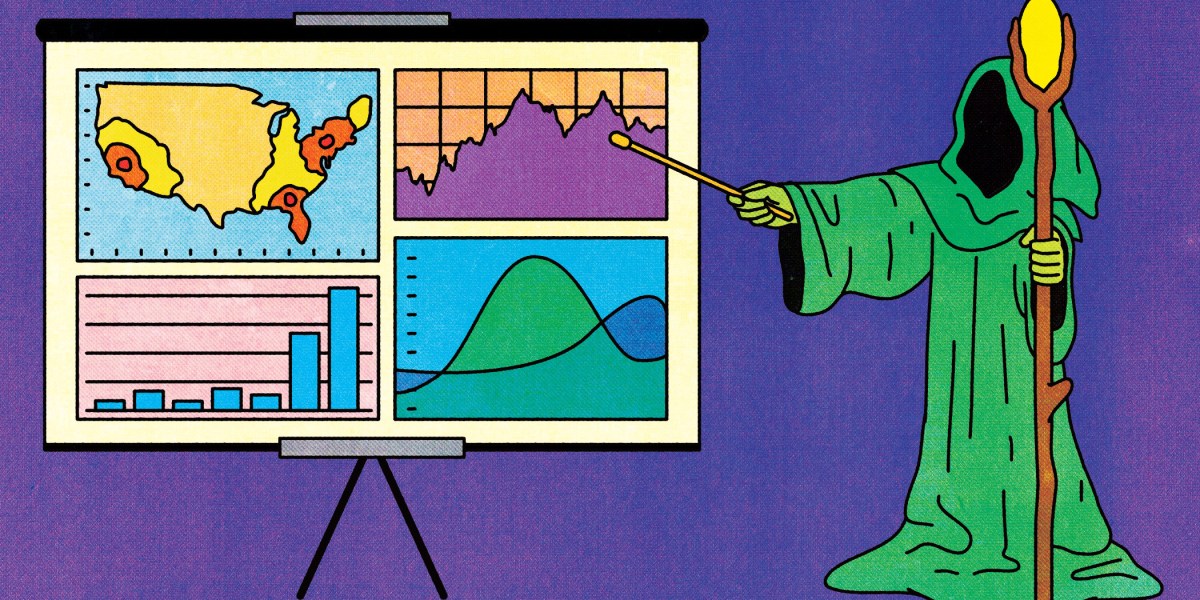

Two new studies from MIT and Harvard Medical School add to a growing body of evidence that infection-fighting molecules called cytokines also influence the brain, leading to behavioral changes during illness.

By mapping the locations in the brain of receptors for different forms of IL-17, the researchers found that the cytokine acts on the somatosensory cortex to promote sociable behavior and on the amygdala to elicit anxiety. These findings suggest that the immune and nervous systems are tightly interconnected, says Gloria Choi, an associate professor of brain and cognitive sciences and one of both studies’ senior authors.

“If you’re sick, there’s so many more things that are happening to your internal states, your mood, and your behavioral states, and that’s not simply you being fatigued physically. It has something to do with the brain,” she says.

In the cortex, the researchers found certain receptors in a population of neurons that, when overactivated, can lead to autism-like symptoms such as reduced sociability in mice. But the researchers determined that the neurons become less excitable when a specific form of IL-17 binds to the receptors, shedding possible light on why autism symptoms in children often abate when they have fevers. Choi hypothesizes that IL-17 may have evolved as a neuromodulator and was “hijacked” by the immune system only later.

Meanwhile, the researchers also found two types of IL-17 receptors in a certain population of neurons in the amygdala, which plays an important role in processing emotions. When these receptors bind to two forms of IL-17, the neurons become more excitable, leading to an increase in anxiety.

Eventually, findings like these may help researchers develop new treatments for conditions such as autism and depression.