Intervention needed to support the UK’s nascent green hydrogen industry is at least a year behind schedule, which has resulted in “disappointing” results for the sector.

Statkraft’s vice president of origination for the UK and Ireland called for change to UK policy at an industry event in Glasgow

Speaking on the ‘The Hydrogen Proposition: Make It’ panel at All-Energy, Duncan Dale argued that despite the progress being made in the UK’s hydrogen market, “it’s a little too little and too late” as he added that “we’re about a year behind schedule”.

He added: “The good news is we’re better than Europe, but Europe is a pretty low bar.”

Dale explained that “supply chain cost increases” have also hit the industry, however, “we’re getting better test cases now for electrolysers, which is good”.

The Statkraft UK boss discussed what government needs to do in order to support the UK’s hydrogen sector with his fellow panellists.

© Supplied by Kintore Hydrogen

© Supplied by Kintore HydrogenStatera’s policy manager Phoebe Finn discussed her firm’s massive 3GW Kintore Hydrogen project, which aims to create jobs in the north-east of Scotland.

She called for major changes to the current UK energy system to accommodate hydrogen, including blending the molecule with the gas network and the creation of a dedicated hydrogen transmission system.

‘A critical moment’ for hydrogen in the UK

Finn argued that hydrogen policy needs to “evolve” in order to “unlock projects like Kintore”.

“We’re at a bit of a critical moment where costs need to come down and scale needs to go up and, in my view, the biggest barrier to that is location,” she added.

Location was also a point raised by Dale who argued: “We’ve also got these development road transport fuel certificates as well, but that’s struggling to get going.”

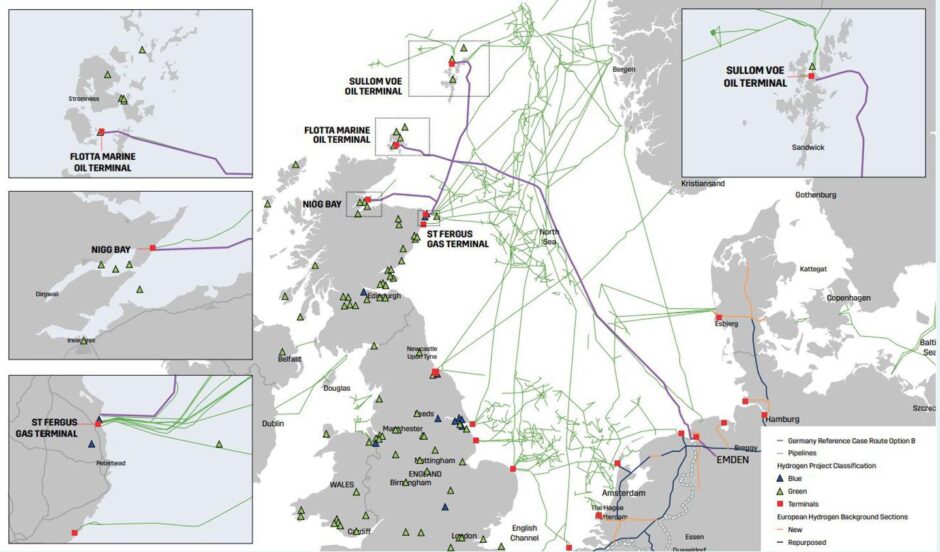

Colocation of hydrogen producer and consumer was a topic that dominated much of All-Energy’s first hydrogen session with Statera advocating for a hydrogen “backbone” pipeline system.

© Supplied by NZTC

© Supplied by NZTCFinn questioned: “So, how do we connect the places where hydrogen can be produced most cheaply, like Scotland, with the places where it’s needed the most?”

In addition to a “dedicated network for hydrogen”, and “a positive decision on blending hydrogen into the existing natural gas transmission network”, Finn said the UK needed “targeted changes to the hydrogen business model to better incentivise flexibility”.

Meeting demand ‘further south’

She pointed out that Scotland is where “renewables are abundant and increasingly being paid to turn off”, however, the location where the electricity is generated is not where the demand lies, “with much of it in the central belt in Scotland and further south,” Finn continued.

“This mismatch is keeping production costs high and preventing hydrogen from playing its most efficient role in our energy transition,” she argued.

The Statera policy manager said that hydrogen stands to play a “critical role” in “balancing our future power system by moving energy across time.”

Finn explained: “What I mean by that is storing renewable power when there is an excess and then using it days or even weeks or months later when there is a shortfall.

“Locating grid-connected electrolysers in Scotland behind electricity constraint boundaries and allowing them to operate flexibly, provides electrolysers with low-cost power, reduces wind curtailment and relieves pressure on the grid.

“But, to unlock the full system value, we need to move the hydrogen to where it’s needed most, and that’s where the hydrogen network comes in.”

Grangemouth and hydrogen

This week, the Scottish Government will discuss the future of hydrogen at the Grangemouth petrochemicals plant which recently shut down Scotland’s last remaining oil refinery.

The Net Zero, Energy and Transport Committee will discuss plans for future of Grangemouth outlined in Project Willow, a report which offered alternative low-carbon options for its continued operations backed by both the Westminster and Holyrood governments.

The Scottish Government group will hear from Statera’s policy director Lewis Elder and representatives from Logan Energy, ScottishPower, PlusZero, and Storegga.

© Andrew Milligan/PA Wire

© Andrew Milligan/PA WireFinn argued: “We need commitment to a hydrogen backbone.

“This would connect key production facilities in Scotland, like Kintore, with storage and with major sources of demand across the UK, such as Grangemouth and Teesside.”

Project Willow suggested three tracks that Grangemouth could take, with two of them involving hydrogen.

In the bio-feedstock track, Grangemouth could convert Scottish cover crops into sustainable aviation fuel and renewable diesel using low-carbon hydrogen, among other things.

The third category was an offshore wind conduit to replace natural gas with hydrogen, using low-carbon hydrogen to produce methanol and convert it to sustainable aviation fuel, and producing low-carbon ammonia from hydrogen for shipping and chemicals.

© Andrew Milligan/PA Wire

© Andrew Milligan/PA WireScottishPower Green Hydrogen’s head of hydrogen market development, Mark Griffin, touched on this at the conference.

“In the UK we have some fantastic locations for the large-scale hydrogen production that don’t naturally sit next to a large industrial cluster and that’s fundamentally where this pipe distribution network or something similar needs to come into place,” he said.

However, the supply chain needs to be taken on the UK’s hydrogen journey if Grangemouth is to see success in these areas.

Griffin commented: “Off the back of Project Willow and the outcome of the report, obviously it talks about gigawatt scale, so we can actually see something that gets you to that scale.

“We need the supply chain to come with us, that’s a huge step from where we are today.”

Zonal pricing and its impact on English colocation

A reliance on colocation of hydrogen producers and users is also called into question by the debate about zonal pricing in the UK.

Zonal pricing will see electricity bills drop where green electricity is produced, and currently, that is primarily in Scotland.

Industry has argued against the measure as some believe that it would make future renewable energy initiatives in Scotland less economically viable.

However, it is a point that must be addressed and one that Dr Kerry-Ann Adamson, vice president and global hydrogen lead for Capgemini, did not shy away from.

“If zonal pricing happens, that means there’s certain areas of the UK which are fundamentally cheaper to produce hydrogen in because it’s cheaper electricity,” she explained.

“That means if they want colocation, we ‘just’ have to move these industrial clusters out the heartland of England and up to, say, the Highlands.”

Dr Adamson added that this is “probably not” something that the UK wants to do.

© Supplied by VPI

© Supplied by VPIShe conceded that the idea of colocation under works for “some markets” such as data centres.

In addition to Grangemouth and the central belt of Scotland, areas including Teesside, the Humber and the north-west of England are also looking to decarbonise heavy industry.

Recently, EET Fuels installed a hydrogen-ready furnace at its Stanlow refinery site, however, since then analysts at Wood Mackenzie have raised concern about how the energy transition is impacting such sites.

It suggested that 101 of the world’s 410 refineries face closure within the next 10 years with those in the UK being particularly affected due to carbon taxes.

© Image: EET Fuels/Sodali

© Image: EET Fuels/SodaliIndustry has called for changes to be made in the UK to support sites like Stanlow which is already investing £1 billion on low carbon hydrogen production and associated carbon capture technologies.

Speaking more generally about UK industrial heartlands, Adamson said: “When you’re talking about industrial clusters, they just need the molecules to decarbonise from wherever it comes from in the UK.

“You’re not going to be able to collocate all the production there to decarbonise it.”