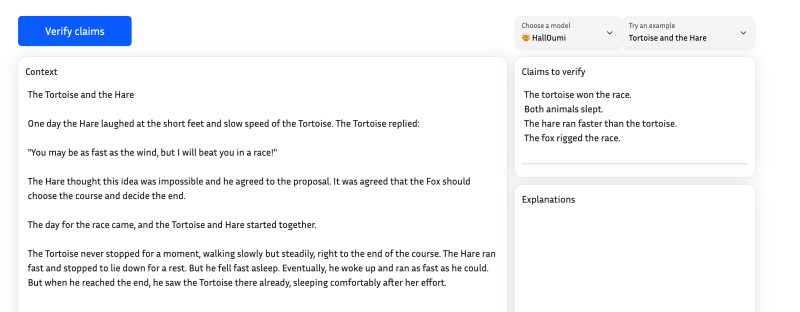

However, the most significant complication threatening to undermine the UK’s energy transition is not related to the performance or cost of renewable energy, but rather to the availability of the materials that are needed to build and scale a clean energy system.

Critical minerals such as lithium, nickel, cobalt, copper and rare earth elements are essential components of rapidly growing energy technologies – including wind turbines, electricity networks and electric vehicles – and securing a stable and reliable supply of these resources has proven to be an incredibly competitive process.

Rare earth boom

As of 2025, the rare earth metals market is projected to reach $8.15 billion, growing at a compound annual growth rate of 7.9%. The energy sector’s demand has been a key driver of this surge, with lithium demand tripling, cobalt demand increasing by 70%, and nickel demand rising by 40% between 2017 and 2022.

Looking ahead, the International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts that by 2040, the world may need four times as many critical minerals for clean energy technologies as it does today. This exponential growth is reflected in projections for the energy transition minerals market, expected to reach $769 billion by 2040.

While consumption is clearly set to grow at a rapid pace, supply is far more limited. As of today, the IEA projects that the world is on track to meet only 70% of global copper demand and 50% of lithium demand by 2035, while the majority of growth in the supply of lithium, nickel, cobalt and rare earth elements will come from just a handful of countries.

For the UK this is a concerning trend, as it has remained far too reliant on exports from unstable sources, and is now faced with the difficult task of improving its critical mineral supply chain amidst a global race for these materials.

In response, the UK government is preparing to launch a new critical minerals strategy this spring which is designed to support the “industries of tomorrow”. This new strategy will differ from the previous version – announced in 2022 – by adopting a more targeted and long-term approach, with a particular focus on collaborating with new international partners in order to secure stable supplies.

Such an approach echoes the EU’s latest efforts to actively forge new partnerships with emerging markets and developing economies under its Global Gateway initiative.

Critical Minerals Strategy

Recent attempts to implement this outward-looking strategy have made international headlines, including the EU’s ambitious effort to strike a critical minerals deal with Ukraine – which is home to vast reserves of rare earth minerals.

Of course, given the UK’s own steadfast and public support of Ukraine, exemplified by the £2.26bn loan extended last week, Prime Minister Keir Starmer could very well try his own luck at forging a similar partnership with the embattled country. The more strategic choice would be to explore the opportunities presented by other nations who face far less complications, and whose mineral potential is far greater than the existing market size.

Once such nation is Pakistan, Asia’s sleeping giant and a fast-growing economic force on the world stage. With 92 identified minerals—including significant reserves of copper, gold, and rare earth elements—Pakistan could supply substantial amounts of raw materials needed for the UK’s green transition, while remaining a stable and reliable partner that is unaffected by the battle for mineral supremacy that embroils China and the United States.

In fact, despite contributing just 3.2% to GDP, Pakistan’s mining sector has attracted giants like Barrick Gold, and projects such as the Reko Diq are poised to produce significant quantities of copper and gold for the foreseeable future.

The upcoming Pakistan Mineral Investment Forum, which is set to unfold in Islamabad next week, will certainly feature key stakeholders in the global mining sector, including government officials and industry leader who are keen to explore the country’s supportive policy frameworks and untapped mineral reserves. The UK must ensure its presence is also felt, as a partnership with Pakistan could offer an invaluable opportunity to diversify its supply chain.

As geopolitical tensions persist and supply chains remain vulnerable, the UK’s energy transition is truly made most vulnerable by its lack of a steady and stable supply of critical minerals. While the government’s upcoming 2025 Critical Minerals Strategy aims to bolster resilience through international collaboration and domestic investment, its success will hinge on aggressively diversifying partnerships to reduce overreliance on concentrated markets.

Without this, the UK’s clean energy future, along with its long-term economic growth, is at risk.