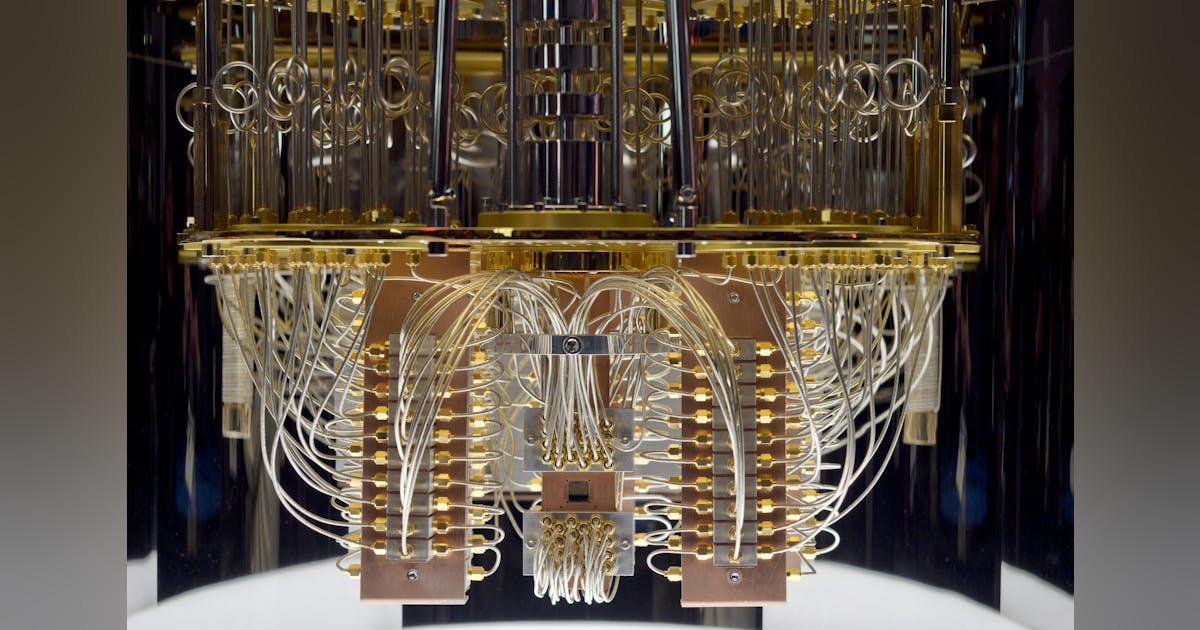

In this era of AI slop, the idea that generative AI tools like Midjourney and Runway could be used to make art can seem absurd: What possible artistic value is there to be found in the likes of Shrimp Jesus and Ballerina Cappuccina? But amid all the muck, there are people using AI tools with real consideration and intent. Some of them are finding notable success as AI artists: They are gaining huge online followings, selling their work at auction, and even having it exhibited in galleries and museums.

“Sometimes you need a camera, sometimes AI, and sometimes paint or pencil or any other medium,” says Jacob Adler, a musician and composer who won the top prize at the generative video company Runway’s third annual AI Film Festival for his work Total Pixel Space. “It’s just one tool that is added to the creator’s toolbox.”

One of the most conspicuous features of generative AI tools is their accessibility. With no training and in very little time, you can create an image of whatever you can imagine in whatever style you desire. That’s a key reason AI art has attracted so much criticism: It’s now trivially easy to clog sites like Instagram and TikTok with vapid nonsense, and companies can generate images and video themselves instead of hiring trained artists.

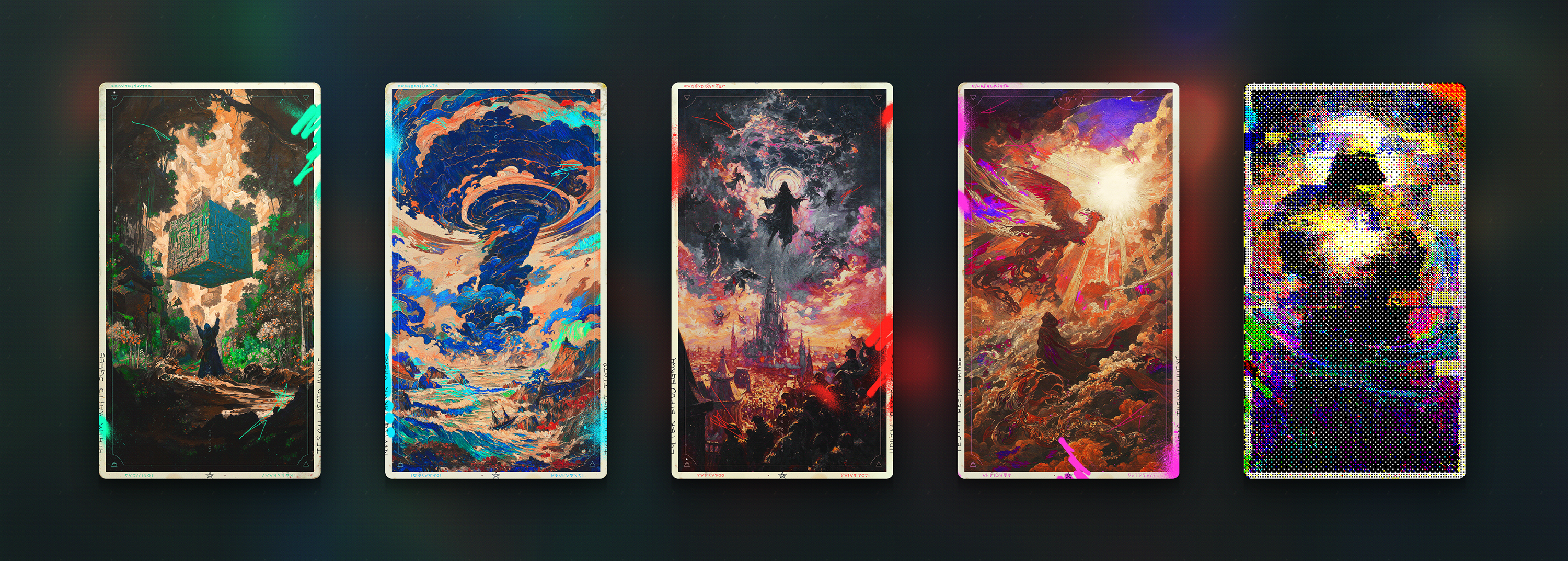

Henry Daubrez, an artist and designer who created the AI-generated visuals for a bitcoin NFT that sold for $24,000 at Sotheby’s and is now Google’s first filmmaker in residence, sees that accessibility as one of generative AI’s most positive attributes. People who had long since given up on creative expression, or who simply never had the time to master a medium, are now creating and sharing art, he says.

But that doesn’t mean the first AI-generated masterpiece could come from just anyone. “I don’t think [generative AI] is going to create an entire generation of geniuses,” says Daubrez, who has described himself as an “AI-assisted artist.” Prompting tools like DALL-E and Midjourney might not require technical finesse, but getting those tools to create something interesting, and then evaluating whether the results are any good, takes both imagination and artistic sensibility, he says: “I think we’re getting into a new generation which is going to be driven by taste.”

Even for artists who do have experience with other media, AI can be more than just a shortcut. Beth Frey, a trained fine artist who shares her AI art on an Instagram account with over 100,000 followers, was drawn to early generative AI tools because of the uncanniness of their creations—she relished the deformed hands and haunting depictions of eating. Over time, the models’ errors have been ironed out, which is part of the reason she hasn’t posted an AI-generated piece on Instagram in over a year. “The better it gets, the less interesting it is for me,” she says. “You have to work harder to get the glitch now.”

Making art with AI can require relinquishing control—to the companies that update the tools, and to the tools themselves. For Kira Xonorika, a self-described “AI-collaborative artist” whose short film Trickster is the first generative AI piece in the Denver Art Museum’s permanent collection, that lack of control is part of the appeal. “[What] I really like about AI is the element of unpredictability,” says Xonorika, whose work explores themes such as indigeneity and nonhuman intelligence. “If you’re open to that, it really enhances and expands ideas that you might have.”

But the idea of AI as a co-creator—or even simply as an artistic medium—is still a long way from widespread acceptance. To many people, “AI art” and “AI slop” remain synonymous. And so, as grateful as Daubrez is for the recognition he has received so far, he’s found that pioneering a new form of art in the face of such strong opposition is an emotional mixed bag. “As long as it’s not really accepted that AI is just a tool like any other tool and people will do whatever they want with it—and some of it might be great, some might not be—it’s still going to be sweet [and] sour,” he says.