Joe Curtatone is president of the Alliance for Climate Transition.

While China now leads the U.S. in the number of patents, the United States has long been the global leader in scientific innovation and technological breakthroughs. From launching the internet to decoding the human genome, our universities, national labs and startup ecosystems have powered progress not just at home, but across the globe.

But that leadership is now at serious risk — especially in climate and tough tech sectors — thanks to a combination of short-sighted federal policies, tariffs, attacks on academic institutions and an increasingly hostile posture toward international students and researchers.

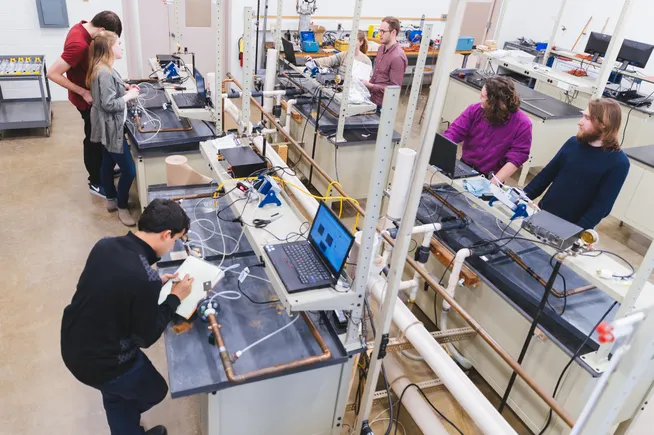

At the heart of this crisis is a growing brain drain — a phenomenon where top talent, including scientists, engineers and entrepreneurs, increasingly look outside the U.S. to study, work and build the technologies of the future.

The warning signs are everywhere. In recent months, we’ve seen sweeping attempts by the current administration to undermine the independence and integrity of university research, especially in areas tied to climate science, advanced energy and environmental policy. Key research grants have been frozen or redirected based on political ideology. Experts have been sidelined or dismissed. Federal agencies have been pressured to strip climate and environmental language from their reports. The message is clear: If your work doesn’t align with the administration’s narrative, you may be punished for it.

Simultaneously, international scholars and students — the lifeblood of many of our top science and engineering programs — are being pushed away. Visas are being revoked without due process, delays are mounting and the overall tone from federal leadership is one of suspicion and exclusion.

This isn’t just bad optics. It directly threatens our innovation economy and the recovery could take decades.

Engineering, environmental science and computer science international students don’t just study here — they launch startups, file patents, drive new discoveries and often stay to build companies that hire American workers. When we shut the door on them, we don’t just lose individuals; we lose the ripple effect of their ideas and impact.

At the same time, American students and researchers, including 75% of those polled in Nature Magazine, are beginning to look elsewhere for higher education, lab space and research dollars, especially those interested in climate and technology fields. Canada, the United Kingdom, the European Union, and even countries like Singapore and Australia are investing in university programs, visa pathways and research incentives designed to attract the very talent the U.S. is pushing away.

This trend is amplified by the fact that other nations are doubling down on venture capital and public investment in clean tech and tough tech sectors. While Washington debates the existence of climate change, countries like Germany, South Korea and the Netherlands are aggressively funding battery innovation, green hydrogen and next-gen energy storage. China has already outpaced the U.S. in solar manufacturing and is gaining ground in electric vehicles and grid-scale technologies. These nations see climate tech not just as a moral imperative but as a defining economic opportunity — one that will shape jobs, industries and global influence for decades.

Meanwhile, the U.S. risks losing its seat at the table.

Let’s be clear: The climate crisis isn’t going away. The demand for clean energy, carbon removal, climate adaptation and climate tech innovation will only grow, regardless of who sits in the White House. The question is whether the U.S. wants to lead this future or fall behind.

We need to reverse course. That means restoring integrity and independence to our research institutions, welcoming international talent instead of repelling it and investing boldly in the technologies that will define the next economy. It also means defending higher education — not undermining it — for its critical role in preparing the next generation of problem-solvers.

Because if we don’t, others will. And we may find that when we’re ready to catch up, the world has already moved on — without us.