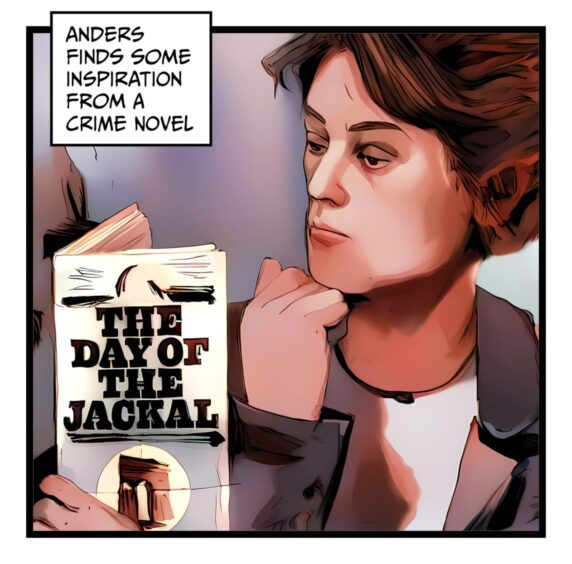

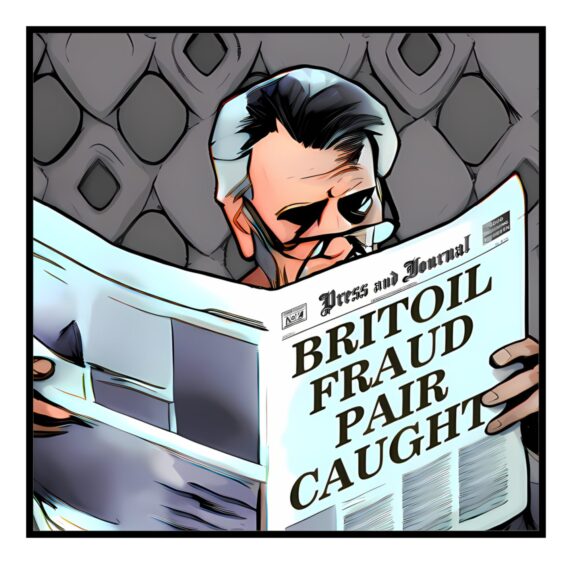

This is an excerpt from a five-part series on a major attempted fraud on Britoil one of the UK’s largest energy firms by Press and Journal investigative journalist Dale Haslam. See the links at the bottom of the page to read the full story.

On a warm summer’s afternoon in 1988, 29-year-old Alison Anders walked along Castle Street in Aberdeen clutching a piece of paper that would change her life forever.

She entered the Bank of Scotland branch, approached the counter and handed over the document, before walking out and heading back to the office.

What seemed at the time to be an innocent clerical errand was to spark a worldwide manhunt – and the astonishing drama surrounding it was just beginning.

Over the course of a year, detectives would crack a series of bizarre clues to track down the mystery of who tried to steal £23 million from a north-east oil firm, how they managed to get away.

The document

The confident, clever 5ft 4in woman, worked as a senior accounts assistant in the finance department.

Ian Adie – Britoil’s financial accountant at the time – describes a call from a bank clerk questioning “extra information on the document Alison had taken into the branch”.

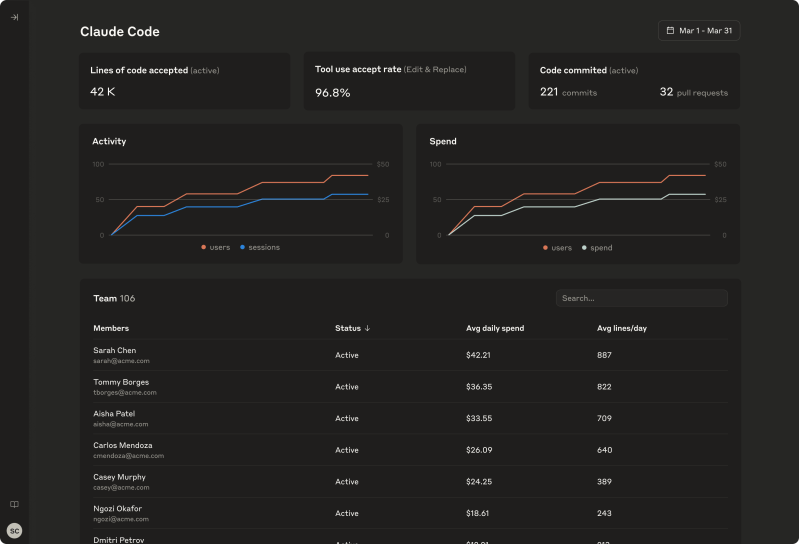

That document was an application to transfer £23,331,996.95 from Britoil to another account.

And the extra information urged the bank to process the payment quickly.

With the internet still years off – the main method of exchanging business documents, besides mail, was fax.

And so Britoil bosses asked the bank to fax through a copy of the document Anders had given to them.

After receiving the fax, Mr Adie felt something was off.

With an abundance of caution, he faxed back a letter to the bank instructing them to “under no circumstances” transfer the money.

“The next time I would see her would be 14 months later in the dock of a court room,” recalled Mr Adie.

Britoil was a massive firm that employed around 1,800 staff at the time.

Anders’ lawyer, Jack Davidson KC, described how his client had been so close to processing the £23m payment order – and pocketing the funds.

“Anders was very close to achieving the unachievable – she really was,” said Mr Davidson.

He added: “When the bank staff in Glasgow raised the questions about the money transfer, all hell was let loose in Britoil offices.”

A crisis meeting at the top

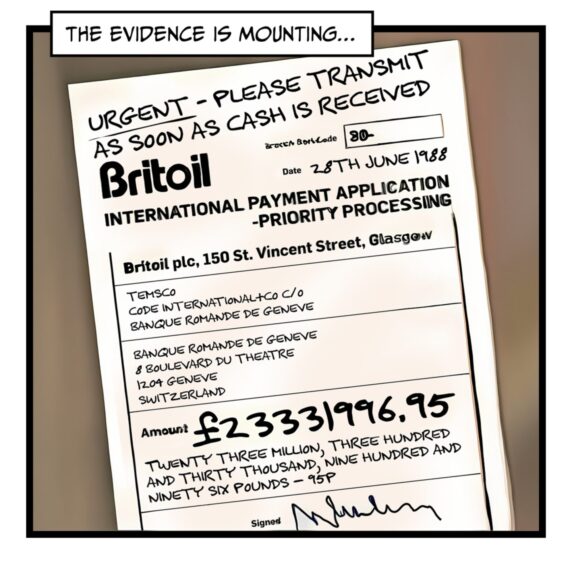

With evidence mounting against Anders, there was only one thing left for the Britoil bosses to do.

“We called in the police,” said Mr Adie.

First on the scene was Detective Constable Hamish Moir, of Aberdeen CID, based at Queen Street.

He said: “I got a message to call from Detective Chief Inspector Harry Milne.

“He said ‘can you come back to the office? There’s an attempted fraud here – £23m’.

“It was the highest-value fraud ever reported in a Scottish court.

The former detective revealed that a seemingly innocuous message that Anders had written on top of the document to convince bank staff it was legitimate was to prove her downfall.

He said: “She had written ‘URGENT! on top of the document.

“Without that, the payment would have gone through.”

He added: “Alison forged both signatures on the document.”

However when they searched her flat she had gone.

It turned out that, a week earlier, Alison Anders had gone into a travel agency in Aberdeen and bought a one-way ticket to Amsterdam for £149.

DC Moir said: “We later learned Anders had fled to Glasgow Airport and panicked before the afternoon flight to Amsterdam and so flew to Paris and on to Abu Dhabi.”

Police were stunned for two reasons.

First, people in the late 1980s didn’t just pack up and go to the Middle East regularly.

It was reserved for people who worked in the oil industry or who were rich enough to afford exotic holidays, not 29-year-old cashiers on low salaries.

Second, police had been keeping tabs on Anders’ passport – and it had not been used.

It took a week for the story to leak out of Britoil and on to the front pages of the Evening Express, though senior staff did their best to keep it in-house.

The next logical step for Grampian Police was to speak with Anders’ parents, James and Elsie, who lived in a leafy part of Kent, in southern England.

And then a new name entered the frame.

Mr Anders, a retired adult education principal, told the officers sitting across from him in his living room that there was another person they might want to quiz.

“She had a bridge partner named Roy Allen – and they’re maybe more than just bridge players,” Mr Anders told the police.

That was the first time detectives had heard the name of Royston Darrell Allen, who was then 35.

He helped start the Granite City Oilers American Football team and was highly respected in the oil industry.

Born in England, Allen had moved to Aberdeen in 1984 to become a partner in Atom UK, which did work for a number of firms, including Britoil.

An office affair

That meant he would often call in to the Britoil offices, passing Anders’ desk.

She found him funny and charismatic, and liked that he shared her love of bridge.

There were feelings of mutual attraction, with one major problem.

Allen was married with two children.

After speaking with Anders’ parents, police were keen to talk to Allen, but he was working offshore, so they awaited his return.

Abu Dhabi the common link

In the meantime, detectives dug into Allen’s business dealings – and found an interesting fact.

DC Moir said: “He was working in Abu Dhabi.

“He is there, we suspect Alison has gone there – that’s the connection.”

Yet Allen was remarkably keen to speak with police.

DC Moir said: “Roy openly admitted that his regular bridge games with Alison were less about the bridge and more about the apres-bridge at Alison’s flat.

“He was worried because his wife didn’t know.

“Roy claimed to know nothing about the crime.

“We had to put that aspect of the inquiry on hold for the time being.”

With no evidence of Roy’s involvement, police could not arrest him.

Another factor was that the Britoil fraud took place a week before one of the worst disasters in the region’s history.

On July 6, 1988, the Piper Alpha oil platform exploded 120 miles off the coast of Aberdeen. The tragedy resulted in the deaths of 167 people.

© Supplied by PA Archive

© Supplied by PA ArchiveIt was a tragedy that stunned the region, overwhelming hospitals and inundated CID.

DC Moir said: “At that time, Piper Alpha had happened.

“So there was a huge amount, maybe 75% of the guys on CID were put on to that investigation.

“There were limited resources to deal with other crimes, so low priorities were put to the side.”

The letter

Eventually police searched Allen’s office to discover a letter taped the the bottom of a drawer.

DC Moir said: “It was a letter from Anders saying ‘I’ve been missing you’. It was quite X-rated in places.

“From that point on, we were certain Roy Allen was involved.

“With this major fraud investigation, things had turned on their head in a couple of days.”

At this point, nine months had passed since the attempt to steal £23m from Britoil and Roy Allen had had multiple opportunities to confess to his involvement.

He appeared at Aberdeen Sheriff Court in connection with attempted fraud and was remanded in custody.

That gave investigators a chance to delve through the treasure trove of new information they had.

Who is Ann Killick?

A name they discovered would finally solve the riddle of how Alison Anders was able to globetrot for almost a full year and evade Interpol.

Ann Killick.

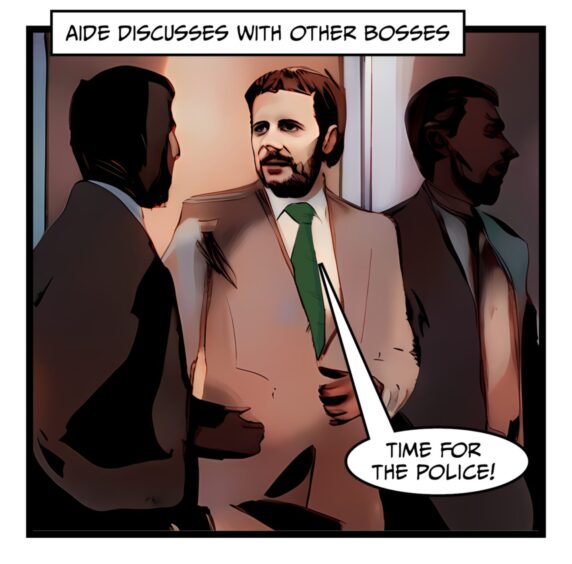

Anders had turned to the plot of Frederick Forsyth’s best-selling novel The Day of the Jackal for inspiration.

A newspaper cutting from 1971 outlined a heartbreaking event involving two young sisters.

Ann Killick was eight and her younger sister Dawn was five when a fatal crash took place on a Tuesday afternoon in August 1971.

She used those details to obtain Ann Killock’s birth and death certificates.

With some further forged documents, she applied for a fast-track passport bearing the name of Ann Killick.

It later became clear that Alison Anders had fled justice in Aberdeen in June 1988 for Abu Dhabi – and then upped sticks once more.

In August 1988, Anders left Abu Dhabi and flew to Singapore and then onwards to Vancouver in Canada.

She then took a Greyhound bus and ended up in Portland, Oregon. She found work as a florist and even found a boyfriend.

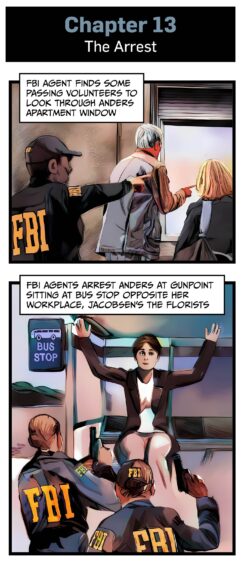

But on May 18 1989 – almost 11 months since the failed fraud and nine months since Anders had arrived in the US she was arrested having been tracked down by the FBI.

Anders was flown back to London and was met by DI Bryan Bryce and DC Ann Allan, of Grampian Police, at Heathrow Airport.

Her arrival back on Scottish soil generated a media frenzy.

Every newspaper around published reports of the £23m oil money plot formed over a game of bridge, with photographers battling for the best place to get a photo of the returning fugitive.

Anders and Allen stood trial at the High Court in Aberdeen on August 28 1989, almost three months after she returned from the US.

And, while there were elements of drama in the courtroom, the trial itself was a damp squib.

Anders and Allen were accused of forming a fraudulent scheme to defraud Britoil of £23,331,996.

The indictment alleged that, between June 28 and 29 1988 – the year before the trial – Anders and Allen acted with others and tried to transfer money from a Britoil account to an account in a Geneva bank, using a forged international payment application.

Anders was also accused of obtaining a false British passport in the name of Ann Glenda Killick.

On day one, Anders wanted to plead guilty to the charges against her.

But there was a problem.

While Anders was willing to admit her guilt, her co-accused Roy Allen was not.

This was despite there being evidence of him forging signatures on the passport and of not telling police he knew where Anders was for months while speaking to her on the phone.

On day three, the prosecution accepted Anders’ guilty plea, leaving Roy Allen as the only person on trial.

Allen’s defence team tried to argue he had been pressured into participating in the fraud by people threatening his children.

DC Moir gave evidence to deny this and the judge, Lord Morton, threw out that defence.

After the trial, DC Moir told us: “After we matched his handwriting to the forged passport, Allen said ‘I want to speak to you in prison – at Craiginches’.

“He admitted limited involvement and said he had been coerced by people and they had threatened his family.

“But there were no specifics. It was just bull***. The game was up for him.”

The trial ended after five days and the jury retired for the weekend.

A quick verdict from the jury

When they came back on the following Monday, they took just 44 minutes to deliberate and return a guilty verdict for Roy Allen.

Lord Morton jailed Anders and Allen for five years, though Anders’ sentence was later reduced to four years on appeal.

Though the Crown had secured two important convictions, the case was far from over.

For, during the trial, one name kept popping up – Hajdin Sejdija.

It was a name that would once again pique the interest of Aberdeen detectives on a quest to crack the case.

Read the full series to find out how a 38-year-old Albanian man with friends in high places had arranged for a Swiss bank account to be opened as part of the scam.

Read the full story on the Press and Journal:

The P&J made several attempts to contact Alison Anders over a period of several months and she did not return our messages.