I currently lead a small data team at a small tech company. With everything small, we have a lot of autonomy over what, when, and how we run experiments. In this series, I’m opening the vault from our years of experimenting, each story highlighting a key concept related to experimentation.

And here we’ll share a surprising result from an early test on our referral-bonus program and use it to discuss how you might narrow your decision set for experiments (at least when they involve humans).

Background: It’s COVID and we need to hire a zillion nurses

IntelyCare helps healthcare facilities match with nursing talent. We’re a glorified nurse-recruiting machine and so we’re always looking to recruit more effectively. Nurses come to us from many sources, but those who come via referrals earn higher reviews and stay with us longer.

The year was 2020. IntelyCare was a baby company (still is by most standards). Our app was new and most features were still primitive. Some examples…

- We had a way for IntelyPros to share a referral link with friends but had no financial incentives to do so.

- Our application process was a major slog. We required a small mountain of documents for review in addition to a phone interview and references. Only a small subset of applicants made it all the way through to working.

During a recruiting brainstorm, we latched onto the idea of referrals and agreed that adding financial incentives would be easy to test. Something like, “Get $100 when your friend starts working.” Zero creativity there, but an idea doesn’t have to be novel to be good.

Knowing that many people might refer again and again if they earned a bonus, and knowing that our application process was nothing short of a gauntlet, we also wondered if it might be better instead to give clinicians a small prize when their friends start an application.

A small prize for something easy vs a big prize for something difficult? I mean, it depends on many things. There’s only one way to know which is best, and that’s to try them out.

The referral test

We randomly assigned clinicians to one of two experiences:

- The clinician earns an extra $1/hour on their next shift when their referral starts a job application. (Super easy. Starting an application takes 1–2 minutes.)

- The clinician earns $100 when their referral completes their first shift. (Super hard. Some nurses race through it, but most applicants take several weeks or even months if they finish at all).

We held out an equal third of clinicians as a control and let clinicians know the rules via a series of emails. There’s always a risk of spillovers in a test like this, but the thought of one group stealing all the referrals from the other group seemed like a stretch, so we felt good about randomizing across individuals.

Decidedly non-social: Many people hear these two options and ask, “Did you think of trying prosocial incentives?” (Example: I refer you, you do something, we both get a prize). Studies show they’re often better than individual incentives and they’re quite common (instacart, airbnb, robinhood,…). We considered these, but our finance team became very sad at the idea of us sending $1 each to hundreds of people who may not ever become employees.

I guess Quickbooks doesn’t like that? At some point, you just accept that it’s best to not mess with the finance team.

Since the $1/hr reward could not be prosocial without becoming a major headache, we limited payouts in both programs to the referring individual only. This gives us two referral programs where the key differences are timing and the payout amount.

Turns out timing and presentation of incentives matter. A lot. Social incentives also matter. A lot. If you’re trying to growth-hack your referral program, you would be smart to consider both of these dimensions before increasing the payout.

Nerdy aside: Thinking about things to test

Product data science, with minimal exception, is interested in how humans interact with things. Often it’s a website or an app, but it could be a physical object like a pair of headphones, a thermostat, or a sign on the highway.

The science comes from changing the product and watching how humans change their behavior as a result. And you can’t do better than watching your customers interact with your product in the wild to learn whether a change was helpful or not.

But you can’t test everything. There are infinite things to test and any group tasked with experimenting will have to cut things down to a finite set of ideas. Where do you start?

- Start with the product itself. Ask people who are familiar with it how they like it, what they wish was different, Sean Ellis, NPS, the Mom Test, etc. This is the common starting point for product teams and just about everyone else.

- Start with human nature. For many decades Behavioral Scientists have documented particular patterns in human behavior. These scientists go by different names (behavioral economists, behavioral psychologists, etc.).

In my humble opinion, the 2nd of these starting points is severely underrated. Behavioral science has documented dozens of behavior patterns that can inform how your product might change most effectively.

A few honorable mentions…

- Loss aversion: people hate losing more than they like winning

- Peak-End: people remember things more favorably when they end on a positive note

- Social vs Market Norms: everything changes when people pay for goods and services instead of asking for favors

- Framing: people make choices based on how information is presented

- Left-digit Bias: perceptions of a price are disproportionately influenced by the leading digit ($0.99 = 🔥, $1.01 = 🥱)

- Present Bias: people hate waiting

These mental shortcuts aren’t a silver bullet for product and Marketing. We’ve tested many of these in different settings to no effect, but some have worked. Maybe you’ll find $160M under your couch cushions.

Zooming in on present bias

Many humans demonstrate a behavior pattern where they prefer small, immediate rewards over larger rewards in the future. Social scientists call this present bias and measure it with tough questions like…

People who choose immediate, smaller rewards have some measure of present bias.

Present bias can vary across people and circumstances. You could be a patient person in most situations. But when you’re hungry or tired… not so much. This is one reason why A/B tests are so useful compared to, say, surveys or interviews.

For our experiment, the question is not so different from the lab questions:

- Would you rather have ~$8 sometime this week or $100 sometime in the coming weeks and maybe never?

Experiment results

Many of us (present company included) thought the $100 offer would do best. It sounds bigger. It looks better in an email. It’s easy to explain.

I also thought we might get more applications from referrals with the $1/hr program, but didn’t think that would carry through to more referrals. I figured people would take the money and run.

To my surprise the $1/hr program delivered more applications via referrals and more working clinicians, all at a much lower cost.

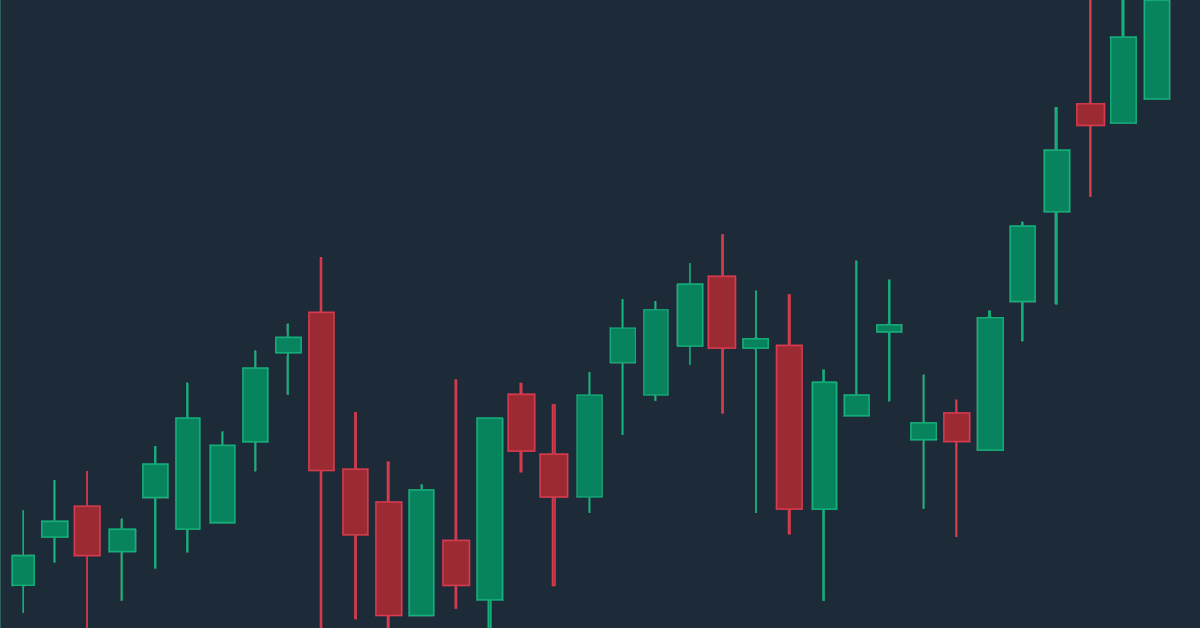

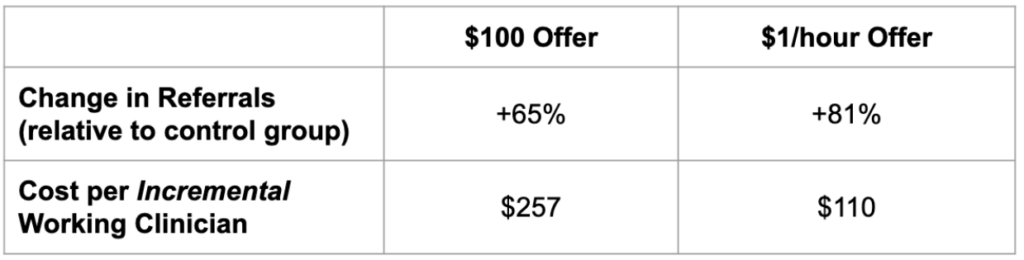

The $100 offer led to a 65% increase in referrals compared to our control group. This is huge!. Many people like this type of program because we’re only giving rewards when a referral is successful. It feels like the money is well spent.

The $1/hr offer, however, is even better. Referrals increased by 81% compared to our control group. And even though the rewards were smaller and paid out earlier, referrals from these IntelyPros still went on to start working for us at about the same rate as the $100 group.

Yes, many IntelyPros earned rewards for referrals that applied and then failed to cross the finish line, but the math still worked out. Even with an imperfect conversion rate from application to working, the total cost per new working IntelyPro was less than half of the $100 group’s cost.

ABT: Always be testing

The role that referrals play for a business can change for many reasons. As a company becomes bigger and more familiar, referrals become less important. You don’t need people to spread the word because the word is already out.

We ran this test in 2020 during a global pandemic. We ran a smaller-scale test a year later and saw similar results. Would we see the same results now, in 2025? Hard to say. Things are much different in the healthcare staffing space nowadays.

This is yet another reason why testing is so important. Something like referral bonuses could work wonders for company A while being a dud for company B. The upside of product experiments is that the world is your laboratory. The downside is that it’s hard to know what generalizes to other products.

Key takeaways for those who made it this far

- When you’re running experiments to improve your product and collect data from the humans using your product, behavioral science is a fruitful place to look for test ideas.

- Sometimes the ideas that seem less great turn out to have the highest impact!

- Timing and presentation matter for incentives. Before you increase the size of some payout, perhaps put some thought into the time and effort required to earn that payout.

(This post was refurbished from my own 2022 post on behavioraleconomics.com)