Much has been said about the “size of the prize” for the supply chain from ambitious plans to install hundreds of vast wind turbines bobbing in the North Sea.

Offshore Wind Scotland estimates developers will be splashing out £50 billion to build 25GW of offshore wind capacity, making a whirlwind of cash available for port operators, blade manufacturers, vessel operators – as well as the providers of everything that happens below the waterline.

This includes moorings, anchors, cables, connectors and buoyancy systems – not to mention survey, sensing technology and data measuring the movement of the waves and the volume of fish.

Luckily, much of the subsea technology that will build the wind farms has largely been developed for that other North Sea energy industry – oil and gas – which pioneered the skills and technology to produce tens of billions of barrels in one of the world’s harshest environments over the last 50 years.

This same subsea expertise is thought to be essential to delivering floating offshore wind (FOW) over the next five to ten years. Many supply chain firms grown over decades working in the oil and gas industry are now focused on this prize, although many are also questioning if the targets are feasible.

© Supplied by First Marine Solutio

© Supplied by First Marine SolutioBut Steve Brown, managing director of First Marine Solutions, is taking a pragmatic view – even if ambitions are greatly reduced.

“If you look at the size of the prize and split it into three, it’s still huge anyway. Divide it by three or four and it still makes loads of sense,” he says.

Brown and Martin Suttie, chairman of First Tech Group, spoke to Energy Voice ahead of the Subsea Expo. The group comprises three main separate companies including First Subsea, First Marine and First Integrated Solutions, which recently acquired the Teesside rentals business – Tusk Lifting – from Mammoet, part of the Dutch conglomerate that owns retail chain Makro.

Between them, the businesses are roughly the same size in terms of income, a near even three-way split of the £57 million the group made in the year ending April 2024.

Suttie, who five years ago took over the helm of the business founded by his father Ian, said last year was “quite close to the best year ever” for all three businesses and in turn for First Tech, which also reported a consolidated £4.8m pre-tax profit.

First Subsea traditionally provided connectors for floating, production, storage and offloading (FPSO) units, but took an early decision to shift over into renewables (including in cable protection for some fixed wind projects in 2013), and moved into floating wind when it picked up some work on Kincardine – one of the UK’s first and largest floating offshore wind schemes.

It is in this sector that Suttie and Brown expect “exponential growth” for the business – even if the size of the prize is a fraction of the estimate.

“Floating wind is a great opportunity for the oil and gas industry, because who knows better how to moor things in deep water and how cables need to be controlled in deep water, buoyancy, vessels. They are all the same skill sets,” says Suttie.

“The subsea sector in oil and gas is well set up for floating wind. That is the one bit we can hang our hat on in Aberdeen. We have a great subsea sector.

“Now there are loads of challenges about size of ports and the difficulty of the operations – grid connection, the size of the turbines, the weather impact – there are lots of problems.

“But the people that are going to solve this problem are oil and gas people.

“Because the balance sheets of the big companies have the ability to do it.

“The subsea companies have the expertise.

“If it is going to happen, it is going to happen through the oil and gas industry and that is why it is exciting for me as an Aberdonian. We could do this. ‘Will we do it’ is a different question.”

The bit below the water

The critical difference between fixed wind, which is well established while floating wind is still nascent, is “the bit below the water”.

Suttie says the group is investing in the business for FOW, and estimates the group now has seven to eight full-time dedicated employees and is looking at product design as well as deploying the firm’s experience of moorings.

“We spend a lot of time with the operators. We have done a good job of showing our importance,” says Suttie.

“The mooring bit is like putting the Eiffel Tower in the North Sea with a sail.

“That is the critical difference from fixed wind. The turbine sizes are a bit bigger, but it is the bit below the water that is changing. So therefore it becomes a mooring question.

“If we can help solve that for the operator then hopefully we can create a long-lasting and fast-growing business as well.”

The problem – and the opportunity for floating offshore wind – is that there is “no silver bullet” yet identified for a range of challenges in the sector.

© Supplied by Green Volt

© Supplied by Green VoltBrown, who first joined Suttie at the group in 2014, says: “One of the biggest problems is access to the hardware. You’ve got a very limited supply chain of those components and none of them are in the UK bar the buoyancy.

“If you look at chain, anchors, connectors, ropes – these things are all generally manufactured at scale out with the UK.

“As a lot of these projects concertina – a 2029, 29, 30 install – it’s a bit of a challenge.”

Suttie is also sceptical of estimates for job creation, but is adamantly on the side of supporting the oil and gas industry to fund the supply chain.

“We are not going to employ 12,000 people today in floating wind – we are probably never going to employ 12,000 people offshore.

“But there are a lot of jobs potentially to come from floating offshore wind. So how do we get there?

“We have to encourage the oil and gas industry to develop more fields. It is not going to be 15 tomorrow, [but] there are going to be some hopefully.

“There’s going to be a decommissioning phase as well, which helps bridge the gap. And then you get to floating wind.

“Fixed wind isn’t exciting for Aberdeen. It’s not exciting for oil and gas companies because the technology is proven.”

Brown also notes that the market for fixed wind is mainly already stitched up by four or five mostly European companies.

Suttie interjects: “We are too late. Floating wind is exciting and obviously there is carbon capture and hydrogen, but we are not focused on that.

“Floating is a huge opportunity for the Aberdeen oil and gas offshore skill set. We knew that three years ago when Subsea Expo was here and we were absolutely buzzing about it, and nothing has happened in three years, pretty much.”

Brown says the firm has used those fallow years to invest in capabilities. “That’s been good for us as a group. We are one of the few companies prepared to spend money now. We have made good progress in that time; we are in a much better position now than we would have been maybe 18 months ago.”

Wind behind the sails

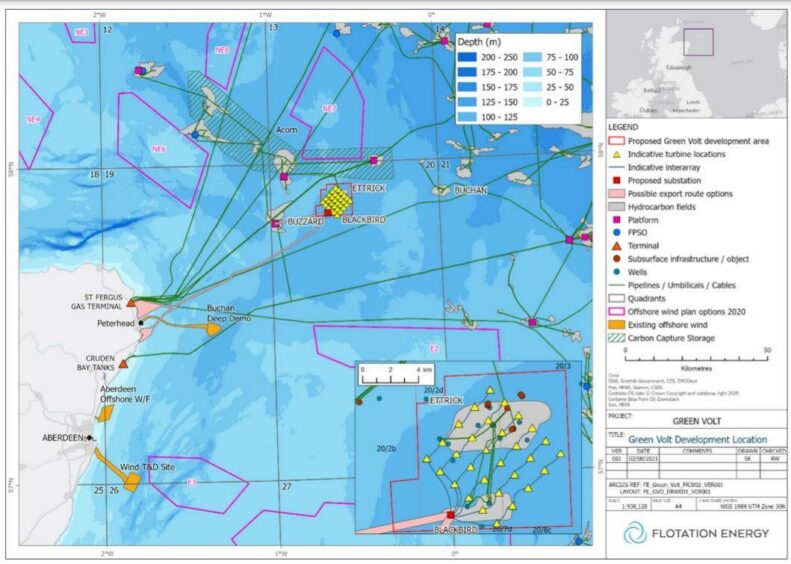

If there is one thing government could do to put impetus behind the sails of floating offshore wind, it is to ensure the Green Volt floating offshore wind project goes ahead. The 560 GW project led by Flotation Energy and Vårgrønn was the first floating project to win funding under the UK government’s most recent contracts for difference funding scheme, known as AR6.

The scale of the project will “unlock” the rest, he believes.

“This is a whole different ball game,” he says. The moorings and connectors for each of the project’s floating turbines is not unlike the sort of subsea engineering required to keep an FPSO grounded to an oil and gas field. Except instead of the one FPSO, GreenVolt will have up to 35.

“If you think about moving an FPSO that is a big thing in oil and gas. Imagine if we had an oil field that needed 30 FPSOs,” says Suttie.

30 floating turbines is a whole different ball game. If we can do that we can export that all around the world.”

“We shouldn’t take it lightly because it is only 30 turbines and we have seen all these fixed wind fields with 300 turbines. This 30 is a whole different ball game. If we can do that we can export that all around the world.”

Another key to ensuring that the supply chain benefits from offshore wind is to make sure the oil and gas industry pays the supply chain enough to invest in the skills and capacity that will be needed.

First Tech is a patient investor willing to take a longer view than the typical three-to-five year window for private equity firms, and longer still for some other trade buyers. Suttie and Brown foresee sticking with the sector for the long haul.

“That is where some businesses may struggle with renewables, if you have got a management team that might be coming too close to retirement. How do you get motivated for something that is happening in 2030?” says Brown.

Meanwhile, Suttie is critical of the UK government’s tax on oil and gas companies, which is undermining investment in the North Sea – either in fresh drilling or decommissioning.

“The frustrating thing is this should be a really exciting time for Aberdeen and it doesn’t feel like that because the policy in oil and gas is a million miles away from what the rhetoric is,” says Suttie.

“If you cut this off and make tens of thousands of people unemployed in Aberdeen in the next two, three or four years, you are going to suffer badly in decommissioning and the energy transition. And we will fall behind in terms of competing in floating wind with the Far East.

“We have an opportunity to be leading this and selling this service all around the world. And the carbon capture and hydrogen. But there is an awesome opportunity here and they are going to mess it up if they shut the first bit down.

“Now does that mean they are going to mess First Tech Group up? No. There is still plenty.”