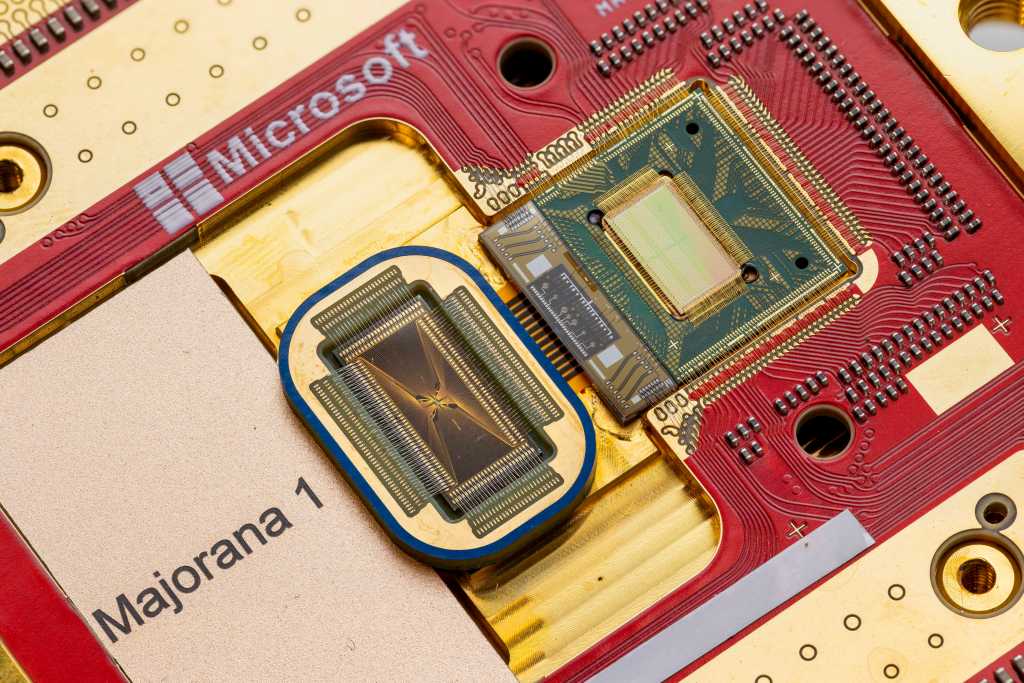

The global race to develop sophisticated, versatile AI models is driving a surge in development of the physical infrastructure to support them. Microsoft, Amazon, Meta and Google parent Alphabet — four of the AI industry’s biggest players — plan to invest a combined $325 billion in capital expenditures in 2025, much of it for data centers and associated hardware.

The technology giants’ spending plans mark a 46% increase from their combined 2024 capital investments, according to Yahoo! Finance, and track a doubling in proposed data centers’ average size from 150 gigawatts to 300 gigawatts between January 2023 and October 2024. In December, Meta said it would build a $10 billion, 4 million-square-foot data center in Louisiana that could consume the power output equivalent of two large nuclear reactors.

The planned spending announcements came after the January release of the highly efficient, open-source AI platform DeepSeek, which led some experts and investors to question just how much infrastructure — from high-performance chips to new power plants and electrical equipment — the AI boom actually requires. But experts interviewed by Facilities Dive see AI efficiency gains as a net positive for data center developers, operators and customers in the long run, despite shorter-term uncertainty that could temporarily create overcapacity in some markets.

“Every technology has gotten more efficient”

DeepSeek’s late January commercial launch took many Americans by surprise, but the rise of a more efficient and capable AI model follows a well-worn pattern of technology development, said K.R. Sridhar, founder, chairman and CEO of power solutions provider Bloom Energy.

“In 2010, it took about 1,500 watt-hours to facilitate the flow of one gigabyte of information,” Sridhar said. “Last year it took about one tenth of that … [but] the total growth of traffic, and therefore the chips and energy, has been twice that amount.”

As generative AI model development has grown more capital intensive, the benefits of efficiency have increased as well, Morningstar DBRS Senior Vice President Victor Leung wrote in a Jan. 28 research note.

“DeepSeek’s approach to constructing and training its model could be viewed as manifesting this drive towards more efficient models and to be expected as they and other companies seek to reduce AI deployment costs,” Leung said. Continued efficiency improvements could moderate demand for data center capacity over the longer term, Leung added.

As evidenced by the tech giants’ recent announcements, the biggest AI players are unlikely to pull back on planned investments on DeepSeek’s account, Ashish Nadkarni, group vice president and general manager for worldwide infrastructure research at IDC, told Facilities Dive.

For companies like Meta and Microsoft, the drive to build as much AI capacity as quickly as possible is “existential,” with Apple the only major tech company to buck the trend so far, Nadkarni said. Those companies, and others like Elon Musk’s xAI, are using huge amounts of proprietary data to train differentiated foundational models useful in building emerging “agentic AI” tools and other future innovations, he added.

Less training, more inference and a cooling rethink?

Despite the scale of their planned and in-progress AI investments, the big tech companies “remain at the starting line,” with commercial payoff uncertain and likely still years away, Nadkarni said.

Imminent advances that allow more cost-effective AI deployments could “stabilize the AI industry in the long run” by reducing the risk of a capital spending pullback that could lead to “a burst investment bubble in AI-related sectors,” Leung wrote.

A reduction in the computing power needed to train new models could eventually tip the balance of new data center deployments toward smaller “inference” data centers, which serve user requests rather than model development and refinement, experts say. That would mean proportionally fewer developments on the scale of Meta’s two-gigawatt Louisiana facility or Compass Datacenters’ planned campus in suburban Chicago that could eventually host five massive data centers.

“An acceleration of [large language models] in large training data centers will lead to a natural acceleration of inference data centers … located in proximity to people, processes and machines,” Sridhar said. Inference data centers typically consume tens of megawatts of power, compared with hundreds of megawatts for centralized training facilities.

For now, data center proposals continue to get bigger, with the average proposed data center doubling in size from about 150 megawatts to 300 megawatts between early 2023 and mid-2024, according to an October 2024 report from Wood Mackenzie.

Even if AI efficiency gains continue, new data centers likely won’t change their plans to use liquid cooling systems, which are more effective at cooling high-powered server racks than traditional air cooling systems, said Angela Taylor, chief of staff at liquid cooling provider LiquidStack. Compass Datacenters says its Chicago-area campus will use non-water liquid cooling, while Microsoft recently unveiled a new closed-loop water cooling system that it said could avoid the need for 125 million liters of water annually at new facilities.

Taylor also expects liquid cooling to play a pivotal role in new inference data centers in “edge” environments closer to users.

“[The] edge has harsh operating and serviceability requirements, such as air pollution, hot and humid climate [and] smaller footprints … liquid cooling shines in these types of environments,” she said.

However, some operators of existing air-cooled data centers may rethink capital-intensive plans to retrofit them with liquid cooling systems, which “are still several years away” from widespread deployment, Nadkarni said.

“[Liquid cooling] is a much heavier lift for retrofits,” he said.

A reset for the power business

Amid long construction time frames and grid interconnection bottlenecks, data center developers like Meta and xAI are racing “to secure as much natural gas as possible,” said Gabriel Kra, managing director at venture capital firm Prelude Ventures.

Entergy Louisiana plans to build three combined-cycle gas plants to power the new Meta campus, while xAI deployed more than a dozen off-grid gas turbines last year while waiting on a grid connection for its Memphis campus.

Over the longer term, the growth of inference data centers “will create a huge need for local availability of electricity in already congested metro areas,” further increasing the value of onsite power, Sridhar said.

But many data centers will still connect to the grid, and more efficient AI models call into question the longer-term economics of premium-priced power deals announced recently, Kra said.

“If the load growth from AI is suddenly curtailed by a factor of five or 10, that has big implications,” Kra said. “We’ve heard recent pitches from companies that are relying on expensive contracts with hyperscalers ….[This] calls those business models more seriously into question.”

On the bright side, lower-than-expected data center energy demand could pay environmental dividends by reducing the need for older coal power plants, Kra added.

Tailwinds for colocation and on-premise compute

If AI models continue to see efficiency gains, then larger enterprises — such as global automakers — may look more closely at bringing more technology development and computing power in-house, rather than relying on third-party resources, Nadkarni said.

That would necessitate capital investment on those companies’ part but could reduce demand for centralized AI computing, he said.

Colocation data centers, where customers rent space to house IT equipment rather than keeping it in their own facilities, are meanwhile “growing extremely fast,” Taylor said.

Colocation facilities tend to be located on highly-connected, adequately powered sites near population centers, making them attractive to users who need computing power in short order, said Scott McCrady, chief client executive at Cologix, a colocation firm. Those located in major network hubs also offer very low-latency computing, which is critical for inference applications from which users expect rapid outputs, he said.

But the tailwinds benefiting on-premise and colocation compute might not be enough to sustain the present data center boom, experts say.

To start, hyperscalers may push for shorter lease terms on large-scale facilities as they weigh uncertainty around future computing power requirements, Leung said.

And the wider industry could be in for a temporary period of overcapacity, similar to what happened in the aftermath of the dot-com boom of the late 1990s and early 2000s, Nadkarni said. It took years for the market to absorb the glut of fiber networks and data centers built back then, he added.

“I have a nagging worry we’re going to see the same thing this time,” Nadkarni said. “I don’t think we can keep building compute at the same rate.”