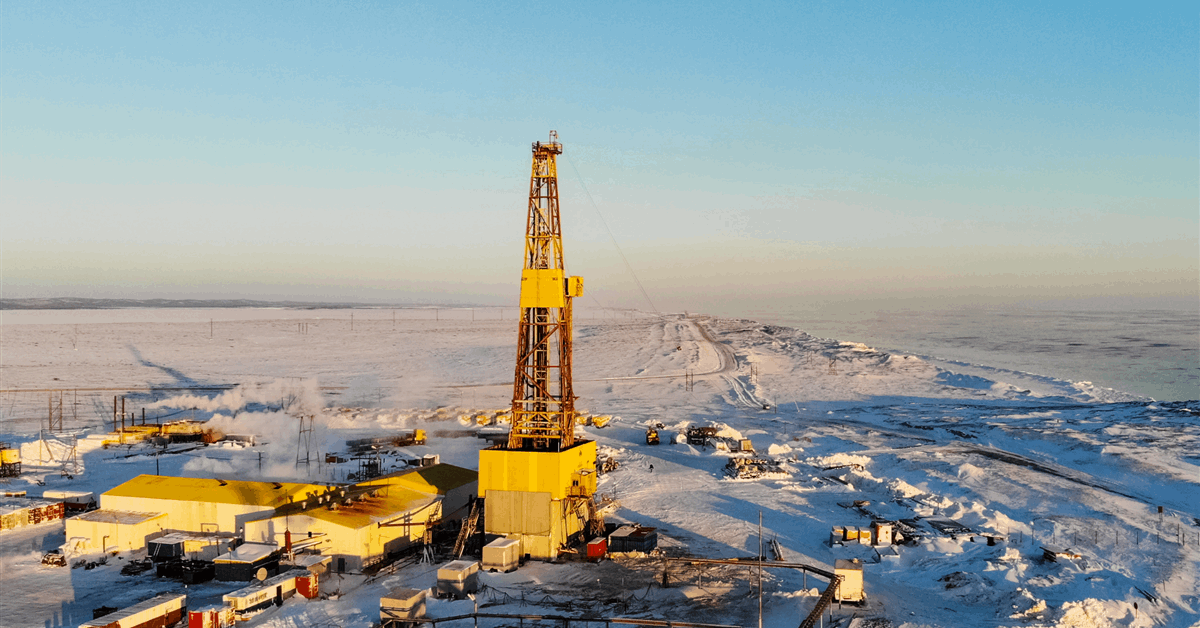

Russia’s oil producers have been drilling wells at a pace not seen in at least five years as the nation readies for both a loosening of OPEC+ output limits and the possibility of relief from some international sanctions over its invasion of Ukraine.

The level of activity, which is also more than a third above the pre-war level, is the latest sign of the Russian oil industry’s resilience to Western sanctions, which were designed to cripple the country’s long-term ability to pump crude by restricting access to advanced technologies and equipment.

The drilling activity means Russia’s total capacity for producing crude and a light oil called condensate is 11 million to 11.5 million barrels a day, virtually unchanged from 2016, said Ronald Smith from Emerging Markets Oil & Gas Consulting Partners LLC.

“We can safely say that the Russian oilfield service industry has, for the most part, successfully adapted to the sanctions regime,” said Smith. “This does not mean that a perfect replacement has been found in all cases, but that suitable substitutes exist at a broader level.”

Russia’s production drilling averaged more than 2,370 km (7.8 million feet) in January and February, according to the latest available data seen by Bloomberg. That’s higher than the seasonal average for the first three years of the Kremlin’s invasion in Ukraine, which triggered broad restrictions on the availability of western oilfield services in Russia, historical data show.

Even as some major foreign providers left the country in the wake of the invasion, they sold Russian units to local managers, keeping the equipment and the expertise in the sanctioned nation, while other suppliers including SLB Plc and Weatherford International Plc have continued to operate, although on a smaller scale.

Over the past three years, local service companies have also been able to find alternative equipment providers or develop their own equivalents, according to Dmitry Kasatkin, a partner at Kasatkin Consulting, which employs some former Deloitte consultants in the region.

“There might be some degree of regress in drilling technologies, like shorter horizontal legs, fewer fracking stages, less precise well bore positioning,” said Sergey Vakulenko, who spent a decade as an executive at a Russian oil producer and is now a scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “In general, the impact of the sanctions and departure of the western service providers is much lower than what was predicted by many three years ago.”

Russia’s Energy Ministry did not comment on the pace of the nation’s oil-drilling and impact of the western sanctions. SLB and Weatherford also did not respond to emailed requests for comments on their current activities and business plans in Russia.

Maturing Fields

Russian oil producers need to maintain a fast pace of drilling to ensure the nation can ramp up crude output in line with the OPEC+ plan to relax output restrictions.

Currently, Russia relies on fields mostly discovered and brought online in the Soviet times for around 95% of its crude and condensate output, according to estimates from Moscow-based Yakov and Partners consultancy.

“The reserves are not depleted, far from it, but lower-hanging fruits have been picked and now the Russian oil industry has to try harder for the same outcome” in terms of production rates, Vakulenko said.

Russia’s strategy seems to focus on more-advanced horizontal drilling at mature fields, especially in western Siberia, analysts said. Right now, horizontal wells account for around 80 percent of production drilling in this mature Russian oil province, according to Kasatkin. By 2030, this share may grow to 95 percent, making drilling at western Siberia similar to that in the US Permian Basin, he said.

The share of horizontal wells in Russia’s total drilling rates increased to about two thirds, compared to 50 percent in 2020, according to data seen by Bloomberg.

Drilling for the Future

There is one area where Russia’s oil-drilling has fallen behind – exploration.

In January-February, the monthly pace of drilling to discover new oil reserves averaged just 46 kilometers, compared to nearly 68 kilometers in the first two months of last year, and nearly 75 kilometers in the pre-war winter months of 2022.

“Amid growing market uncertainty, volatile and low oil prices, the first thing producers give up is green-field exploration,” said Dmitry Kasatkin. Double-digit borrowing costs in Russia as well as labor shortages are also a factor behind the reduced exploration efforts, Vakulenko said.

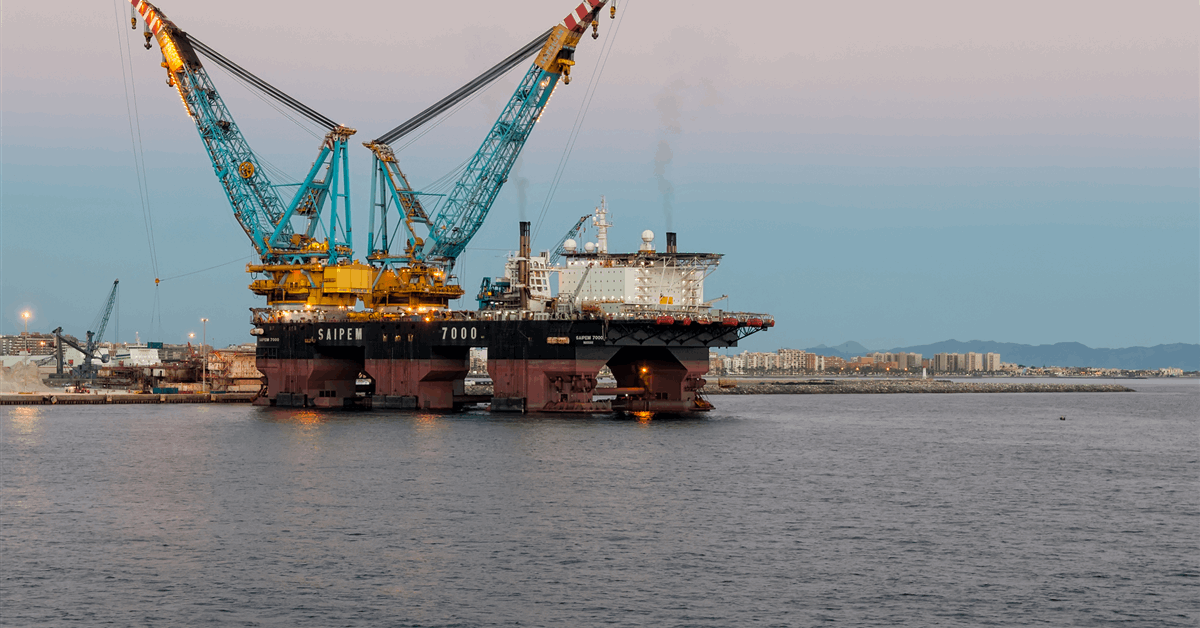

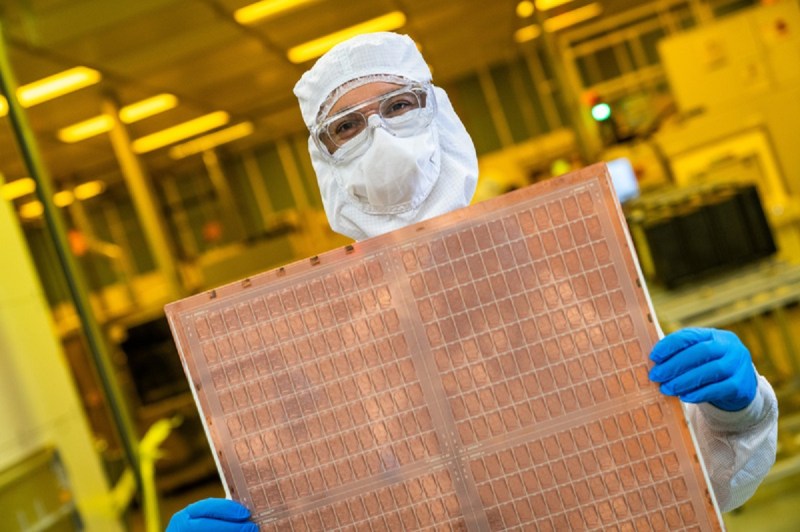

Lower exploration drilling is also a result of a lack of cutting-edge technologies needed to tap particularly complicated reserves offshore or in the Arctic, said Anna Volkova, expert at Yakov and Partners. Both the EU and the US ban supplies of such equipment and technologies to Russia.

Kasatkin expects Russia’s oil-exploration efforts to remain fairly muted until around 2030, when new fields will need to be found to replace western Siberian reserves, which face heavier depletion from around 2035.

But until then, “Russia has an abundance of more conventional, if increasingly challenging, reserves, for which available technology is more than sufficient,” according to Smith.