At first glance, it seems as if life teems around Carmen Suárez Vázquez’s little teal-painted house in the municipality of Guayama, on Puerto Rico’s southeastern coast.

The edge of the Aguirre State Forest, home to manatees, reptiles, as many as 184 species of birds, and at least three types of mangrove trees, is just a few feet south of the property line. A feral pig roams the neighborhood, trailed by her bumbling piglets. Bougainvillea blossoms ring brightly painted houses soaked in Caribbean sun.

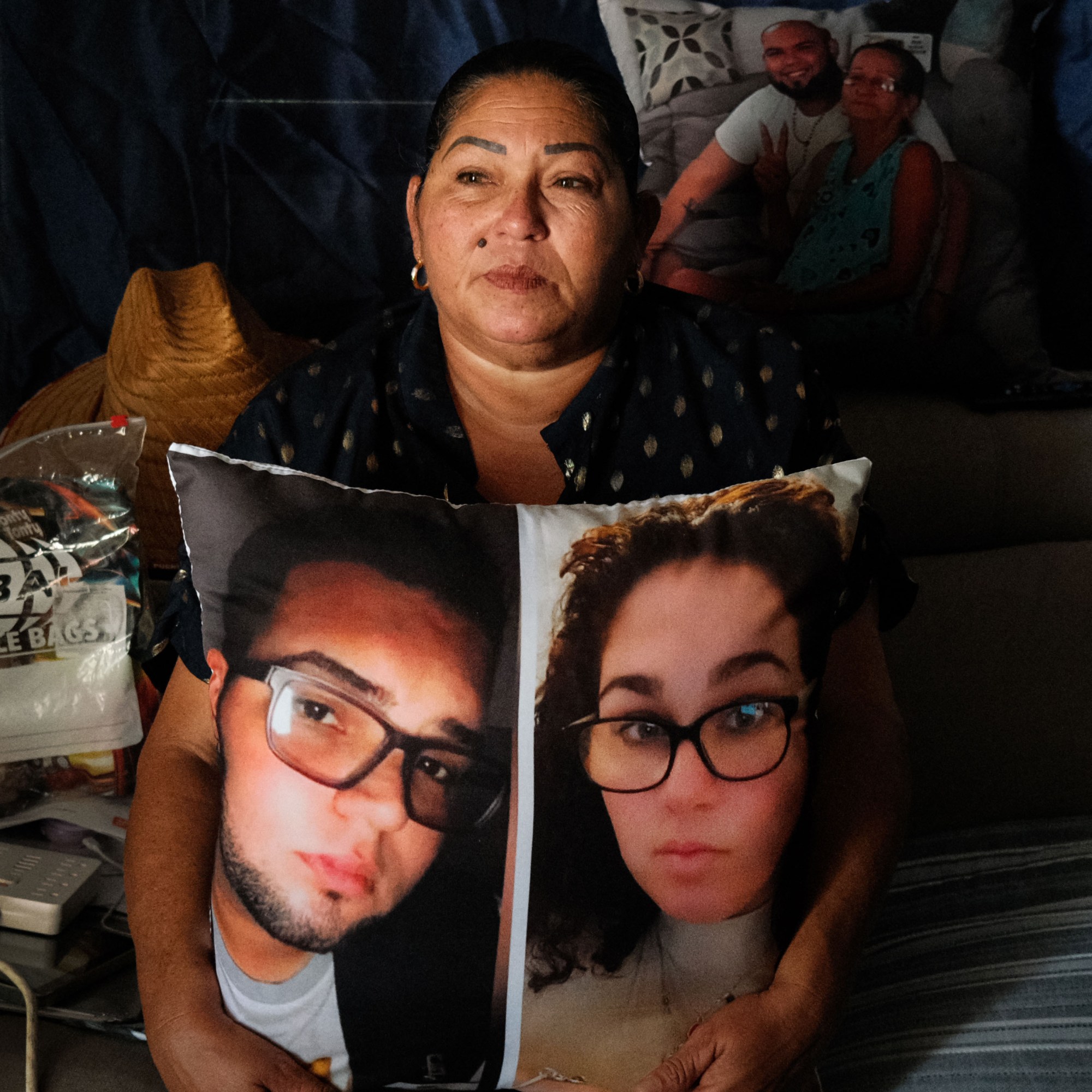

Yet fine particles of black dust coat the windowpanes and the leaves of the blooming vines. Because of this, Suárez Vázquez feels she is stalked by death. The dust is in the air, so she seals her windows with plastic to reduce the time she spends wheezing—a sound that has grown as natural in this place as the whistling croak of Puerto Rico’s ubiquitous coquí frog. It’s in the taps, so a watercooler and extra bottles take up prime real estate in her kitchen. She doesn’t know exactly how the coal pollution got there, but she is certain it ended up in her youngest son, Edgardo, who died of a rare form of cancer.

And she believes she knows where it came from. Just a few minutes’ drive down the road is Puerto Rico’s only coal-fired power station, flanked by a mountain of toxic ash.

The plant, owned by the utility giant AES, has long plagued this part of Puerto Rico with air and water pollution. During Hurricane Maria in 2017, powerful winds and rain swept the unsecured pile—towering more than 12 stories high—out into the ocean and the surrounding area. Though the company had moved millions of tons of ash around Puerto Rico to be used in construction and landfill, much of it had stayed in Guayama, according to a 2018 investigation by the Centro de Periodismo Investigativo, a nonprofit investigative newsroom. Last October, AES settled with the US Environmental Protection Agency over alleged violations of groundwater rules, including failure to properly monitor wells and notify the public about significant pollution levels.

Governor Jenniffer González-Colón has signed a new law rolling back the island’s clean-energy statute, completely eliminating its initial goal of 40% renewables by 2025.

Between 1990 and 2000—before the coal plant opened—Guayama had on average just over 103 cancer cases per year. In 2003, the year after the plant opened, the number of cancer cases in the municipality surged by 50%, to 167. In 2022, the most recent year with available data in Puerto Rico’s central cancer registry, cases hit a new high of 209—a more than 88% increase from the year AES started burning coal. A study by University of Puerto Rico researchers found cancer, heart disease, and respiratory illnesses on the rise in the area. They suggested that proximity to the coal plant may be to blame, describing the “operation, emissions, and handling of coal ash from the company” as “a case of environmental injustice.”

Seemingly everyone Suárez Vázquez knows has some kind of health problem. Nearly every house on her street has someone who’s sick, she told me. Her best friend, who grew up down the block, died of cancer a year ago, aged 55. Her mother has survived 15 heart attacks. Her own lungs are so damaged she requires a breathing machine to sleep at night, and she was forced to quit her job at a nearby pharmaceutical factory because she could no longer make it up and down the stairs without gasping for air.

When we met in her living room one sunny March afternoon, she had just returned from two weeks in the hospital, where doctors were treating her for lung inflammation.

“In one community, we have so many cases of cancer, respiratory problems, and heart disease,” she said, her voice cracking as tears filled her eyes and she clutched a pillow on which a photo of Edgardo’s face was printed. “It’s disgraceful.”

Neighbors have helped her install solar panels and batteries on the roof of her home, helping to offset the cost of running her air conditioner, purifier, and breathing machine. They also allow the devices to operate even when the grid goes down—as it still does multiple times a week, nearly eight years after Hurricane Maria laid waste to Puerto Rico’s electrical infrastructure.

Suárez Vázquez had hoped that relief would be on the way by now. That the billions of dollars Congress designated for fixing the island’s infrastructure would have made solar panels ubiquitous. That AES’s coal plant, which for nearly a quarter century has supplied up to 20% of the old, faulty electrical grid’s power, would be near its end—its closure had been set for late 2027. That the Caribbean’s first virtual power plant—a decentralized network of solar panels and batteries that could be remotely tapped into and used to balance the grid like a centralized fuel-burning station—would be well on its way to establishing a new model for the troubled island.

Puerto Rico once seemed to be on that path. In 2019, two years after Hurricane Maria sent the island into the second-longest blackout in world history, the Puerto Rican government set out to make its energy system cheaper, more resilient, and less dependent on imported fossil fuels, passing a law that set a target of 100% renewable energy by 2050. Under the Biden administration, a gas company took charge of Puerto Rico’s power plants and started importing liquefied natural gas (LNG), while the federal government funded major new solar farms and programs to install panels and batteries on rooftops across the island.

Now, with Donald Trump back in the White House and his close ally Jenniffer González-Colón serving as Puerto Rico’s governor, America’s largest unincorporated territory is on track for a fossil-fuel resurgence. The island quietly approved a new gas power plant in 2024, and earlier this year it laid out plans for a second one. Arguing that it was the only way to avoid massive blackouts, the governor signed legislation to keep Puerto Rico’s lone coal plant open for at least another seven years and potentially more. The new law also rolls back the island’s clean-energy statute, completely eliminating its initial goals of 40% renewables by 2025 and 60% by 2040, though it preserves the goal of reaching 100% by 2050. At the start of April, González-Colón issued an executive order fast-tracking permits for new fossil-fuel plants.

In May the new US energy secretary, Chris Wright, redirected $365 million in federal funds the Biden administration had committed to solar panels and batteries to instead pay for “practical fixes and emergency activities” to improve the grid.

It’s all part of a desperate effort to shore up Puerto Rico’s grid before what’s forecast to be a hotter-than-average summer—and highlights the thorny bramble of bureaucracy and business deals that prevents the territory’s elected government from making progress on the most basic demand from voters to restore some semblance of modern American living standards.

Puerto Ricans already pay higher electricity prices than most other American citizens, and Luma Energy, the private company put in charge of selling and distributing power from the territory’s state-owned generating stations four years ago, keeps raising rates despite ongoing outages. In April González-Colón moved to crack down on Luma, whose contract she pledged to cancel on the campaign trail, though it remains unclear how she will find a suitable replacement.

At the same time, she’s trying to enforce a separate contract with New Fortress Energy, the New York–based natural-gas company that gained control of Puerto Rico’s state-owned power plants in a hotly criticized privatization deal in 2023—all while the company is pushing to build more gas-fired generating stations to increase the island’s demand for liquefied natural gas. Just weeks before the coal plant won its extension, New Fortress secured a deal to sell even more LNG to Puerto Rico—despite the company’s failure to win federal permits for a controversial import terminal in San Juan Bay, already in operation, that critics fear puts the most densely populated part of the island at major risk, with no real plan for what to do if something goes wrong.

Those contracts infamously offered Luma and New Fortress plenty of carrots in the form of decades-long deals and access to billions of dollars in federal reconstruction money, but few sticks the Puerto Rican government could wield against them when ratepayers’ lights went out and prices went up. In a sign of how dim the prospects for improvement look, New Fortress even opted in March to forgo nearly $1 billion in performance bonuses over the next decade in favor of getting $110 million in cash up front. Spending any money to fix the problems Puerto Rico faces, meanwhile, requires approval from an unelected fiscal control board that Congress put in charge of the territory’s finances during a government debt crisis nearly a decade ago, further reducing voters’ ability to steer their own fate.

AES declined an interview with MIT Technology Review and did not respond to a detailed list of emailed questions. Neither New Fortress nor a spokesperson for González-Colón responded to repeated requests for comment.

“I was born on Puerto Rico’s Emancipation Day, but I’m not liberated because that coal plant is still operating,” says Alberto Colón, 75, a retired public school administrator who lives across the street from Suárez Vázquez, referring to the holiday that celebrates the abolition of slavery in what was then a Spanish colony. “I have sinus problems, and I’m lucky. My wife has many, many health problems. It’s gotten really bad in the last few years. Even with screens in the windows, the dust gets into the house.”

El problema es la colonia

What’s happening today in Puerto Rico began long before Hurricane Maria made landfall over the territory, mangling its aging power lines like a metal Slinky in a blender.

The question for anyone who visits this place and tries to understand why things are the way they are is: How did it get this bad?

The complicated answer is a story about colonialism, corruption, and the challenges of rebuilding an island that was smothered by debt—a direct consequence of federal policy changes in the 1990s. Although they are citizens, Puerto Ricans don’t have votes that count in US presidential elections. They don’t typically pay US federal income taxes, but they also don’t benefit fully from federal programs, receiving capped block grants that frequently run out. Today the island has even less control over its fate than in years past and is entirely beholden to a government—the US federal government—that its 3.2 million citizens had no part in choosing.

What’s happening today in Puerto Rico began long before Hurricane Maria made landfall over the territory, mangling its aging power lines like a metal Slinky in a blender.

A phrase that’s ubiquitous in graffiti on transmission poles and concrete walls in the towns around Guayama and in the artsy parts of San Juan places the blame deep in history: El problema es la colonia—the problem is the colony.

By some measures, Puerto Rico is the world’s oldest colony, officially established under the Spanish crown in 1508. The US seized the island as a trophy in 1898 following its victory in the Spanish-American War. In the grips of an expansionist quest to place itself on par with European empires, Washington pried Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines away from Madrid, granting each territory the same status then afforded to the newly annexed formerly independent kingdom of Hawaii. Acolytes of President William McKinley saw themselves as accepting what the Indian-born British poet Rudyard Kipling called “the white man’s burden”—the duty to civilize his subjects.

Although direct military rule lasted just two years, Puerto Ricans had virtually no say over the civil government that came to power in 1900, in which the White House appointed the governor. That explicitly colonial arrangement ended only in 1948 with the first island-wide elections for governor. Even then, the US instituted a gag law just months before the election that would remain in effect for nearly a decade, making agitation for independence illegal. Still, the following decades were a period of relative prosperity for Puerto Rico. Money from President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal had modernized the island’s infrastructure, and rural farmers flocked to bustling cities like Ponce and San Juan for jobs in the burgeoning manufacturing sector. The pharmaceutical industry in particular became a major employer. By the start of the 21st century, Pfizer’s plant in the Puerto Rican town of Barceloneta was the largest Viagra manufacturer in the world.

But in 1996, Republicans in Congress struck a deal with President Bill Clinton to phase out federal tax breaks that had helped draw those manufacturers to Puerto Rico. As factories closed, the jobs that had built up the island’s middle class disappeared. To compensate, the government hired more workers as teachers and police officers, borrowing money on the bond market to pay their salaries and make up for the drop in local tax revenue. Puerto Rico’s territorial status meant it could not legally declare bankruptcy, and lenders assumed the island enjoyed the full backing of the US Treasury. Before long, it was known on Wall Street as the “belle of the bond markets.” By the mid-2010s, however, the bond debt had grown to $74 billion, and a $49 billion chasm had opened between the amount the government needed to pay public pensions and the money it had available. It began shedding more and more of its payroll.

The Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA), the government-owned utility, had racked up $9 billion in debt. Unlike US states, which can buy electricity from neighboring grids and benefit from interstate gas pipelines, Puerto Rico needed to import fuel to run its power plants. The majority of that power came from burning oil, since petroleum was easier to store for long periods of time. But oil, and diesel in particular, was expensive and pushed the utility further and further into the red.

By 2016, Puerto Rico could no longer afford to pay its bills. Since the law that gave the US jurisdiction over nonstate territories made Puerto Rico a “possession” of Congress, it fell on the federal legislature—in which the island’s elected delegate had no vote—to decide what to do. Congress passed the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act—shortened to PROMESA, or “promise” in Spanish. It established a fiscal control board appointed by the White House, with veto power over all spending by the island’s elected government. The board had authority over how the money the territorial government collected in taxes and utility bills could be used. It was a significant shift in the island’s autonomy.

“The United States cannot continue its state of denial by failing to accept that its relationship with its citizens who reside in Puerto Rico is an egregious violation of their civil rights,” Juan R. Torruella, the late federal appeals court judge, wrote in a landmark paper in the Harvard Law Review in 2018, excoriating the legislation as yet another “colonial experiment.” “The democratic deficits inherent in this relationship cast doubt on its legitimacy, and require that it be frontally attacked and corrected ‘with all deliberate speed.’”

Hurricane Maria struck a little over a year after PROMESA passed, and according to official figures, killed dozens. That proved to be just the start, however. As months ground on without any electricity and more people were forced to go without medicine or clean water, the death toll rose to the thousands. It would be 11 months before the grid would be fully restored, and even then, outages and appliance-destroying electrical surges were distressingly common.

The spotty service wasn’t the only defining characteristic of the new era after Puerto Rico’s great blackout. The fiscal control board—which critics pejoratively referred to as “la junta,” using a term typically reserved for Latin America’s most notorious military dictatorships—saw privatization as the best path to solvency for the troubled state utility.

In 2020, the board approved a deal for Luma Energy—a joint venture between Quanta Services, a Texas-based energy infrastructure company, and its Canadian rival ATCO—to take over the distribution and sale of electricity in Puerto Rico. The contract was awarded through a process that clean-energy and anticorruption advocates said lacked transparency and delivered an agreement with few penalties for poor service. It was almost immediately mired in controversy.

A deadly diagnosis

Until that point, life was looking up for Suárez Vázquez. Her family had emerged from the aftermath of Maria without any loss of life. In 2019, her children were out of the house, and her youngest son, Edgardo, was studying at an aviation school in Ceiba, roughly two hours northeast of Guayama. He excelled. During regular health checks at the school, Edgardo was deemed fit. Gift bags started showing up at the house from American Airlines and JetBlue.

“They were courting him,” Suárez Vázquez says. “He was going to graduate with a great job.”

That summer of 2019, however, Edgardo began complaining of abdominal pain. He ignored it for a few months but promised his mother he would go to the doctor to get it checked out. On September 23, she got a call from her godson, a radiologist at the hospital. Not wanting to burden his anxious mother, Edgardo had gone to the hospital alone at 3 a.m., and tests had revealed three tumors entwined in his intestines.

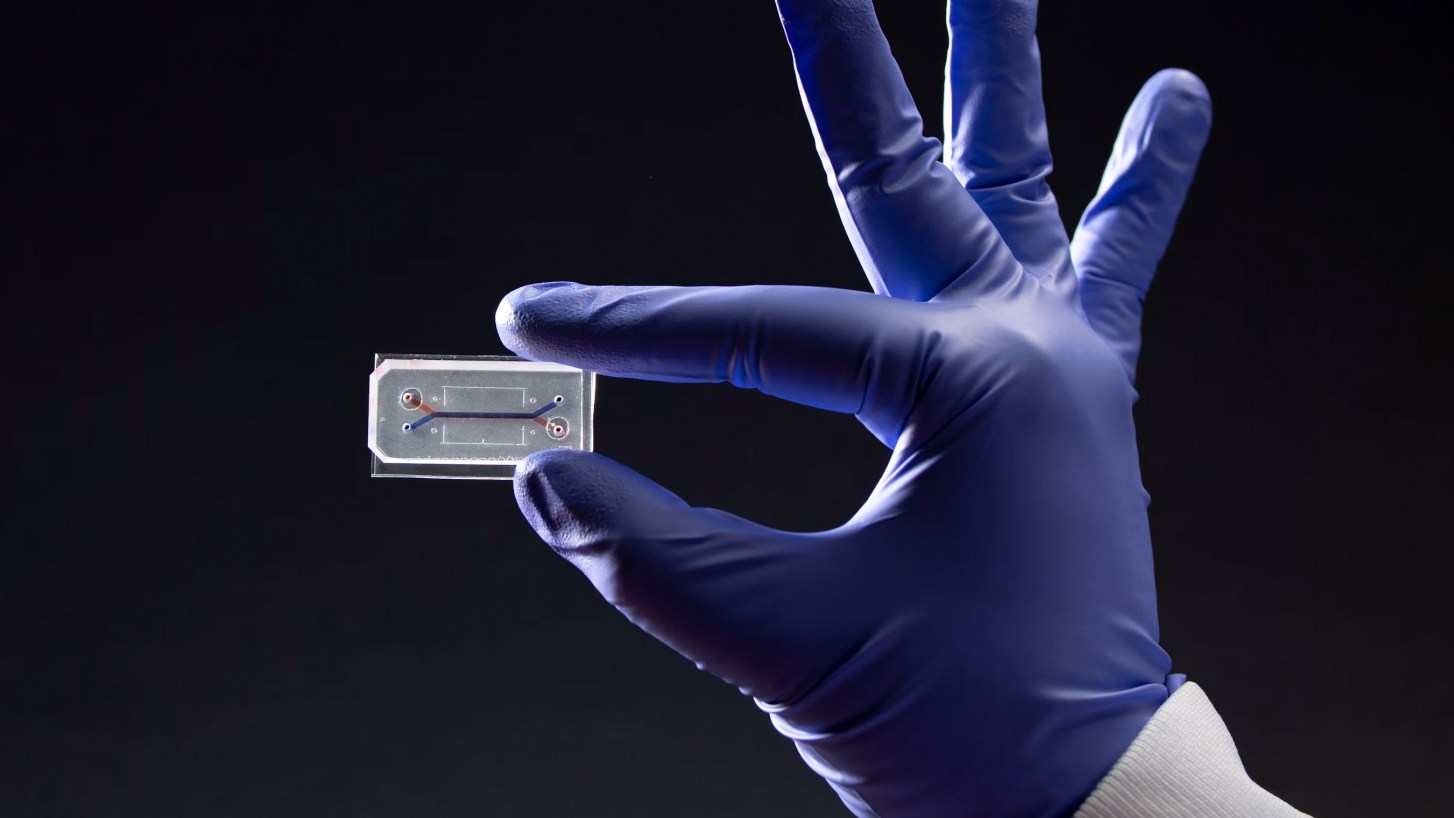

So began a two-year battle with a form of cancer so rare that doctors said Edgardo’s case was one of only a few hundred worldwide. He gave up on flight school and took a job at the pharmaceutical factory with his parents. Coworkers raised money to help the family afford flights and stays to see specialists in other parts of Puerto Rico and then in Florida. Edgardo suspected the cause was something in the water. Doctors gave him inconclusive answers; they just wanted to study him to understand the unusual tumors. He got water-testing kits and discovered that the taps in their home were laden with high amounts of heavy metals typically found in coal ash.

Ewing’s sarcoma tumors occur at a rate of about one in one million cancer diagnoses in the US each year. What Edgardo had—extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma, in which tumors form in soft tissue rather than bone—is even rarer.

As a result, there’s scant research on what causes that kind of cancer. While the National Institutes of Health have found “no well-established association between Ewing sarcoma and environmental risk factors,” researchers cautioned in a 2024 paper that findings have been limited to “small, retrospective, case-control studies.”

Dependable sun

The push to give control over the territory’s power system to private companies with fossil-fuel interests ignored the reality that for many Puerto Ricans, rooftop solar panels and batteries were among the most dependable options for generating power after the hurricane. Solar power was relatively affordable, especially as Luma jacked up what were already some of the highest electricity rates in the US. It also didn’t lead to sudden surges that fried refrigerators and microwaves. Its output was as predictable as Caribbean sunshine.

But rooftop panels could generate only so much electricity for the island’s residents. Last year, when the Biden administration’s Department of Energy conducted its PR100 study into how Puerto Rico could meet its legally mandated goals of 100% renewable power by the middle of the century, the research showed that the bulk of the work would need to be done by big, utility-scale solar farms.

With its flat lands once used to grow sugarcane, the southeastern part of Puerto Rico proved perfect for devoting acres to solar production. Several enormous solar farms with enough panels to generate hundreds of megawatts of electricity were planned for the area, including one owned by AES. But early efforts to get the projects off the ground stumbled once the fiscal oversight board got involved. The solar farms that Puerto Rico’s energy regulators approved ultimately faced rejection by federal overseers who complained that the panels in areas near Guayama could be built even more cheaply.

In a September 2023 letter to PREPA vetoing the projects, the oversight board’s lawyer chastised the Puerto Rico Energy Bureau, a government regulatory body whose five commissioners are appointed by the governor, for allowing the solar developers to update contracts to account for surging costs from inflation that year. It was said to have created “a precedent that bids will be renegotiated, distorting market pricing and creating litigation risk.” In another letter to PREPA, in January 2024, the board agreed to allow projects generating up to 150 megawatts of power to move forward, acknowledging “the importance of developing renewable energy projects.”

“There’s no trust. That creates risk. Risk means more money. Things get more expensive. It’s disappointing, but that’s why we weren’t able to build large things.”

But that was hardly enough power to provide what the island needed, and critics said the agreement was guilty of the very thing the board accused Puerto Rican regulators of doing: discrediting the permitting process in the eyes of investors.

The Puerto Rico Energy Bureau “negotiated down to the bone to very inexpensive prices” on a handful of projects, says Javier Rúa-Jovet, the chief policy officer at the Solar & Energy Storage Association of Puerto Rico. “Then the fiscal board—in my opinion arbitrarily—canceled 450 megawatts of projects, saying they were expensive. That action by the fiscal board was a major factor in predetermining the failure of all future large-scale procurements,” he says.

When the independence of the Puerto Rican regulator responsible for issuing and judging the requests for proposals is overruled, project developers no longer believe that anything coming from the government’s local experts will be final. “There’s no trust,” says Rúa-Jovet. “That creates risk. Risk means more money. Things get more expensive. It’s disappointing, but that’s why we weren’t able to build large things.”

That isn’t to say the board alone bears all responsibility. An investigation released in January by the Energy Bureau blamed PREPA and Luma for causing “deep structural inefficiencies” that “ultimately delayed progress” toward Puerto Rico’s renewables goals.

The finding only further reinforced the idea that the most trustworthy path to steady power would be one Puerto Ricans built themselves. At the residential scale, Rúa-Jovet says, solar and batteries continue to be popular. Nearly 160,000 households—roughly 13% of the population—have solar panels, and 135,000 of them also have batteries. Of those, just 8,500 households are enrolled in the pilot virtual power plant, a collection of small-scale energy resources that have aggregated together and coordinated with grid operations. During blackouts, he says, Luma can tap into the network of panels and batteries to back up the grid. The total generation capacity on a sunny day is nearly 600 megawatts—eclipsing the 500 megawatts that the coal plant generates. But the project is just at the pilot stage.

The share of renewables on Puerto Rico’s power grid hit 7% last year, up one percentage point from 2023. That increase was driven primarily by rooftop solar. Despite the growth and dependability of solar, in December Puerto Rican regulators approved New Fortress’s request to build an even bigger gas power station in San Juan, which is currently scheduled to come online in 2028.

“There’s been a strong grassroots push for a decentralized grid,” says Cathy Kunkel, a consultant who researches Puerto Rico for the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis and lived in San Juan until recently. She’d be more interested, she adds, if the proposals focused on “smaller-scale natural-gas plants” that could be used to back up renewables, but “what they’re talking about doing instead are these giant gas plants in the San Juan metro area.” She says, “That’s just not going to provide the kind of household level of resilience that people are demanding.”

What’s more, New Fortress has taken a somewhat unusual approach to storing its natural gas. The company has built a makeshift import terminal next to a power plant in a corner of San Juan Bay by semipermanently mooring an LNG tanker, a vessel specifically designed for transport. Since Puerto Rico has no connections to an interstate pipeline network, New Fortress argued that the project didn’t require federal permits under the law that governs most natural-gas facilities in the US. As a result, the import terminal did not get federal approval for a safety plan in case of an accident like the ones that recently rocked Texas and Louisiana.

Skipping the permitting process also meant skirting public hearings, spurring outrage from Catholic clergy such as Lissette Avilés-Ríos, an activist nun who lives in the neighborhood next to the import terminal and who led protests to halt gas shipments. “Imagine what a hurricane like Maria could do to a natural-gas station like that,” she told me last summer, standing on the shoreline in front of her parish and peering out on San Juan Bay. “The pollution impact alone would be horrible.”

The shipments ultimately did stop for a few months—but not because of any regulatory enforcement. In fact, it was in violation of its contract that New Fortress abruptly cut off shipments when the price of natural gas skyrocketed globally in late 2021. When other buyers overseas said they’d pay higher prices for LNG than the contract in Puerto Rico guaranteed, New Fortress announced with little notice that it would cease deliveries for six months while upgrading its terminal.

“The government justifies extending coal plants because they say it’s the cheapest form of energy.”

Aldwin José Colón, 51, who lives across the street from Suárez Vázquez

The missed shipments exemplified the challenges in enforcing Puerto Rico’s contracts with the private companies that control its energy system and highlighted what Gretchen Sierra-Zorita, former president Joe Biden’s senior advisor on Puerto Rico and the territories, called the “troubling” fact that the same company operating the power plants is selling itself the fuel on which they run—disincentivizing any transition to alternatives.

“Territories want to diversify their energy sources and maximize the use of abundant solar energy,” she told me. “The Trump administration’s emphasis on domestic production of fossil fuels and defunding climate and clean-energy initiatives will not provide the territories with affordable energy options they need to grow their economies, increase their self-sufficiency, and take care of their people.”

Puerto Rico’s other energy prospects are limited. The Energy Department study determined that offshore wind would be too expensive. Nuclear is also unlikely; the small modular reactors that would be the most realistic way to deliver nuclear energy here are still years away from commercialization and would likely cost too much for PREPA to purchase. Moreover, nuclear power would almost certainly face fierce opposition from residents in a disaster-prone place that has already seen how willing the federal government is to tolerate high casualty rates in a catastrophe. That leaves little option, the federal researchers concluded, beyond the type of utility-scale solar projects the fiscal oversight board has made impossible to build.

“Puerto Rico has been unsuccessful in building large-scale solar and large-scale batteries that could have substituted [for] the coal plant’s generation. Without that new, clean generation, you just can’t turn off the coal plant without causing a perennial blackout,” Rúa-Jovet says. “That’s just a physical fact.”

The lowest-cost energy, depending on who’s paying the price

The AES coal plant does produce some of the least expensive large-scale electricity currently available in Puerto Rico, says Cate Long, the founder of Puerto Rico Clearinghouse, a financial research service targeted at the island’s bondholders. “From a bondholder perspective, [it’s] the lowest cost,” she explains. “From the client and user perspective, it’s the lowest cost. It’s always been the cheapest form of energy down there.”

The issue is that the price never factors in the cost to the health of people near the plant.

“The government justifies extending coal plants because they say it’s the cheapest form of energy,” says Aldwin José Colón, 51, who lives across the street from Suárez Vázquez. He says he’s had cancer twice already.

On an island where nearly half the population relies on health-care programs paid for by frequently depleted Medicaid block grants, he says, “the government ends up paying the expense of people’s asthma and heart attacks, and the people just suffer.”

On December 2, 2021, at 9:15 p.m., Edgardo died in the hospital. He was 25 years old. “So many people have died,” Suárez Vázquez told me, choking back tears. “They contaminated the water. The soil. The fish. The coast is black. My son’s insides were black. This never ends.”

Nor do the blackouts. At 12:38 p.m. on April 16, as this story was being edited, all of Puerto Rico’s power plants went down in an island-wide outage triggered by a transmission line failure. As officials warned that the blackout would persist well into the next day, Casa Pueblo, a community group that advocates for rooftop solar, posted an invitation on X to charge phones and go online under its outdoor solar array near its headquarters in a town in the western part of Puerto Rico’s central mountain range.

“Come to the Solar Forest and the Energy Independence Plaza in Adjuntas,” the group beckoned, “where we have electricity and internet.”

Alexander C. Kaufman is a reporter who has covered energy, climate change, pollution, business, and geopolitics for more than a decade.