Sometimes Lizzie Wilson shows up to a rave with her AI sidekick.

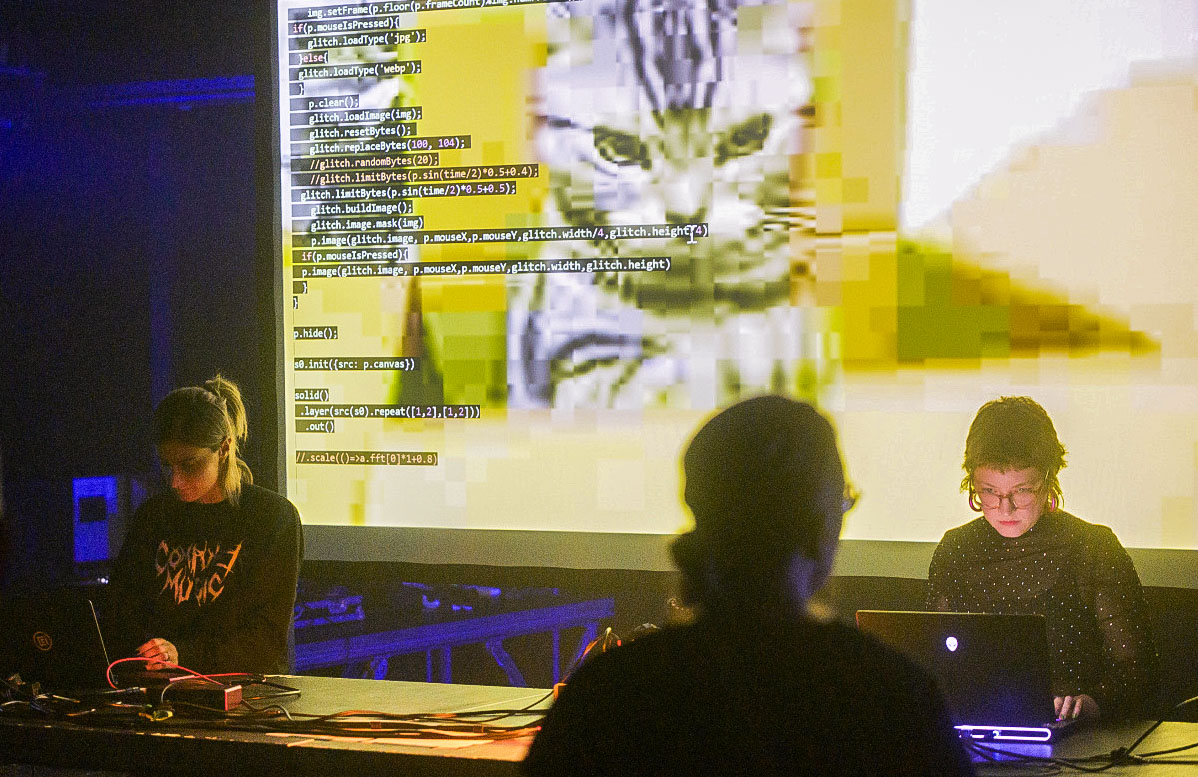

One weeknight this past February, Wilson plugged her laptop into a projector that threw her screen onto the wall of a low-ceilinged loft space in East London. A small crowd shuffled in the glow of dim pink lights. Wilson sat down and started programming.

Techno clicks and whirs thumped from the venue’s speakers. The audience watched, heads nodding, as Wilson tapped out code line by line on the projected screen—tweaking sounds, looping beats, pulling a face when she messed up.

Wilson is a live coder. Instead of using purpose-built software like most electronic music producers, live coders create music by writing the code to generate it on the fly. It’s an improvised performance art known as algorave.

“It’s kind of boring when you go to watch a show and someone’s just sitting there on their laptop,” she says. “You can enjoy the music, but there’s a performative aspect that’s missing. With live coding, everyone can see what it is that I’m typing. And when I’ve had my laptop crash, people really like that. They start cheering.”

Taking risks is part of the vibe. And so Wilson likes to dial up her performances one more notch by riffing off what she calls a live-coding agent, a generative AI model that comes up with its own beats and loops to add to the mix. Often the model suggests sound combinations that Wilson hadn’t thought of. “You get these elements of surprise,” she says. “You just have to go for it.”

Wilson, a researcher at the Creative Computing Institute at the University of the Arts London, is just one of many working on what’s known as co-creativity or more-than-human creativity. The idea is that AI can be used to inspire or critique creative projects, helping people make things that they would not have made by themselves. She and her colleagues built the live-coding agent to explore how artificial intelligence can be used to support human artistic endeavors—in Wilson’s case, musical improvisation.

It’s a vision that goes beyond the promise of existing generative tools put out by companies like OpenAI and Google DeepMind. Those can automate a striking range of creative tasks and offer near-instant gratification—but at what cost? Some artists and researchers fear that such technology could turn us into passive consumers of yet more AI slop.

And so they are looking for ways to inject human creativity back into the process. The aim is to develop AI tools that augment our creativity rather than strip it from us—pushing us to be better at composing music, developing games, designing toys, and much more—and lay the groundwork for a future in which humans and machines create things together.

Ultimately, generative models could offer artists and designers a whole new medium, pushing them to make things that couldn’t have been made before, and give everyone creative superpowers.

Explosion of creativity

There’s no one way to be creative, but we all do it. We make everything from memes to masterpieces, infant doodles to industrial designs. There’s a mistaken belief, typically among adults, that creativity is something you grow out of. But being creative—whether cooking, singing in the shower, or putting together super-weird TikToks—is still something that most of us do just for the fun of it. It doesn’t have to be high art or a world-changing idea (and yet it can be). Creativity is basic human behavior; it should be celebrated and encouraged.

When generative text-to-image models like Midjourney, OpenAI’s DALL-E, and the popular open-source Stable Diffusion arrived, they sparked an explosion of what looked a lot like creativity. Millions of people were now able to create remarkable images of pretty much anything, in any style, with the click of a button. Text-to-video models came next. Now startups like Udio are developing similar tools for music. Never before have the fruits of creation been within reach of so many.

But for a number of researchers and artists, the hype around these tools has warped the idea of what creativity really is. “If I ask the AI to create something for me, that’s not me being creative,” says Jeba Rezwana, who works on co-creativity at Towson University in Maryland. “It’s a one-shot interaction: You click on it and it generates something and that’s it. You cannot say ‘I like this part, but maybe change something here.’ You cannot have a back-and-forth dialogue.”

Rezwana is referring to the way most generative models are set up. You can give the tools feedback and ask them to have another go. But each new result is generated from scratch, which can make it hard to nail exactly what you want. As the filmmaker Walter Woodman put it last year after his art collective Shy Kids made a short film with OpenAI’s text-to-video model for the first time: “Sora is a slot machine as to what you get back.”

What’s more, the latest versions of some of these generative tools do not even use your submitted prompt as is to produce an image or video (at least not on their default settings). Before a prompt is sent to the model, the software edits it—often by adding dozens of hidden words—to make it more likely that the generated image will appear polished.

“Extra things get added to juice the output,” says Mike Cook, a computational creativity researcher at King’s College London. “Try asking Midjourney to give you a bad drawing of something—it can’t do it.” These tools do not give you what you want; they give you what their designers think you want.

All of which is fine if you just need a quick image and don’t care too much about the details, says Nick Bryan-Kinns, also at the Creative Computing Institute: “Maybe you want to make a Christmas card for your family or a flyer for your community cake sale. These tools are great for that.”

In short, existing generative models have made it easy to create, but they have not made it easy to be creative. And there’s a big difference between the two. For Cook, relying on such tools could in fact harm people’s creative development in the long run. “Although many of these creative AI systems are promoted as making creativity more accessible,” he wrote in a paper published last year, they might instead have “adverse effects on their users in terms of restricting their ability to innovate, ideate, and create.” Given how much generative models have been championed for putting creative abilities at everyone’s fingertips, the suggestion that they might in fact do the opposite is damning.

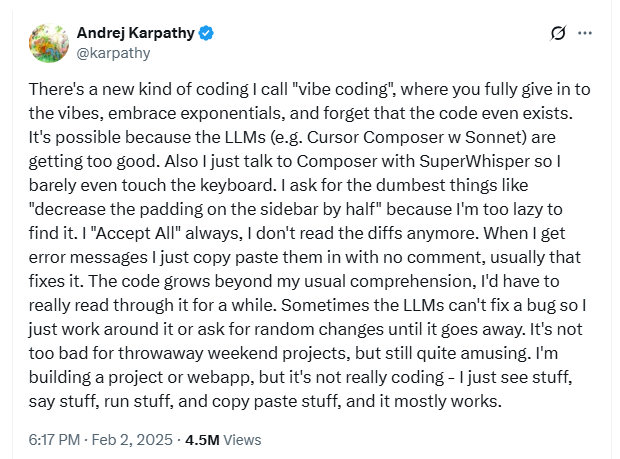

He’s far from the only researcher worrying about the cognitive impact of these technologies. In February a team at Microsoft Research Cambridge published a report concluding that generative AI tools “can inhibit critical engagement with work and can potentially lead to long-term overreliance on the tool and diminished skill for independent problem-solving.” The researchers found that with the use of generative tools, people’s effort “shifts from task execution to task stewardship.”

Cook is concerned that generative tools don’t let you fail—a crucial part of learning new skills. We have a habit of saying that artists are gifted, says Cook. But the truth is that artists work at their art, developing skills over months and years.

“If you actually talk to artists, they say, ‘Well, I got good by doing it over and over and over,’” he says. “But failure sucks. And we’re always looking at ways to get around that.”

Generative models let us skip the frustration of doing a bad job.

“Unfortunately, we’re removing the one thing that you have to do to develop creative skills for yourself, which is fail,” says Cook. “But absolutely nobody wants to hear that.”

Surprise me

And yet it’s not all bad news. Artists and researchers are buzzing at the ways generative tools could empower creators, pointing them in surprising new directions and steering them away from dead ends. Cook thinks the real promise of AI will be to help us get better at what we want to do rather than doing it for us. For that, he says, we’ll need to create new tools, different from the ones we have now. “Using Midjourney does not do anything for me—it doesn’t change anything about me,” he says. “And I think that’s a wasted opportunity.”

Ask a range of researchers studying creativity to name a key part of the creative process and many will say: reflection. It’s hard to define exactly, but reflection is a particular type of focused, deliberate thinking. It’s what happens when a new idea hits you. Or when an assumption you had turns out to be wrong and you need to rethink your approach. It’s the opposite of a one-shot interaction.

Looking for ways that AI might support or encourage reflection—asking it to throw new ideas into the mix or challenge ideas you already hold—is a common thread across co-creativity research. If generative tools like DALL-E make creation frictionless, the aim here is to add friction back in. “How can we make art without friction?” asks Elisa Giaccardi, who studies design at the Polytechnic University of Milan in Italy. “How can we engage in a truly creative process without material that pushes back?”

Take Wilson’s live-coding agent. She claims that it pushes her musical improvisation in directions she might not have taken by herself. Trained on public code shared by the wider live-coding community, the model suggests snippets of code that are closer to other people’s styles than her own. This makes it more likely to produce something unexpected. “Not because you couldn’t produce it yourself,” she says. “But the way the human brain works, you tend to fall back on repeated ideas.”

Last year, Wilson took part in a study run by Bryan-Kinns and his colleagues in which they surveyed six experienced musicians as they used a variety of generative models to help them compose a piece of music. The researchers wanted to get a sense of what kinds of interactions with the technology were useful and which were not.

The participants all said they liked it when the models made surprising suggestions, even when those were the result of glitches or mistakes. Sometimes the results were simply better. Sometimes the process felt fresh and exciting. But a few people struggled with giving up control. It was hard to direct the models to produce specific results or to repeat results that the musicians had liked. “In some ways it’s the same as being in a band,” says Bryan-Kinns. “You need to have that sense of risk and a sense of surprise, but you don’t want it totally random.”

Alternative designs

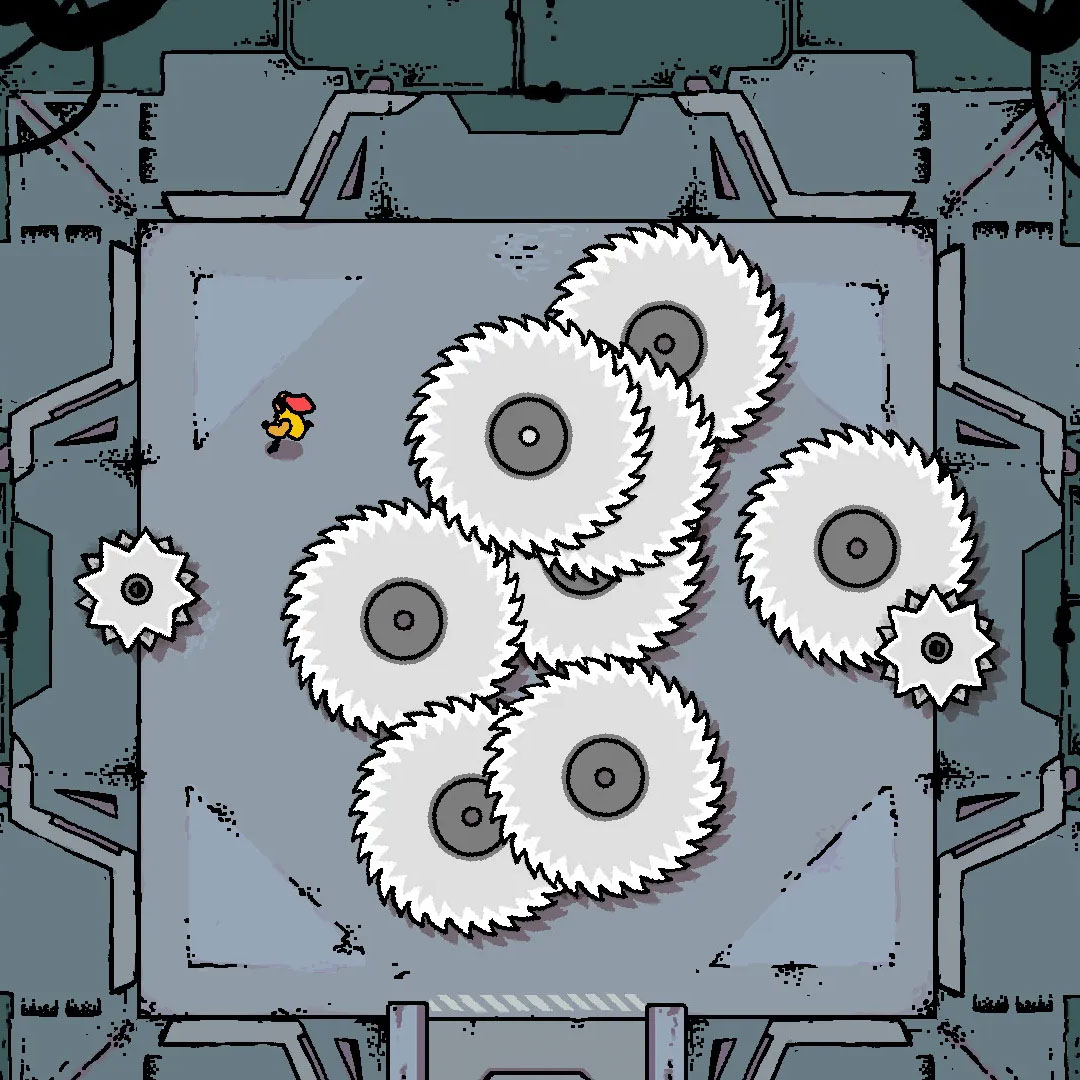

Cook comes at surprise from a different angle: He coaxes unexpected insights out of AI tools that he has developed to co-create video games. One of his tools, Puck, which was first released in 2022, generates designs for simple shape-matching puzzle games like Candy Crush or Bejeweled. A lot of Puck’s designs are experimental and clunky—don’t expect it to come up with anything you are ever likely to play. But that’s not the point: Cook uses Puck—and a newer tool called Pixie—to explore what kinds of interactions people might want to have with a co-creative tool.

Pixie can read computer code for a game and tweak certain lines to come up with alternative designs. Not long ago, Cook was working on a copy of a popular game called Disc Room, in which players have to cross a room full of moving buzz saws. He asked Pixie to help him come up with a design for a level that skilled and unskilled players would find equally hard. Pixie designed a room where none of the discs actually moved. Cook laughs: It’s not what he expected. “It basically turned the room into a minefield,” he says. “But I thought it was really interesting. I hadn’t thought of that before.”

Researcher Anne Arzberger developed experimental AI tools to come up with gender-neutral toy designs.

Pushing back on assumptions, or being challenged, is part of the creative process, says Anne Arzberger, a researcher at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. “If I think of the people I’ve collaborated with best, they’re not the ones who just said ‘Yes, great’ to every idea I brought forth,” she says. “They were really critical and had opposing ideas.”

She wants to build tech that provides a similar sounding board. As part of a project called Creating Monsters, Arzberger developed two experimental AI tools that help designers find hidden biases in their designs. “I was interested in ways in which I could use this technology to access information that would otherwise be difficult to access,” she says.

For the project, she and her colleagues looked at the problem of designing toy figures that would be gender neutral. She and her colleagues (including Giaccardi) used Teachable Machine, a web app built by Google researchers in 2017 that makes it easy to train your own machine-learning model to classify different inputs, such as images. They trained this model with a few dozen images that Arzberger had labeled as being masculine, feminine, or gender neutral.

Arzberger then asked the model to identify the genders of new candidate toy designs. She found that quite a few designs were judged to be feminine even when she had tried to make them gender neutral. She felt that her views of the world—her own hidden biases—were being exposed. But the tool was often right: It challenged her assumptions and helped the team improve the designs. The same approach could be used to assess all sorts of design characteristics, she says.

Arzberger then used a second model, a version of a tool made by the generative image and video startup Runway, to come up with gender-neutral toy designs of its own. First the researchers trained the model to generate and classify designs for male- and female-looking toys. They could then ask the tool to find a design that was exactly midway between the male and female designs it had learned.

Generative models can give feedback on designs that human designers might miss by themselves, she says: “We can really learn something.”

Taking control

The history of technology is full of breakthroughs that changed the way art gets made, from recipes for vibrant new paint colors to photography to synthesizers. In the 1960s, the Stanford researcher John Chowning spent years working on an esoteric algorithm that could manipulate the frequencies of computer-generated sounds. Stanford licensed the tech to Yamaha, which built it into its synthesizers—including the DX7, the cool new sound behind 1980s hits such as Tina Turner’s “The Best,” A-ha’s “Take On Me,” and Prince’s “When Doves Cry.”

Bryan-Kinns is fascinated by how artists and designers find ways to use new technologies. “If you talk to artists, most of them don’t actually talk about these AI generative models as a tool—they talk about them as a material, like an artistic material, like a paint or something,” he says. “It’s a different way of thinking about what the AI is doing.” He highlights the way some people are pushing the technology to do weird things it wasn’t designed to do. Artists often appropriate or misuse these kinds of tools, he says.

Bryan-Kinns points to the work of Terence Broad, another colleague of his at the Creative Computing Institute, as a favorite example. Broad employs techniques like network bending, which involves inserting new layers into a neural network to produce glitchy visual effects in generated images, and generating images with a model trained on no data, which produces almost Rothko-like abstract swabs of color.

But Broad is an extreme case. Bryan-Kinns sums it up like this: “The problem is that you’ve got this gulf between the very commercial generative tools that produce super-high-quality outputs but you’ve got very little control over what they do—and then you’ve got this other end where you’ve got total control over what they’re doing but the barriers to use are high because you need to be somebody who’s comfortable getting under the hood of your computer.”

“That’s a small number of people,” he says. “It’s a very small number of artists.”

Arzberger admits that working with her models was not straightforward. Running them took several hours, and she’s not sure the Runway tool she used is even available anymore. Bryan-Kinns, Arzberger, Cook, and others want to take the kinds of creative interactions they are discovering and build them into tools that can be used by people who aren’t hardcore coders.

Researcher Terence Broad creates dynamic images using a model trained on no data, which produces almost Rothko-like abstract color fields.

Finding the right balance between surprise and control will be hard, though. Midjourney can surprise, but it gives few levers for controlling what it produces beyond your prompt. Some have claimed that writing prompts is itself a creative act. “But no one struggles with a paintbrush the way they struggle with a prompt,” says Cook.

Faced with that struggle, Cook sometimes watches his students just go with the first results a generative tool gives them. “I’m really interested in this idea that we are priming ourselves to accept that whatever comes out of a model is what you asked for,” he says. He is designing an experiment that will vary single words and phrases in similar prompts to test how much of a mismatch people see between what they expect and what they get.

But it’s early days yet. In the meantime, companies developing generative models typically emphasize results over process. “There’s this impressive algorithmic progress, but a lot of the time interaction design is overlooked,” says Rezwana.

For Wilson, the crucial choice in any co-creative relationship is what you do with what you’re given. “You’re having this relationship with the computer that you’re trying to mediate,” she says. “Sometimes it goes wrong, and that’s just part of the creative process.”

When AI gives you lemons—make art. “Wouldn’t it be fun to have something that was completely antagonistic in a performance—like, something that is actively going against you—and you kind of have an argument?” she says. “That would be interesting to watch, at least.”