A year or so ago, Xiao Li was seeing floods of Nvidia chip deals on WeChat. A real estate contractor turned data center project manager, he had pivoted to AI infrastructure in 2023, drawn by the promise of China’s AI craze.

At that time, traders in his circle bragged about securing shipments of high-performing Nvidia GPUs that were subject to US export restrictions. Many were smuggled through overseas channels to Shenzhen. At the height of the demand, a single Nvidia H100 chip, a kind that is essential to training AI models, could sell for up to 200,000 yuan ($28,000) on the black market.

Now, his WeChat feed and industry group chats tell a different story. Traders are more discreet in their dealings, and prices have come back down to earth. Meanwhile, two data center projects Li is familiar with are struggling to secure further funding from investors who anticipate poor returns, forcing project leads to sell off surplus GPUs. “It seems like everyone is selling, but few are buying,” he says.

Just months ago, a boom in data center construction was at its height, fueled by both government and private investors. However, many newly built facilities are now sitting empty. According to people on the ground who spoke to MIT Technology Review—including contractors, an executive at a GPU server company, and project managers—most of the companies running these data centers are struggling to stay afloat. The local Chinese outlets Jiazi Guangnian and 36Kr report that up to 80% of China’s newly built computing resources remain unused.

Renting out GPUs to companies that need them for training AI models—the main business model for the new wave of data centers—was once seen as a sure bet. But with the rise of DeepSeek and a sudden change in the economics around AI, the industry is faltering.

“The growing pain China’s AI industry is going through is largely a result of inexperienced players—corporations and local governments—jumping on the hype train, building facilities that aren’t optimal for today’s need,” says Jimmy Goodrich, senior advisor for technology at the RAND Corporation.

The upshot is that projects are failing, energy is being wasted, and data centers have become “distressed assets” whose investors are keen to unload them at below-market rates. The situation may eventually prompt government intervention, he says: “The Chinese government is likely to step in, take over, and hand them off to more capable operators.”

A chaotic building boom

When ChatGPT exploded onto the scene in late 2022, the response in China was swift. The central government designated AI infrastructure as a national priority, urging local governments to accelerate the development of so-called smart computing centers—a term coined to describe AI-focused data centers.

In 2023 and 2024, over 500 new data center projects were announced everywhere from Inner Mongolia to Guangdong, according to KZ Consulting, a market research firm. According to the China Communications Industry Association Data Center Committee, a state-affiliated industry association, at least 150 of the newly built data centers were finished and running by the end of 2024. State-owned enterprises, publicly traded firms, and state-affiliated funds lined up to invest in them, hoping to position themselves as AI front-runners. Local governments heavily promoted them in the hope they’d stimulate the economy and establish their region as a key AI hub.

However, as these costly construction projects continue, the Chinese frenzy over large language models is losing momentum. In 2024 alone, over 144 companies registered with the Cyberspace Administration of China—the country’s central internet regulator—to develop their own LLMs. Yet according to the Economic Observer, a Chinese publication, only about 10% of those companies were still actively investing in large-scale model training by the end of the year.

China’s political system is highly centralized, with local government officials typically moving up the ranks through regional appointments. As a result, many local leaders prioritize short-term economic projects that demonstrate quick results—often to gain favor with higher-ups—rather than long-term development. Large, high-profile infrastructure projects have long been a tool for local officials to boost their political careers.

The post-pandemic economic downturn only intensified this dynamic. With China’s real estate sector—once the backbone of local economies—slumping for the first time in decades, officials scrambled to find alternative growth drivers. In the meantime, the country’s once high-flying internet industry was also entering a period of stagnation. In this vacuum, AI infrastructure became the new stimulus of choice.

“AI felt like a shot of adrenaline,” says Li. “A lot of money that used to flow into real estate is now going into AI data centers.”

By 2023, major corporations—many of them with little prior experience in AI—began partnering with local governments to capitalize on the trend. Some saw AI infrastructure as a way to justify business expansion or boost stock prices, says Fang Cunbao, a data center project manager based in Beijing. Among them were companies like Lotus, an MSG manufacturer, and Jinlun Technology, a textile firm—hardly the names one would associate with cutting-edge AI technology.

This gold-rush approach meant that the push to build AI data centers was largely driven from the top down, often with little regard for actual demand or technical feasibility, say Fang, Li, and multiple on-the-ground sources, who asked to speak anonymously for fear of political repercussions. Many projects were led by executives and investors with limited expertise in AI infrastructure, they say. In the rush to keep up, many were constructed hastily and fell short of industry standards.

“Putting all these large clusters of chips together is a very difficult exercise, and there are very few companies or individuals who know how to do it at scale,” says Goodrich. “This is all really state-of-the-art computer engineering. I’d be surprised if most of these smaller players know how to do it. A lot of the freshly built data centers are quickly strung together and don’t offer the stability that a company like DeepSeek would want.”

To make matters worse, project leaders often relied on middlemen and brokers—some of whom exaggerated demand forecasts or manipulated procurement processes to pocket government subsidies, sources say.

By the end of 2024, the excitement that once surrounded China’s data center boom was curdling into disappointment. The reason is simple: GPU rental is no longer a particularly lucrative business.

The DeepSeek reckoning

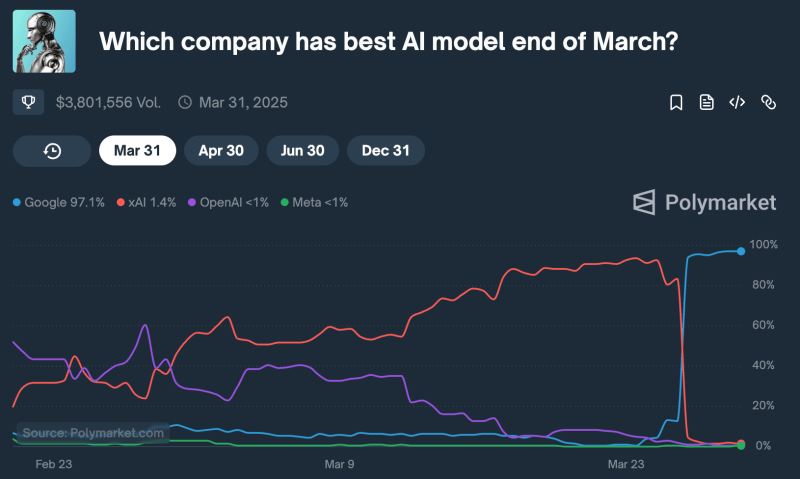

The business model of data centers is in theory straightforward: They make money by renting out GPU clusters to companies that need computing capacity for AI training. In reality, however, securing clients is proving difficult. Only a few top tech companies in China are now drawing heavily on computing power to train their AI models. Many smaller players have been giving up on pretraining their models or otherwise shifting their strategy since the rise of DeepSeek, which broke the internet with R1, its open-source reasoning model that matches the performance of ChatGPT o1 but was built at a fraction of its cost.

“DeepSeek is a moment of reckoning for the Chinese AI industry. The burning question shifted from ‘Who can make the best large language model?’ to ‘Who can use them better?’” says Hangcheng Cao, an assistant professor of information systems at Emory University.

The rise of reasoning models like DeepSeek’s R1 and OpenAI’s ChatGPT o1 and o3 has also changed what businesses want from a data center. With this technology, most of the computing needs come from conducting step-by-step logical deductions in response to users’ queries, not from the process of training and creating the model in the first place. This reasoning process often yields better results but takes significantly more time. As a result, hardware with low latency (the time it takes for data to pass from one point on a network to another) is paramount. Data centers need to be located near major tech hubs to minimize transmission delays and ensure access to highly skilled operations and maintenance staff.

This change means many data centers built in central, western, and rural China—where electricity and land are cheaper—are losing their allure to AI companies. In Zhengzhou, a city in Li’s home province of Henan, a newly built data center is even distributing free computing vouchers to local tech firms but still struggles to attract clients.

Additionally, a lot of the new data centers that have sprung up in recent years were optimized for pretraining workloads—large, sustained computations run on massive data sets—rather than for inference, the process of running trained reasoning models to respond to user inputs in real time. Inference-friendly hardware differs from what’s traditionally used for large-scale AI training.

GPUs like Nvidia H100 and A100 are designed for massive data processing, prioritizing speed and memory capacity. But as AI moves toward real-time reasoning, the industry seeks chips that are more efficient, responsive, and cost-effective. Even a minor miscalculation in infrastructure needs can render a data center suboptimal for the tasks clients require.

In these circumstances, the GPU rental price has dropped to an all-time low. A recent report from the Chinese media outlet Zhineng Yongxian said that an Nvidia H100 server configured with eight GPUs now rents for 75,000 yuan per month, down from highs of around 180,000. Some data centers would rather leave their facilities sitting empty than run the risk of losing even more money because they are so costly to run, says Fan: “The revenue from having a tiny part of the data center running simply wouldn’t cover the electricity and maintenance cost.”

“It’s paradoxical—China faces the highest acquisition costs for Nvidia chips, yet GPU leasing prices are extraordinarily low,” Li says. There’s an oversupply of computational power, especially in central and west China, but at the same time, there’s a shortage of cutting-edge chips.

However, not all brokers were looking to make money from data centers in the first place. Instead, many were interested in gaming government benefits all along. Some operators exploit the sector for subsidized green electricity, obtaining permits to generate and sell power, according to Fang and some Chinese media reports. Instead of using the energy for AI workloads, they resell it back to the grid at a premium. In other cases, companies acquire land for data center development to qualify for state-backed loans and credits, leaving facilities unused while still benefiting from state funding, according to the local media outlet Jiazi Guangnian.

“Towards the end of 2024, no clear-headed contractor and broker in the market would still go into the business expecting direct profitability,” says Fang. “Everyone I met is leveraging the data center deal for something else the government could offer.”

A necessary evil

Despite the underutilization of data centers, China’s central government is still throwing its weight behind a push for AI infrastructure. In early 2025, it convened an AI industry symposium, emphasizing the importance of self-reliance in this technology.

Major Chinese tech companies are taking note, making investments aligning with this national priority. Alibaba Group announced plans to invest over $50 billion in cloud computing and AI hardware infrastructure over the next three years, while ByteDance plans to invest around $20 billion in GPUs and data centers.

In the meantime, companies in the US are doing likewise. Major tech firms including OpenAI, Softbank, and Oracle have teamed up to commit to the Stargate initiative, which plans to invest up to $500 billion over the next four years to build advanced data centers and computing infrastructure. Given the AI competition between the two countries, experts say that China is unlikely to scale back its efforts. “If generative AI is going to be the killer technology, infrastructure is going to be the determinant of success,” says Goodrich, the tech policy advisor to RAND.

“The Chinese central government will likely see [underused data centers] as a necessary evil to develop an important capability, a growing pain of sorts. You have the failed projects and distressed assets, and the state will consolidate and clean it up. They see the end, not the means,” Goodrich says.

Demand remains strong for Nvidia chips, and especially the H20 chip, which was custom-designed for the Chinese market. One industry source, who requested not to be identified under his company policy, confirmed that the H20, a lighter, faster model optimized for AI inference, is currently the most popular Nvidia chip, followed by the H100, which continues to flow steadily into China even though sales are officially restricted by US sanctions. Some of the new demand is driven by companies deploying their own versions of DeepSeek’s open-source models.

For now, many data centers in China sit in limbo—built for a future that has yet to arrive. Whether they will find a second life remains uncertain. For Fang Cunbao, DeepSeek’s success has become a moment of reckoning, casting doubt on the assumption that an endless expansion of AI infrastructure guarantees progress. That’s just a myth, he now realizes. At the start of this year, Fang decided to quit the data center industry altogether. “The market is too chaotic. The early adopters profited, but now it’s just people chasing policy loopholes,” he says. He’s decided to go into AI education next.

“What stands between now and a future where AI is actually everywhere,” he says, “is not infrastructure anymore, but solid plans to deploy the technology.”