Picture it: I’m minding my business at a party, parked by the snack table (of course). A friend of a friend wanders up, and we strike up a conversation. It quickly turns to work, and upon learning that I’m a climate technology reporter, my new acquaintance says something like: “Should I be using AI? I’ve heard it’s awful for the environment.”

This actually happens pretty often now. Generally, I tell people not to worry—let a chatbot plan your vacation, suggest recipe ideas, or write you a poem if you want.

That response might surprise some people, but I promise I’m not living under a rock, and I have seen all the concerning projections about how much electricity AI is using. Data centers could consume up to 945 terawatt-hours annually by 2030. (That’s roughly as much as Japan.)

But I feel strongly about not putting the onus on individuals, partly because AI concerns remind me so much of another question: “What should I do to reduce my carbon footprint?”

That one gets under my skin because of the context: BP helped popularize the concept of a carbon footprint in a marketing campaign in the early 2000s. That framing effectively shifts the burden of worrying about the environment from fossil-fuel companies to individuals.

The reality is, no one person can address climate change alone: Our entire society is built around burning fossil fuels. To address climate change, we need political action and public support for researching and scaling up climate technology. We need companies to innovate and take decisive action to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions. Focusing too much on individuals is a distraction from the real solutions on the table.

I see something similar today with AI. People are asking climate reporters at barbecues whether they should feel guilty about using chatbots too frequently when we need to focus on the bigger picture.

Big tech companies are playing into this narrative by providing energy-use estimates for their products at the user level. A couple of recent reports put the electricity used to query a chatbot at about 0.3 watt-hours, the same as powering a microwave for about a second. That’s so small as to be virtually insignificant.

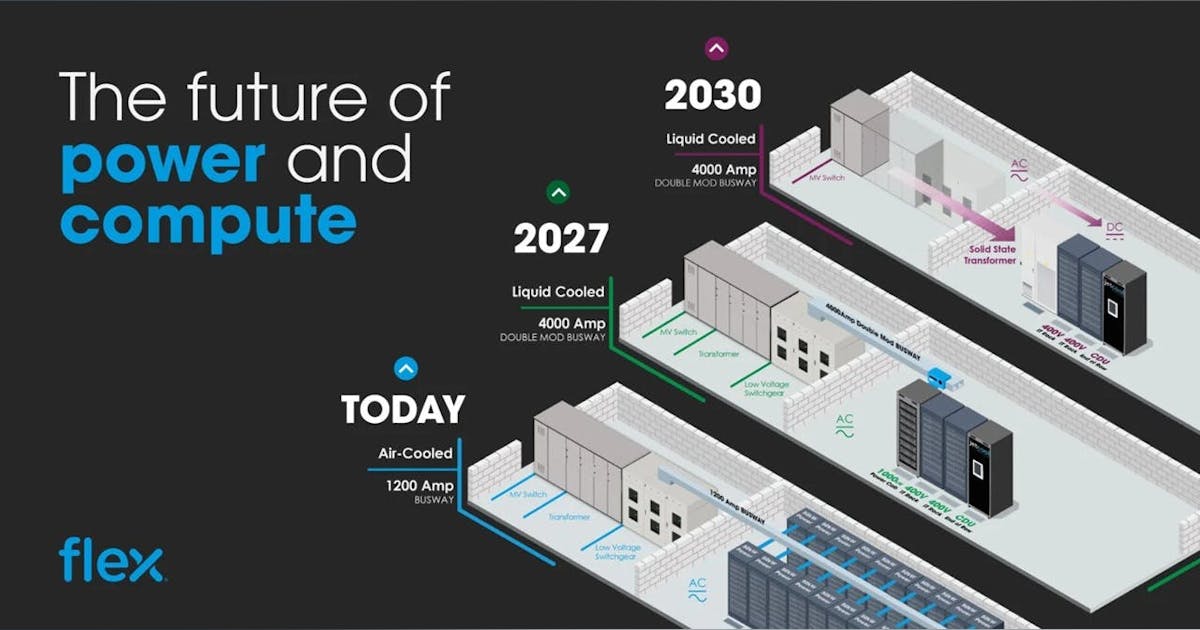

But stopping with the energy use of a single query obscures the full truth, which is that this industry is growing quickly, building energy-hungry infrastructure at a nearly incomprehensible scale to satisfy the AI appetites of society as a whole. Meta is currently building a data center in Louisiana with five gigawatts of computational power—about the same demand as the entire state of Maine at the summer peak. (To learn more, read our Power Hungry series online.)

Increasingly, there’s no getting away from AI, and it’s not as simple as choosing to use or not use the technology. Your favorite search engine likely gives you an AI summary at the top of your search results. Your email provider’s suggested replies? Probably AI. Same for chatting with customer service while you’re shopping online.

Just as with climate change, we need to look at this as a system rather than a series of individual choices.

Massive tech companies using AI in their products should be disclosing their total energy and water use and going into detail about how they complete their calculations. Estimating the burden per query is a start, but we also deserve to see how these impacts add up for billions of users, and how that’s changing over time as companies (hopefully) make their products more efficient. Lawmakers should be mandating these disclosures, and we should be asking for them, too.

That’s not to say there’s absolutely no individual action that you can take. Just as you could meaningfully reduce your individual greenhouse-gas emissions by taking fewer flights and eating less meat, there are some reasonable things that you can do to reduce your AI footprint. Generating videos tends to be especially energy-intensive, as does using reasoning models to engage with long prompts and produce long answers. Asking a chatbot to help plan your day, suggest fun activities to do with your family, or summarize a ridiculously long email has relatively minor impact.

Ultimately, as long as you aren’t relentlessly churning out AI slop, you shouldn’t be too worried about your individual AI footprint. But we should all be keeping our eye on what this industry will mean for our grid, our society, and our planet.

This article is from The Spark, MIT Technology Review’s weekly climate newsletter. To receive it in your inbox every Wednesday, sign up here.