Americans don’t agree on much these days. Yet even at a time when consensus reality seems to be on the verge of collapse, there remains at least one quintessentially modern value we can all still get behind: creativity.

We teach it, measure it, envy it, cultivate it, and endlessly worry about its death. And why wouldn’t we? Most of us are taught from a young age that creativity is the key to everything from finding personal fulfillment to achieving career success to solving the world’s thorniest problems. Over the years, we’ve built creative industries, creative spaces, and creative cities and populated them with an entire class of people known simply as “creatives.” We read thousands of books and articles each year that teach us how to unleash, unlock, foster, boost, and hack our own personal creativity. Then we read even more to learn how to manage and protect this precious resource.

Given how much we obsess over it, the concept of creativity can feel like something that has always existed, a thing philosophers and artists have pondered and debated throughout the ages. While it’s a reasonable assumption, it’s one that turns out to be very wrong. As Samuel Franklin explains in his recent book, The Cult of Creativity, the first known written use of creativity didn’t actually occur until 1875, “making it an infant as far as words go.” What’s more, he writes, before about 1950, “there were approximately zero articles, books, essays, treatises, odes, classes, encyclopedia entries, or anything of the sort dealing explicitly with the subject of ‘creativity.’”

This raises some obvious questions. How exactly did we go from never talking about creativity to always talking about it? What, if anything, distinguishes creativity from other, older words, like ingenuity, cleverness, imagination, and artistry? Maybe most important: How did everyone from kindergarten teachers to mayors, CEOs, designers, engineers, activists, and starving artists come to believe that creativity isn’t just good—personally, socially, economically—but the answer to all life’s problems?

Thankfully, Franklin offers some potential answers in his book. A historian and design researcher at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, he argues that the concept of creativity as we now know it emerged during the post–World War II era in America as a kind of cultural salve—a way to ease the tensions and anxieties caused by increasing conformity, bureaucracy, and suburbanization.

“Typically defined as a kind of trait or process vaguely associated with artists and geniuses but theoretically possessed by anyone and applicable to any field, [creativity] provided a way to unleash individualism within order,” he writes, “and revive the spirit of the lone inventor within the maze of the modern corporation.”

I spoke to Franklin about why we continue to be so fascinated by creativity, how Silicon Valley became the supposed epicenter of it, and what role, if any, technologies like AI might have in reshaping our relationship with it.

I’m curious what your personal relationship to creativity was growing up. What made you want to write a book about it?

Like a lot of kids, I grew up thinking that creativity was this inherently good thing. For me—and I imagine for a lot of other people who, like me, weren’t particularly athletic or good at math and science—being creative meant you at least had some future in this world, even if it wasn’t clear what that future would entail. By the time I got into college and beyond, the conventional wisdom among the TED Talk register of thinkers—people like Daniel Pink and Richard Florida—was that creativity was actually the most important trait to have for the future. Basically, the creative people were going to inherit the Earth, and society desperately needed them if we were going to solve all of these compounding problems in the world.

On the one hand, as someone who liked to think of himself as creative, it was hard not to be flattered by this. On the other hand, it all seemed overhyped to me. What was being sold as the triumph of the creative class wasn’t actually resulting in a more inclusive or creative world order. What’s more, some of the values embedded in what I call the cult of creativity seemed increasingly problematic—specifically, the focus on self-realization, doing what you love, and following your passion. Don’t get me wrong—it’s a beautiful vision, and I saw it work out for some people. But I also started to feel like it was just a cover for what was, economically speaking, a pretty bad turn of events for many people.

Nowadays, it’s quite common to bash the “follow your passion,” “hustle culture” idea. But back when I started this project, the whole move-fast-and-break-things, disrupter, innovation-economy stuff was very much unquestioned. In a way, the idea for the book came from recognizing that creativity was playing this really interesting role in connecting two worlds: this world of innovation and entrepreneurship and this more soulful, bohemian side of our culture. I wanted to better understand the history of that relationship.

When did you start thinking about creativity as a kind of cult—one that we’re all a part of?

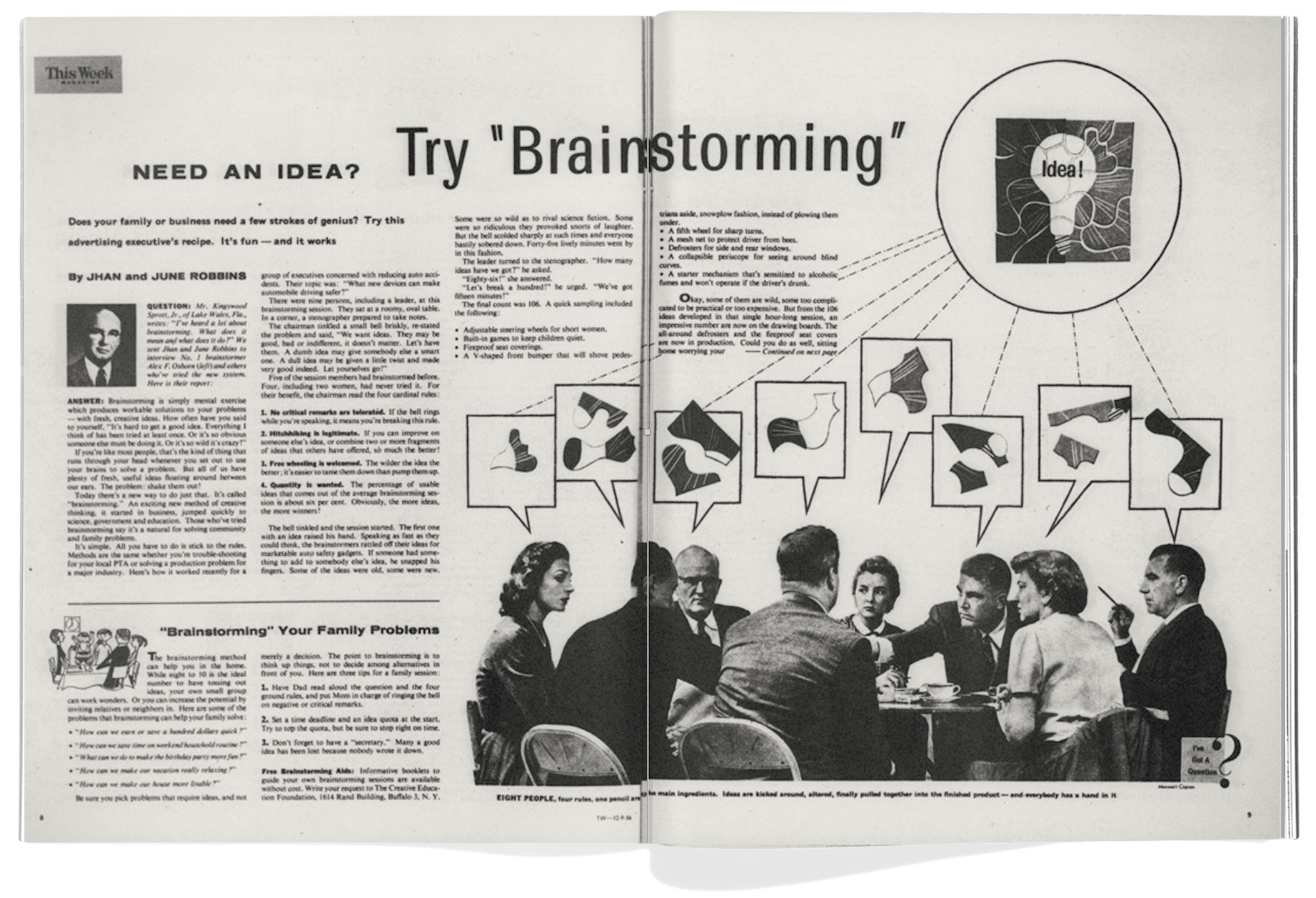

Similar to something like the “cult of domesticity,” it was a way of describing a historical moment in which an idea or value system achieves a kind of broad, uncritical acceptance. I was finding that everyone was selling stuff based on the idea that it boosted your creativity, whether it was a new office layout, a new kind of urban design, or the “Try these five simple tricks” type of thing.

You start to realize that nobody is bothering to ask, “Hey, uh, why do we all need to be creative again? What even is this thing, creativity?” It had become this unimpeachable value that no one, regardless of what side of the political spectrum they fell on, would even think to question. That, to me, was really unusual, and I think it signaled that something interesting was happening.

Your book highlights midcentury efforts by psychologists to turn creativity into a quantifiable mental trait and the “creative person” into an identifiable type. How did that play out?

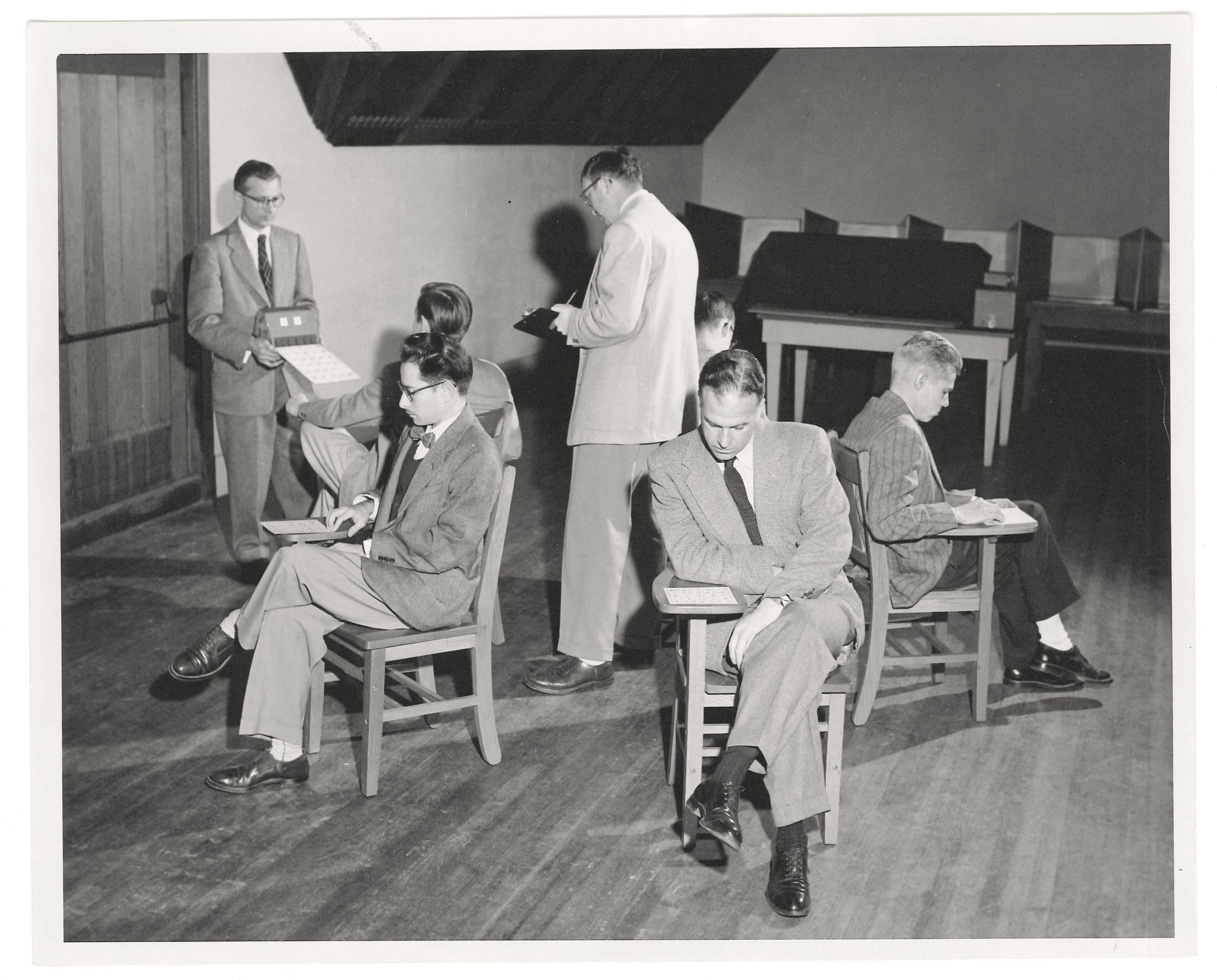

The short answer is: not very well. To study anything, you of course need to agree on what it is you’re looking at. Ultimately, I think these groups of psychologists were frustrated in their attempts to come up with scientific criteria that defined a creative person. One technique was to go find people who were already eminent in fields that were deemed creative—writers like Truman Capote and Norman Mailer, architects like Louis Kahn and Eero Saarinen—and just give them a battery of cognitive and psychoanalytic tests and then write up the results. This was mostly done by an outfit called the Institute of Personality Assessment and Research (IPAR) at Berkeley. Frank Barron and Don MacKinnon were the two biggest researchers in that group.

Another way psychologists went about it was to say, all right, that’s not going to be practical for coming up with a good scientific standard. We need numbers, and lots and lots of people to certify these creative criteria. This group of psychologists theorized that something called “divergent thinking” was a major component of creative accomplishment. You’ve heard of the brick test, where you’re asked to come up with many creative uses for a brick in a given amount of time? They basically gave a version of that test to Army officers, schoolchildren, rank-and-file engineers at General Electric, all kinds of people. It’s tests like those that ultimately became stand-ins for what it means to be “creative.”

Are they still used?

When you see a headline about AI making people more creative, or actually being more creative than humans, the tests they are basing that assertion on are almost always some version of a divergent thinking test. It’s highly problematic for a number of reasons. Chief among them is the fact that these tests have never been shown to have predictive value—that’s to say, a third grader, a 21-year-old, or a 35-year-old who does really well on divergent thinking tests doesn’t seem to have any greater likelihood of being successful in creative pursuits. The whole point of developing these tests in the first place was to both identify and predict creative people. None of them have been shown to do that.

Reading your book, I was struck by how vague and, at times, contradictory the concept of “creativity” was from the beginning. You characterize that as “a feature, not a bug.” How so?

Ask any creativity expert today what they mean by “creativity,” and they’ll tell you it’s the ability to generate something new and useful. That something could be an idea, a product, an academic paper—whatever. But the focus on novelty has remained an aspect of creativity from the beginning. It’s also what distinguishes it from other similar words, like imagination or cleverness. But you’re right: Creativity is a flexible enough concept to be used in all sorts of ways and to mean all sorts of things, many of them contradictory. I think I write in the book that the term may not be precise, but that it’s vague in precise and meaningful ways. It can be both playful and practical, artsy and technological, exceptional and pedestrian. That was and remains a big part of its appeal.

The question of “Can machines be ‘truly creative’?” is not that interesting, but the questions of “Can they be wise, honest, caring?” are more important if we’re going to be welcoming [AI] into our lives as advisors and assistants.

Is that emphasis on novelty and utility a part of why Silicon Valley likes to think of itself as the new nexus for creativity?

Absolutely. The two criteria go together. In techno-solutionist, hypercapitalist milieus like Silicon Valley, novelty isn’t any good if it’s not useful (or at least marketable), and utility isn’t any good (or marketable) unless it’s also novel. That’s why they’re often dismissive of boring-but-important things like craft, infrastructure, maintenance, and incremental improvement, and why they support art—which is traditionally defined by its resistance to utility—only insofar as it’s useful as inspiration for practical technologies.

At the same time, Silicon Valley loves to wrap itself in “creativity” because of all the artsy and individualist connotations. It has very self-consciously tried to distance itself from the image of the buttoned-down engineer working for a large R&D lab of a brick-and-mortar manufacturing corporation and instead raise up the idea of a rebellious counterculture type tinkering in a garage making weightless products and experiences. That, I think, has saved it from a lot of public scrutiny.

Up until recently, we’ve tended to think of creativity as a human trait, maybe with a few exceptions from the rest of the animal world. Is AI changing that?

When people started defining creativity in the ’50s, the threat of computers automating white-collar work was already underway. They were basically saying, okay, rational and analytical thinking is no longer ours alone. What can we do that the computers can never do? And the assumption was that humans alone could be “truly creative.” For a long time, computers didn’t do much to really press the issue on what that actually meant. Now they’re pressing the issue. Can they do art and poetry? Yes. Can they generate novel products that also make sense or work? Sure.

I think that’s by design. The kinds of LLMs that Silicon Valley companies have put forward are meant to appear “creative” in those conventional senses. Now, whether or not their products are meaningful or wise in a deeper sense, that’s another question. If we’re talking about art, I happen to think embodiment is an important element. Nerve endings, hormones, social instincts, morality, intellectual honesty—those are not things essential to “creativity” necessarily, but they are essential to putting things out into the world that are good, and maybe even beautiful in a certain antiquated sense. That’s why I think the question of “Can machines be ‘truly creative’?” is not that interesting, but the questions of “Can they be wise, honest, caring?” are more important if we’re going to be welcoming them into our lives as advisors and assistants.

This interview is based on two conversations and has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Bryan Gardiner is a writer based in Oakland, California.