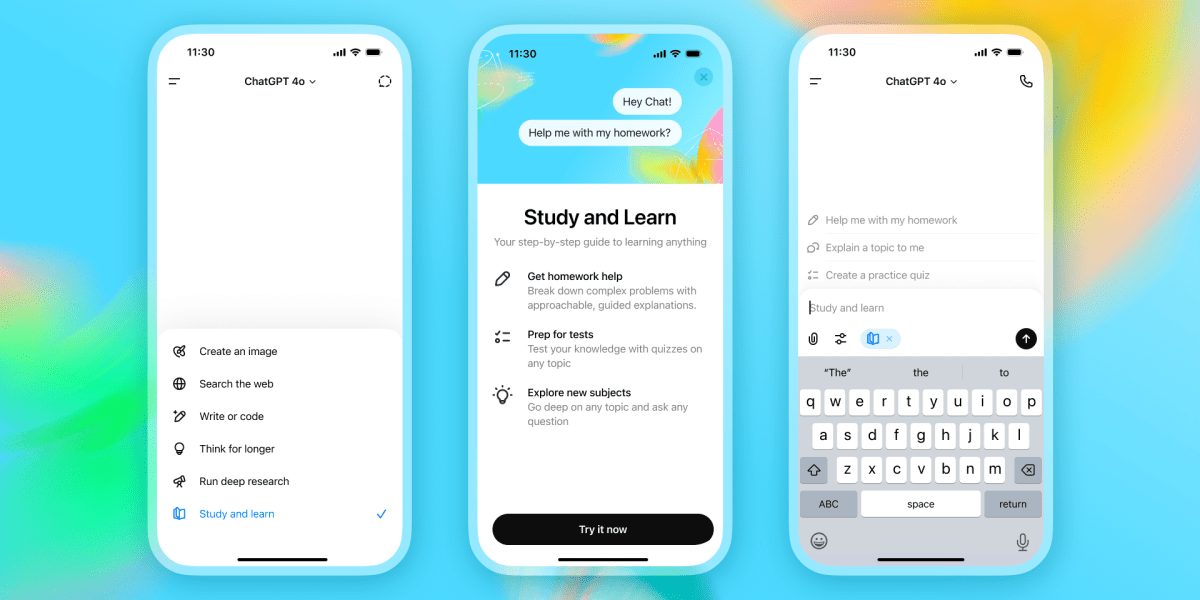

OpenAI is launching Study Mode, a version of ChatGPT for college students that it promises will act less like a lookup tool and more like a friendly, always-available tutor. It’s part of a wider push by the company to get AI more embedded into classrooms when the new academic year starts in September.

A demonstration for reporters from OpenAI showed what happens when a student asks Study Mode about an academic subject like game theory. The chatbot begins by asking what the student wants to know and then attempts to build an exchange, where the pair work methodically toward the answer together. OpenAI says the tool was built after consulting with pedagogy experts from over 40 institutions.

A handful of college students who were part of OpenAI’s testing cohort—hailing from Princeton, Wharton, and the University of Minnesota—shared positive reviews of Study Mode, saying it did a good job of checking their understanding and adapting to their pace.

The learning approaches that OpenAI has programmed into Study Mode, which are based partially on Socratic methods, appear sound, says Christopher Harris, an educator in New York who has created a curriculum aimed at AI literacy. They might grant educators more confidence about allowing, or even encouraging, their students to use AI. “Professors will see this as working with them in support of learning as opposed to just being a way for students to cheat on assignments,” he says.

But there’s a more ambitious vision behind Study Mode. As demonstrated in OpenAI’s recent partnership with leading teachers’ unions, the company is currently trying to rebrand chatbots as tools for personalized learning rather than cheating. Part of this promise is that AI will act like the expensive human tutors that currently only the most well-off students’ families can typically afford.

“We can begin to close the gap between those with access to learning resources and high-quality education and those who have been historically left behind,” says OpenAI’s head of education. Leah Belsky.

But painting Study Mode as an education equalizer obfuscates one glaring problem. Underneath the hood, it is not a tool trained exclusively on academic textbooks and other approved materials—it’s more like the same old ChatGPT, tuned with a new conversation filter that simply governs how it responds to students, encouraging fewer answers and more explanations.

This AI tutor, therefore, more resembles what you’d get if you hired a human tutor who has read every required textbook, but also every flawed explanation of the subject ever posted to Reddit, Tumblr, and the farthest reaches of the web. And because of the way AI works, you can’t expect it to distinguish right information from wrong.

Professors encouraging their students to use it run the risk of it teaching them to approach problems in the wrong way—or worse, being taught material that is fabricated or entirely false.

Given this limitation, I asked OpenAI if Study Mode is limited to particular subjects. The company said no—students will be able to use it to discuss anything they’d normally talk to ChatGPT about.

It’s true that access to human tutors—which for certain subjects can cost upward of $200 an hour—is typically for the elite few. The notion that AI models can spread the benefits of tutoring to the masses holds an allure. Indeed, it is backed up by at least some early research that shows AI models can adapt to individual learning styles and backgrounds.

But this improvement comes with a hidden cost. Tools like Study Mode, at least for now, take a shortcut by using large language models’ humanlike conversational style without fixing their inherent flaws.

OpenAI also acknowledges that this tool won’t prevent a student who’s frustrated and wants an answer from simply going back to normal ChatGPT. “If someone wants to subvert learning, and sort of get answers and take the easier route, that is possible,” Belsky says.

However, one thing going for Study Mode, the students say, is that it’s simply more fun to study with a chatbot that’s always encouraging you along than to stare at a textbook on Bayesian theorem for the hundredth time. “It’s like the reward signal of like, oh, wait, I can learn this small thing,” says Maggie Wang, a student from Princeton who tested it. The tool is free for now, but Praja Tickoo, a student from Wharton, says it wouldn’t have to be for him to use it. “I think it’s absolutely something I would be willing to pay for,” he says.