Rising energy demand, inflation, grid investment, extreme weather and volatile fuel costs are increasing the cost of electricity faster than many households can keep up, and there are no easy fixes, experts say.

Mitigating the problem would require threading a needle of policy alternatives, but even with the right policies, it will take time to reduce customer energy burdens. The U.S. Energy Information Administration puts the national average residential price per kilowatt hour in 2026 at 18 cents, up approximately 37% from 2020.

“I don’t see hidden costs that can be suddenly squeezed out of the system,” said Ray Gifford, managing partner of Wilkinson Barker Knauer’s Denver office and former chair of the Colorado Public Utilities Commission. “You are talking about an industry where most of the costs are fixed, and the assets are long-lived.”

Energy affordability has recently become politically salient, but for many low-income people, “the energy affordability crisis is not new,” said Joe Daniel, a principal on the Rocky Mountain Institute’s carbon free electricity team.

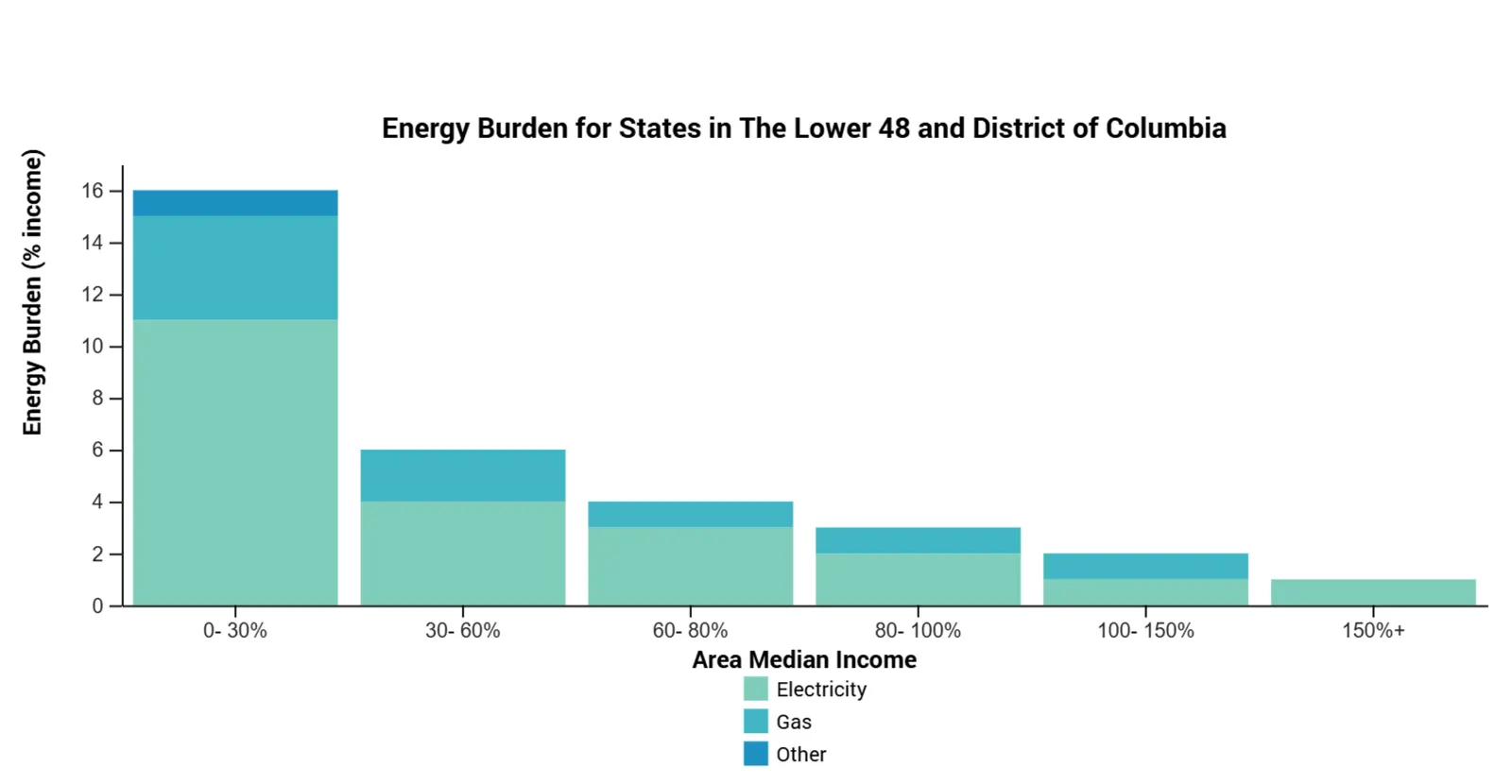

In 2017, 25% of all U.S. households — more than 30 million — faced a high energy burden, defined as paying more than 6% of income on energy bills, according to a report from the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. For the poorest, it can be much higher. Households making less than 30% of area median income paid about 11% of their income for electricity alone, according to data from the Department of Energy covering the years 2018 to 2022.

The Department of Energy’s Low-Income Energy Affordability Data Tool shows households’ energy burden in the lower 48 states and Washington, D.C. The data is based on the American Community Survey 5-year Estimates for 2018-2022.

“What is new is that because electricity prices have outpaced inflation, and, more importantly, dramatically outpaced wages, moderate- and middle-income families are starting to feel the squeeze,” Daniel said.

Between December 2023 and June 2025, household energy arrearages rose by about 31%, according to the National Energy Assistance Directors Association. Forced disconnections for nonpayment are also rising, from 3 million in 2023 to 3.5 million in 2024 and potentially 4 million in 2025, it said.

The increases in electricity prices have not been felt evenly across the country, and the reasons for their rise also vary by region. Still, residential rates have risen faster than those for commercial and industrial customers, and the prices charged by investor-owned utilities are higher and have risen faster than those charged by public power utilities, raising pressure on regulators and elected officials to try to rein in costs.

At least six states introduced legislation last year to limit utilities’ return on equity. California’s Public Utilities Commission recently lowered utilities’ ROE in that state by 0.3 percentage points. And newly elected New Jersey Governor Mikie Sherrill used her first day in office to issue executive orders seeking to freeze electricity cost increases and direct regulators to “modernize” the electric utility business model by making profits “less dependent on capital spending.”

Investors are spooked. Jefferies reported “considerable inbound concern from investors of all types” in January, ahead of Sherrill’s inauguration, related to the anticipated freeze.

But some consumer advocates question whether actions taken now will be too little, too late.

“They’re freezing rates at the highest they’ve ever been,” said Mark Wolfe, executive director of the National Energy Assistance Directors Association.

Low-income customers are “continually falling behind,” and utilities “spend considerable resources trying to collect,” he said. “I don’t think it works, especially as electricity gets more and more expensive, going up faster than incomes.”

Jay Griffin, a former utility regulator and executive chair for the Regulatory Assistance Project, recently wrote that utility business model reform “isn’t just an abstract policy debate, it’s a practical necessity.”

“By rewarding capital investment over outcomes, the model encourages utilities to ‘spend money to make money,’ while discouraging non-capital solutions like demand management and distributed energy resources,” he said. “This model creates risk for customers and investors alike.”

The electric utility sector says it is working to address affordability issues.

Last year, investor-owned utilities allocated about $7 billion to support customer programs, according to their trade group, the Edison Electric Institute. Those efforts included energy audits and weatherization education, usage-reduction programs for low-income households, bill assistance and payment plans, relief programs and referrals for community support.

President Donald Trump takes the stage to speak during a rally at the Horizon Events Center on Jan. 27, 2026, in Clive, Iowa. As a candidate, Trump promised to slash energy prices, including for electricity.

Win McNamee via Getty Images

“As demand grows in our evolving economy, we will continue building on our long track record of delivering customer savings and supporting families facing financial hardships,” EEI said in an emailed statement.

Rising demand — does it hurt or help?

The reasons for electricity price inflation are myriad and the mechanisms for determining price depend on the market, making it hard to generalize across the entire U.S. Grid investments, rising material and labor costs and natural disasters all play a role, but perhaps the issue that has attracted the most attention is that of large-load data centers and their unprecedented demands for power.

After decades of stagnant growth, the EIA expects demand from the commercial and industrial sectors to grow U.S. electricity consumption by 1% in 2026 and 3% in 2027, “marking the first four years of consecutive growth since 2005–07, and the strongest four-year period of growth since the turn of the century.”

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott and Alphabet and Google CEO Sundar Pichai lead a panel at the Google Midlothian Data Center on Nov. 14, 2025, in Midlothian, Texas. Data centers are driving demand growth after years of stagnation.

Ron Jenkins via Getty Images

Looking further out, the Bank of America Institute projects demand to rise at a 2.5% compound annual rate through 2035. It attributes the growth to not just data centers, but also building electrification, industrial growth and electric vehicles.

Aggressive load forecasts have helped drive capacity prices to new highs in the PJM Interconnection, the largest grid operator in the country. Data center load accounted for $6.5 billion, or 40%, of the $16.4 billion in costs from the PJM Interconnection’s December capacity auction, according to the grid operator’s independent market monitor.

“Generally speaking, the higher the demand, the higher the prices go,” said Marc Brown, the Consumer Energy Alliance’s executive director of Northeast.

“It remains unclear whether broader, sustained load growth will increase long-run average costs and prices.”

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory report

But some research has found that growing demand — from large loads as well as consumer electrification efforts — can also be a grid asset. A study released over the summer from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory concluded that load growth helped depress electricity prices over the past five years, and states with the largest price increases typically featured shrinking customer loads.

“It remains unclear whether broader, sustained load growth will increase long-run average costs and prices,” the researchers said. “In some cases, spikes in load growth can result in significant, near-term retail price increases.”

RMI’s Daniel said higher throughput on the grid can help to lower rates by spreading costs over a broader customer base, and flexible demand can be used to address grid stress and peak loads.

“Done poorly or done correctly, it has the capability of dramatically impacting rates and bills,” he said.

Gifford also said that load growth has the potential to benefit the grid, but only under the right circumstances.

“Load growth, if allocated and planned for properly, can lower per-unit costs to customers on the [transmission and distribution] and even generation side,” Gifford said. But the impacts would take some time to materialize.

A lack of competition in transmission and distribution

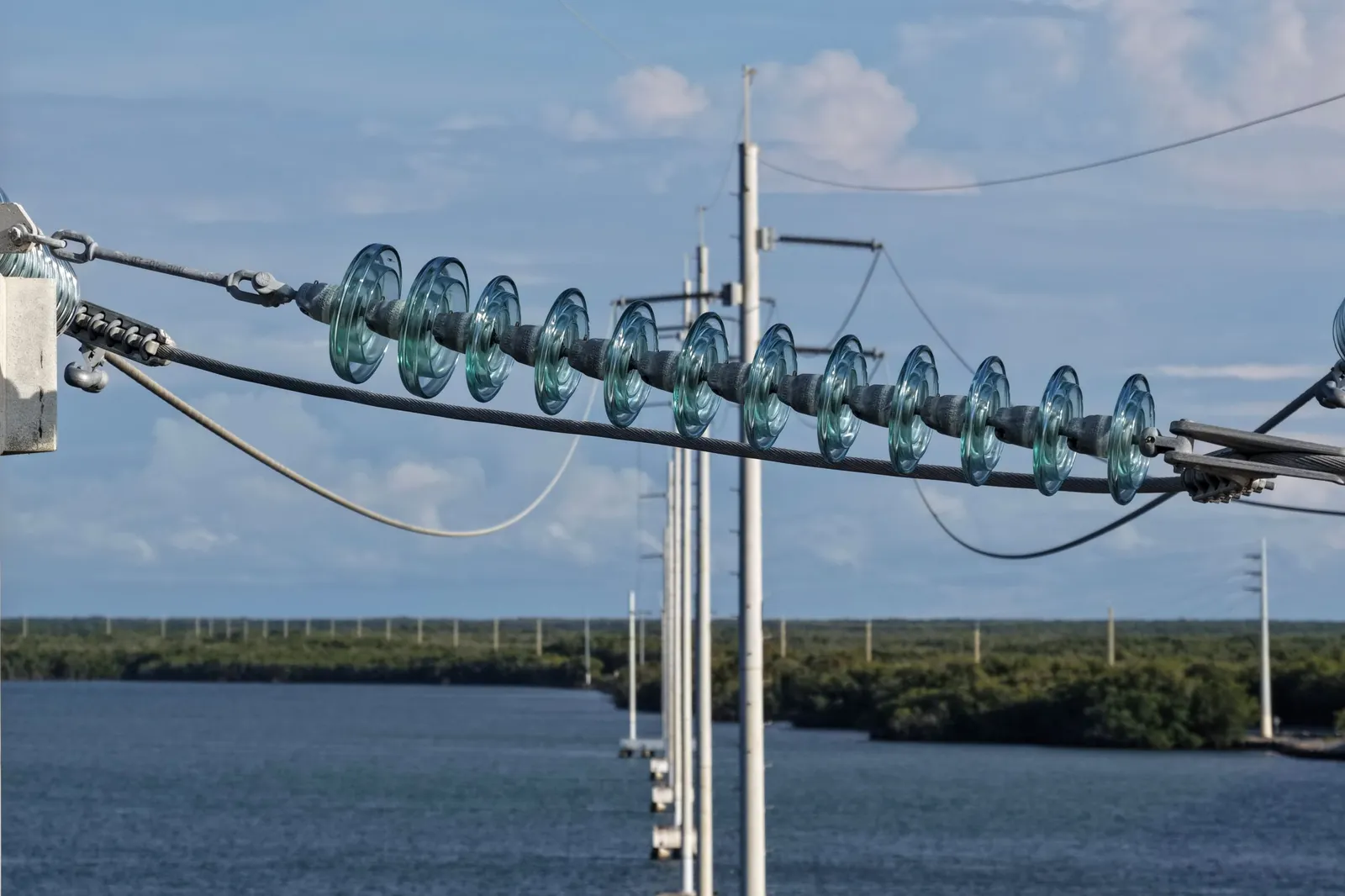

Experts say transmission and distribution costrs are another major driver of rising consumer bills.

“Some of that is because it’s an old grid that needs to get replaced,” said said RMI’s Daniel. “And because of inflation and supply chain issues, the costs to replace an aging grid have gone up.”

Producer price index figures from November show copper wire and cable, as well as switchgear, costs were all up more than 11% year over year and about 60% from 2020. Tariffs, inflation and supply-chain issues have also impacted key components like aluminum, transformers and turbines.

But many of the increases appearing on customer bills now are for infrastructure that was built over the past several years. And some argue the DOE model is incentivizing utilities and infrastructure owners and developers to build more expensively than necessary.

High-voltage power lines run along the electrical power grid on Jan. 14, 2026, in Miami, Fla. Transmission and distribution costs have risen in recent years.

Joe Raedle via Getty Images

There is a “regulatory gap in how transmission gets approved and then put on bills of utilities in parts of the country,” Daniel said. “We are building, essentially, the wrong type of transmission.”

Utilities are building local, supplemental projects “that undergo less scrutiny and still deliver a high rate of return, instead of the larger transmission projects that deliver on affordability and reliability,” he said. A 2024 RMI report, for instance, found that in New England, annual spending on local transmission projects increased eightfold from 2016, to nearly $800 million in 2023. The Berkeley Lab study found that overall, investor-owned utilities’ inflation-adjusted spending on distribution and transmission increased from 2019 to 2024 while generation costs declined.

Paul Cicio, chair of the Electricity Transmission Competition Coalition and president of the Industrial Energy Consumers of America, said the fault lies with regulators.

In 2011, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission issued Order 1000, which requires large transmission projects be subject to competitive bidding. But it made an exception for projects necessary for short-term reliability.

“These are massive amounts of layered in dollars and consumers are on the hook … The cake is baked.”

Paul Cicio

Chair of the Electricity Transmission Competition Coalition and President of the Industrial Energy Consumers of America

The result, Cicio said, was that just 5% of transmission projects are now being competitively bid. The “loophole” was supposed to be closed in 2024 with FERC Order 1920, but the order did not include ratepayer cost containment provisions, he added.

“FERC needs to close that loophole and require that these projects are competitively bid between utilities,” Cicio said. “Affordability is becoming a national political issue. … Electricity costs are now on everybody’s radar.”

Utilities have spent almost $154 billion annually on transmission investments in the last five years, said Cicio, “but that’s only the initial cost.”

When FERC incentives and financing charges are factored in, the cost to consumers winds up being almost $1.8 trillion on transmission in the last five years, he noted.

“These are massive amounts of layered-in dollars, and consumers are on the hook,” Cicio said. “The cake is baked.”

Storms and wildfires require grid upgrades

Industry sources and grid planners say that in addition to building out transmission and distribution, utilities also have to harden the grid in the face of more destructive storms and wildfires.

Last year, U.S. residents lost more power than any year in the previous decade, according to the EIA, with hurricanes a leading cause. The annual average of 11 hours of electricity interruptions was nearly double the annual average of the last 10 years, it said.

On top of the costs of physical grid hardening, the cost of insurance also contributes to higher bills.

In California, which has some of the highest electricity prices in the country, wildfire mitigation efforts cost ratepayers $27 billion between 2019 and 2023, with 40% of that coming from insurance costs, according to the World Resources Institute.

A damaged utility pole is seen as people walk across a makeshift bridge in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene flooding on Oct. 8, 2024, in Bat Cave, N.C. Storms and wildfires require costly grid repaids and upgrades.

Mario Tama via Getty Images

The cost of decarbonization

State policies driving decarbonization can also lead to higher prices, some say.

The Berkeley Lab report linked price increases in recent years to net metered behind-the-meter solar and renewable portfolio standard programs.

States with RPS programs that called for new supplies in the last five years increased retail electricity prices by about 0.4 cents/kWh, the study said. It also found, however, that electricity prices were unaffected by “market-based” utility-scale renewable energy projects built outside of RPS mandates.

Those and other findings are driving some states to rethink their policies. Pennsylvania Republicans forced the state to withdraw from the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative last year, for instance, over affordability concerns.

“Programs like RGGI have seen pretty significant [cost] increases,” said Brown from the Consumer Energy Alliance. Program revenues could be returned to consumers, or expenses capped, he said.

Gifford said states with carbon reduction deadlines may need to rapidly to squeeze out a final 20% of carbon-emitting resources. “You could imagine some of those states reconsidering those mandates or creating a political face-saving way to back off,” he said. “But some of those transition costs are baked in already.”

LNG exports contribute to volatile gas prices

Natural gas prices are one of the biggest determinants of power prices because gas generators tend to set the marginal price of electricity in organized markets, and vertically integrated utilities directly pass fuel costs on to consumers.

The EIA expects the spot price of natural gas at Henry Hub to go down this year by 2% from 2025 before rising against in 2027.

“Natural gas prices increase in our forecast because growth in demand — led by expanding liquefied natural gas exports and more natural gas consumption in the electric power sector — will outpace production growth,” it said.

A cargo ship passes by the Cheniere Energy liquefied natural gas plant on Feb. 10, 2025, in Port Arthur, Texas. Rising LNG exports are helping drive up gas prices domestically, according to experts and government agencies.

Brandon Bell via Getty Images

The advocacy group Public Citizen published a report in December arguing the Trump administration’s policies to increase liquefied natural gas exports are driving higher fuel costs and volatility, and, ultimately, higher electricity bills. Under President Trump, DOE has worked to aggressively increase exports, which the agency says are approximately 25% above 2024 levels.

An average U.S. household paid over $124 more on its utility bills in the first nine months of 2025 than in the same period a year earlier due to rising natural gas prices, according to the report.

“And the driver of this, that everyone in the industry acknowledges, is overwhelmingly record LNG exports that are just getting bigger and bigger,” said Tyson Slocum, director of Public Citizen’s energy program.

Eight U.S. LNG export facilities now use more natural gas than all 74 million domestic gas utility household consumers, he said, adding: “That’s madness.”

“If you start to take steps to reduce demand by LNG exporters, it is going to have a downward effect on domestic gas prices,” Slocum said.

Customer support solutions

While experts and government agencies that track electricity prices see little hope for relief this year, some utilities and states are emphasizing bill assistance and other programs intended to help lower-income households in particular.

But NEADA’s Wolfe said the programs don’t go far enough, and changes are necessary, particularly for low-income customers.

“There should be no charge,” he said, for a “base amount of electricity for very-low-income families.”

NEADA has also been critical of the Trump administration’s attitude toward the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, known as LIHEAP, a federally-funded, state-administered utility bill assistance program that has helped families afford power for decades.

In April, the Department of Health and Human Services fired the entire LIHEAP program staff, and the administration proposed eliminating funding for the program in fiscal year 2026. The future of the program remains uncertain as lawmakers negotiate government funding.

Even if LIHEAP survives, its budget would need to be increased “maybe 5-10 times in order to actually fully address the problem,” said Daniel.

Utilities and governments should lean into low-income programs that directly provide energy assistance and support, he said.

Fewer unpaid bills means fewer utility write-offs, which ultimately are paid by all customers. Those programs “tend to be far more cost-effective than we used to think,” he said, and “actually could drive down rates and bills for everybody.”