Opinion

These tariffs were designed to offer large loads access to renewable energy, but they could be expanded to baseload generation to remove at-risk generation from the utility’s books.

Published June 5, 2025

By

Ben Hertz-Shargel

Construction of Amazon’s Mid-Atlantic Region data center in Loudon County, Virginia, progresses on Feb. 10, 2024.

Gerville via Getty Images

Ben Hertz-Shargel is global head of grid edge at Wood Mackenzie.

The obligation to satisfy an unprecedented number of large load requests, while at the same supporting corporate and state clean energy goals, has presented an enormous ratemaking challenge to utilities. They have responded by developing two types of tariffs to deal with large loads: Clean transition tariffs, which allow large load customers to contract directly with renewable developers, and large load tariffs, designed to protect utility shareholders and other customers from the cost and stranded asset risk of large load-caused infrastructure.

We recently completed an analysis of 20 large load tariffs at varying stages of maturity — from recent proposals to updates of longstanding large commercial and industrial tariffs — and have concluded that these tariffs cannot protect both shareholders and other customers.

One of the primary mechanisms that large load tariffs use to ensure utility cost recovery is to set long minimum contract terms for customers, with penalties for early exit. But the minimum terms are nearly always 12 years or less, with customers able to exit as soon as five years in nearly all cases. These periods are far shorter than the greater than 20-year recovery time for a new power plant. In the vast majority of cases, exit penalties amount to 3 to 5 years of minimum monthly charges, which is a strong disincentive but doesn’t change the equation.

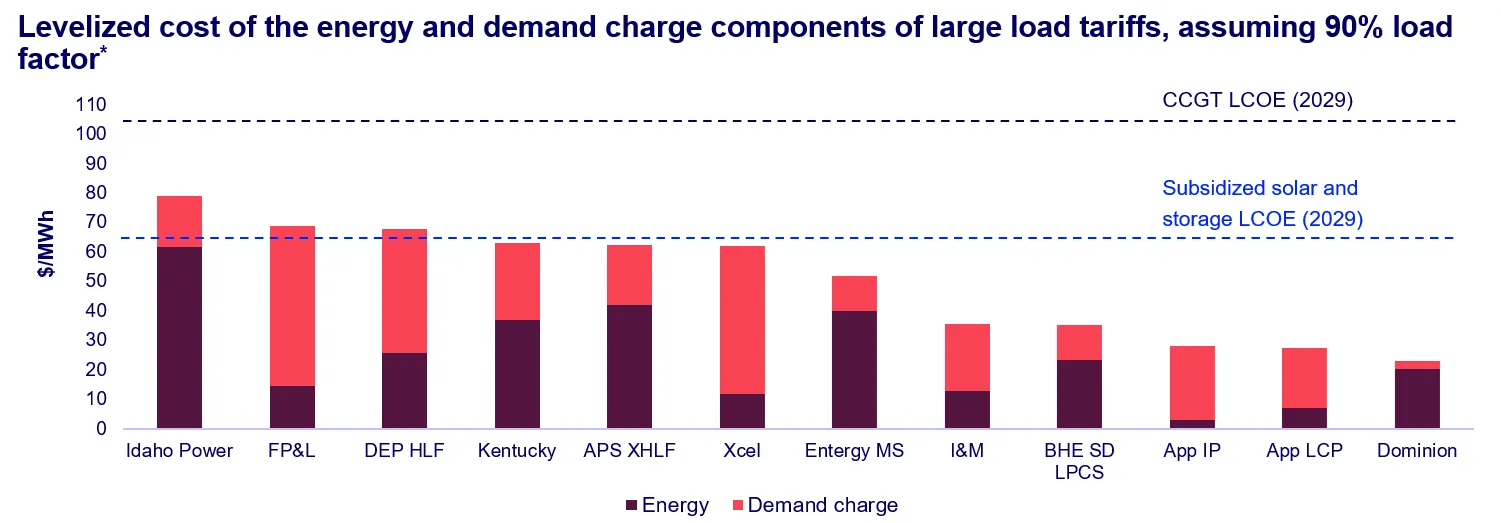

Another key feature of the tariffs is an increased $/kW-month demand charge rate, often to more than twice that for the utility’s smaller commercial customers. But levelizing this cost on a $/MWh basis (assuming a 90% load factor) and adding to the tariff’s energy rate yields a value which is, in all cases, far below the levelized cost of a new combined cycle gas turbine. That means utilities will take in too little revenue to finance or offtake from a new gas plant, and only for over a fraction of that asset’s life.

Optional Caption

Permission granted by Wood Mackenzie

Faced with a revenue shortfall for the new generation assets they will need to build or offtake from, utilities will be forced to make a choice: Absorb the shortfall, burdening shareholders, or rate base them, burdening other customers.

There are limited options to mitigate this situation within the large load tariff framework. One option is to prioritize solar and storage hybrid projects, which have a lower levelized cost than gas and which also forward customer, utility and state clean energy goals. Another is to negotiate stricter terms in electricity supply agreements (ESAs) than are enshrined in the tariff, such as longer contract durations and higher rates. Utilities could also require customers to pay upfront for a portion of new generation assets through their contribution in aid of construction, reducing dependence on future monthly charges.

These options are still likely to leave substantial stranded asset risk on the table, however, and be deeply unpopular with large load developers. Relying on terms in ESAs to be stricter than those in large load tariffs also renders these tariffs toothless, and largely defeats their purpose. It also entails less transparency and would not guarantee equal treatment of large load customers, as ESA negotiations are usually confidential.

Another option is to enable large load customers to mitigate each other’s risk: Allow one customer to assign unused capacity to another on a monthly basis (as AES Ohio has proposed) or on a permanent basis, following a contract exit (as Indiana Michigan Power has proposed). The two customers would be responsible for any incremental cost to the utility to serve the new configuration. This would improve infrastructure utilization and mitigate the impact of customer exits. But it still wouldn’t let shareholders and ratepayers off the hook in the cases where a replacement customer cannot be found.

The only way that utilities can fully shield these stakeholders is to allow third party independent power producers to build and take the long-term contract risk for new generation assets. And that brings us back to clean transition tariffs. NV Energy’s proposal has received the most attention, but many other utilities have similar tariffs established or in development, including Arizona Public Service, Idaho Power, Duke Energy and Portland General Electric. These tariffs were designed to offer large load developers access to renewable energy projects, but they could be expanded to baseload generation and serve the dual purpose of removing at-risk generation from the utility’s books.

The buy-in from major utilities shows crucially that vertically-integrated utilities don’t need to fear this model as a form of deregulation: giving up generation. The unprecedented risk they face from a small set of individual customers demands that some if not all of that risk be borne by third-party capital, particularly if outside investors are ready to step in. Utility shareholders should have the opportunity to be that capital provider, but not be forced to from the utility’s obligation to serve load, and only through an unregulated business, to forego the rate base lifeline.

Clean transition tariffs plug the hole in large load tariffs. They should be used not just as a pathway for clean energy but a mechanism to more deliberately allocate risk.

<!– –>