After Gioia had her first child with her then husband, he installed baby monitors throughout their Massachusetts home—to “watch what we were doing,” she says, while he went to work. She’d turn them off; he’d get angry. By the time their third child turned seven, Gioia and her husband had divorced, but he still found ways to monitor her behavior. One Christmas, he gave their youngest a smartwatch. Gioia showed it to a tech-savvy friend, who found that the watch had a tracking feature turned on. It could be turned off only by the watch’s owner—her ex.

“What am I supposed to tell my daughter?” says Gioia, who is going by a pseudonym in this story out of safety concerns. “She’s so excited but doesn’t realize [it’s] a monitoring device for him to see where we are.” In the end, she decided not to confiscate the watch. Instead, she told her daughter to leave it at home whenever they went out together, saying that this way it wouldn’t get lost.

Gioia says she has informed a family court of this and many other instances in which her ex has used or appeared to use technology to stalk her, but so far this hasn’t helped her get full custody of her children. The court’s failure to recognize these tech-facilitated tactics for maintaining power and control has left her frustrated to the point where she yearns for visible bruises. “I wish he was breaking my arms and punching me in the face,” she says, “because then people could see it.”

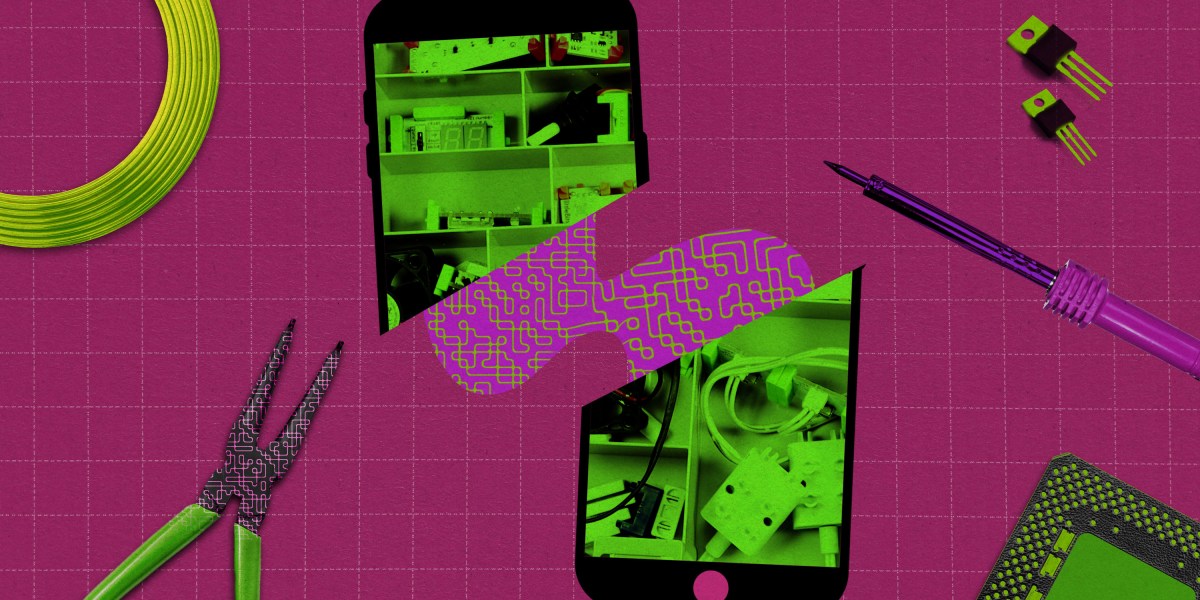

People I spoke with for this article described combating tech-facilitated abuse as playing “whack-a-mole.” Just as you figure out how to alert people to smartphone location sharing, enter smart cars.

This sentiment is unfortunately common among people experiencing what’s become known as TFA, or tech-facilitated abuse. Defined by the National Network to End Domestic Violence as “the use of digital tools, online platforms, or electronic devices to control, harass, monitor, or harm someone,” these often invisible or below-the-radar methods include using spyware and hidden cameras; sharing intimate images on social media without consent; logging into and draining a partner’s online bank account; and using device-based location tracking, as Gioia’s ex did with their daughter’s smartwatch.

Because technology is so ubiquitous, TFA occurs in most cases of intimate partner violence. And those whose jobs entail protecting victims and survivors and holding abusive actors accountable struggle to get a handle on this multifaceted problem. An Australian study from October 2024, which drew on in-depth interviews with victims and survivors of TFA, found a “considerable gap” in the understanding of TFA among frontline workers like police and victim service providers, with the result that police repeatedly dismissed TFA reports and failed to identify such incidents as examples of intimate partner violence. The study also identified a significant shortage of funding for specialists—that is, computer scientists skilled in conducting safety scans on the devices of people experiencing TFA.

The dearth of understanding is particularly concerning because keeping up with the many faces of tech-facilitated abuse requires significant expertise and vigilance. As internet-connected cars and homes become more common and location tracking is increasingly normalized, novel opportunities are emerging to use technology to stalk and harass. In reporting this piece, I heard chilling tales of abusers who remotely locked partners in their own “smart homes,” sometimes turning up the heat for added torment. One woman who fled her abusive partner found an ominous message when she opened her Netflix account miles away: “Bitch I’m Watching You” spelled out where the names of the accounts’ users should be.

Despite the range of tactics, a 2022 survey of TFA-focused studies across a number of English-speaking countries found that the results readily map onto the Power and Control Wheel, a tool developed in Duluth, Minnesota, in the 1980s that categorizes the all-encompassing ways abusive partners exert power and control over victims: economically, emotionally, through threats, using children, and more. Michaela Rogers, the lead author of the study and a senior lecturer at the University of Sheffield in the UK, says she noted “paranoia, anxiety, depression, trauma and PTSD, low self-esteem … and self-harm” among TFA survivors in the wake of abuse that often pervaded every aspect of their lives.

This kind of abuse is taxing and tricky to resolve alone. Service providers and victim advocates strive to help, but many lack tech skills, and they can’t stop tech companies from bringing products to market. Some work with those companies to help create safeguards, but there are limits to what businesses can do to hold abusive actors accountable. To establish real guardrails and dole out serious consequences, robust legal frameworks are needed.

It’s been slow work, but there have been concerted efforts to address TFA at each of these levels in the past couple of years. Some US states have passed laws against using smart car technology or location trackers such as Apple AirTags for stalking and harassment. Tech companies, including Apple and Meta, have hired people with experience in victim services to guide development of product safeguards, and advocates for victims and survivors are seeking out more specialized tech education.

But the ever-evolving nature of technology makes it nearly impossible to create a permanent fix. People I spoke with for this article described the effort as playing “whack-a-mole.” Just as you figure out how to alert people to smartphone location sharing, enter smart cars. Outlaw AirTag stalking and a newer, more effective tool appears that can legally track your ex. That’s why groups that uniquely address TFA, like the Clinic to End Tech Abuse (CETA) at Cornell Tech in New York City, are working to create permanent infrastructure. A problem that has typically been seen as a side focus for service organizations can finally get the treatment it deserves as a ubiquitous and potentially life-endangering aspect of intimate partner violence.

Volunteer tech support

CETA saw its first client seven years ago. In a small white room on Cornell Tech’s Roosevelt Island campus, two computer scientists sat down with someone whose abuser had been accessing the photos on their iPhone. The person didn’t know how this was happening.

“We worked with our client for about an hour and a half,” says one of the scientists, Thomas Ristenpart, “and realized it was probably an iCloud Family Sharing issue.”

At the time, CETA was one of just two clinics in the country created to address TFA (the other being the Technology Enabled Coercive Control Clinic in Seattle), and it remains on the cutting edge of the issue.

Picture a Venn diagram, with one circle representing computer scientists and the other service providers for domestic violence victims. It’s practically two separate circles, with CETA occupying a thin overlapping slice. Tech experts are much more likely to be drawn to profitable companies or research institutions than social-work nonprofits, so it’s unexpected that a couple of academic researchers identified TFA as a problem and chose to dedicate their careers to combating it. Their work has won results, but the learning curve was steep.

CETA grew out of an interest in measuring the “internet spyware software ecosystem” exploited in intimate partner violence, says Ristenpart. He and cofounder Nicola Dell initially figured they could help by building a tool that could scan phones for intrusive software. They quickly realized that this alone wouldn’t solve the problem—and could even compromise people’s safety if done carelessly, since it could alert abusers that their surveillance had been detected and was actively being thwarted.

Instead, Dell and Ristenpart studied the dynamics of coercive control. They conducted about 14 focus groups with professionals who worked daily with victims and survivors. They connected with organizations like the Anti-Violence Project and New York’s Family Justice Centers to get referrals. With the covid-19 pandemic, CETA went virtual and stayed that way. Its services now resemble “remote tech support,” Dell says. A handful of volunteers, many of whom work in Big Tech, receive clients’ intake information and guide them through processes for stopping unwanted location sharing, for example, on their devices.

Remote support has sufficed because abusers generally aren’t carrying out the type of sophisticated attack that can be foiled only by disassembling a device. “For the most part, people are using standard tools in the way that they were designed to be used,” says Dell. For example, someone might throw an AirTag into a stroller to keep track of its whereabouts (and those of the person pushing it), or act as the admin of a shared online bank account.

Though CETA stands out as a tech-centric service organization for survivors, anti-domestic-violence groups have been encountering and combating TFA for decades. When Cindy Southworth started her career in the domestic violence field in the 1990s, she heard of abusers doing rough location tracking using car odometers—the mileage could suggest, for instance, that a driver pretending to set out for the supermarket had instead left town to seek support. Later, when Southworth joined the Pennsylvania Coalition Against Domestic Violence, the advocacy community was looking at caller ID as “not only an incredibly powerful tool for survivors to be able to see who’s calling,” she recalls, “but also potentially a risky technology, if an abuser could see.”

As technology evolved, the ways abusers took advantage evolved too. Realizing that the advocacy community “was not up on tech,” Southworth founded the National Network to End Domestic Violence’s Safety Net Project in 2000 to provide a comprehensive training curriculum on how to “harness [technology] to help victims” and hold abusers accountable when they misuse it. Today, the project offers resources on its website, like tool kits that include guidance on strategies such as creating strong passwords and security questions. “When you’re in a relationship with someone,” explains director Audace Garnett, “they may know your mother’s maiden name.”

Big Tech safeguards

Southworth’s efforts later extended to advising tech companies on how to protect users who have experienced intimate partner violence. In 2020, she joined Facebook (now Meta) as its head of women’s safety. “What really drew me to Facebook was the work on intimate image abuse,” she says, noting that the company had come up with one of the first “sextortion” policies in 2012. Now she works on “reactive hashing,” which adds “digital fingerprints” to images that have been identified as nonconsensual so that survivors only need to report them once for all repeats to get blocked.

Other areas of concern include “cyberflashing,” in which someone might share, say, unwanted explicit photos. Meta has worked to prevent that on Instagram by not allowing accounts to send images, videos, or voice notes unless they follow you. Besides that, though, many of Meta’s practices surrounding potential abuse appear to be more reactive than proactive. The company says it removes online threats that violate its policies against bullying and that promote “offline violence.” But earlier this year, Meta made its policies about speech on its platforms more permissive. Now users are allowed to refer to women as “household objects,” reported CNN, and to post transphobic and homophobic comments that had formerly been banned.

A key challenge is that the very same tech can be used for good or evil: A tracking function that’s dangerous for someone whose partner is using it to stalk them might help someone else stay abreast of a stalker’s whereabouts. When I asked sources what tech companies should be doing to mitigate technology-assisted abuse, researchers and lawyers alike tended to throw up their hands. One cited the problem of abusers using parental controls to monitor adults instead of children—tech companies won’t do away with those important features for keeping children safe, and there is only so much they can do to limit how customers use or misuse them. Safety Net’s Garnett said companies should design technology with safety in mind “from the get-go” but pointed out that in the case of many well-established products, it’s too late for that. A couple of computer scientists pointed to Apple as a company with especially effective security measures: Its closed ecosystem can block sneaky third-party apps and alert users when they’re being tracked. But these experts also acknowledged that none of these measures are foolproof.

Over roughly the past decade, major US-based tech companies including Google, Meta, Airbnb, Apple, and Amazon have launched safety advisory boards to address this conundrum. The strategies they have implemented vary. At Uber, board members share feedback on “potential blind spots” and have influenced the development of customizable safety tools, says Liz Dank, who leads work on women’s and personal safety at the company. One result of this collaboration is Uber’s PIN verification feature, in which riders have to give drivers a unique number assigned by the app in order for the ride to start. This ensures that they’re getting into the right car.

Apple’s approach has included detailed guidance in the form of a 140-page “Personal Safety User Guide.” Under one heading, “I want to escape or am considering leaving a relationship that doesn’t feel safe,” it provides links to pages about blocking and evidence collection and “safety steps that include unwanted tracking alerts.”

Creative abusers can bypass these sorts of precautions. Recently Elizabeth (for privacy, we’re using her first name only) found an AirTag her ex had hidden inside a wheel well of her car, attached to a magnet and wrapped in duct tape. Months after the AirTag debuted, Apple had received enough reports about unwanted tracking to introduce a security measure letting users who’d been alerted that an AirTag was following them locate the device via sound. “That’s why he’d wrapped it in duct tape,” says Elizabeth. “To muffle the sound.”

Laws play catch-up

If tech companies can’t police TFA, law enforcement should—but its responses vary. “I’ve seen police say to a victim, ‘You shouldn’t have given him the picture,’” says Lisa Fontes, a psychologist and an expert on coercive control, about cases where intimate images are shared nonconsensually. When people have brought police hidden “nanny cams” planted by their abusers, Fontes has heard responses along the lines of “You can’t prove he bought it [or] that he was actually spying on you. So there’s nothing we can do.”

Places like the Queens Family Justice Center in New York City aim to remedy these law enforcement challenges. Navigating its mazelike halls, you can’t avoid bumping into a mix of attorneys, social workers, and case managers—which I did when executive director Susan Jacob showed me around after my visit to CETA. That’s by design. The center, one of more than 100 throughout the US, provides multiple services for those affected by gender-based and domestic violence. As I left, I passed a police officer escorting a man in handcuffs.

CETA is in the process of moving its services here—and then to centers in the city’s other four boroughs. Having tech clinics at these centers will put the techies right next to lawyers who may be prosecuting cases. It’s tricky to prove the identity of people connected with anonymous forms of tech harassment like social media posts and spoofed phone calls, but the expert help could make it easier for lawyers to build cases for search warrants and protection orders.

Law enforcement’s responses to allegations of tech-facilitated abuse vary. “I’ve seen police say to a victim, ‘You shouldn’t have given him the picture.’”

Lisa Fontes, psychologist and expert on coercive control

Lawyers pursuing cases with tech components don’t always have the legal framework to back them up. But laws in most US states do prohibit remote, covert tracking and the nonconsensual sharing of intimate images, while laws relating to privacy invasion, computer crimes, and stalking might cover aspects of TFA. In December, Ohio passed a law making AirTag stalking a crime, and Florida is considering an amendment that would increase penalties for people who use tracking devices to “commit or facilitate commission of dangerous crimes.” But keeping up with evolving tech requires additional legal specificity. “Tech comes first,” explains Lindsey Song, associate program director of the Queens center’s family law project. “People use it well. Abusers figure out how to misuse it. The law and policy come way, way, way later.”

California is leading the charge in legislation addressing harassment via smart vehicles. Signed into law in September 2024, Senate Bill 1394 requires connected vehicles to notify users if someone has accessed their systems remotely and provide a way for drivers to stop that access. “Many lawmakers were shocked to learn how common this problem is,” says Akilah Weber Pierson, a state senator who coauthored the bill. “Once I explained how survivors were being stalked or controlled through features designed for convenience, there was a lot of support.”

At the federal level, the Safe Connections Act signed into law in 2022 requires mobile service providers to honor survivors’ requests to separate from abusers’ plans. As of 2024, the Federal Communications Commission has been examining how to incorporate smart-car-facilitated abuse into the act’s purview. And in May, President Trump signed a bill prohibiting the online publication of sexually explicit images without consent. But there has been little progress on other fronts. The Tech Safety for Victims of Domestic Violence, Dating Violence, Sexual Assault, and Stalking Act would have authorized a pilot program, run by the Justice Department’s Office on Violence Against Women, to create as many as 15 TFA clinics for survivors. But since its introduction in the House of Representatives in November 2023, the bill has gone nowhere.

Tech abuse isn’t about tech

With changes happening so slowly at the legislative level, it remains largely up to folks on the ground to protect survivors from TFA. Rahul Chatterjee, an assistant professor of computer science at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, has taken a particularly hands-on approach. In 2021, he founded the Madison Tech Clinic after working at CETA as a graduate student. He and his team are working on a physical tool that can detect hidden cameras and other monitoring devices. The aim is to use cheap hardware like Raspberry Pis and ESP32s to keep it affordable.

Chatterjee has come across products online that purport to provide such protection, like radio frequency monitors for the impossibly low price of $20 and red-light devices claiming to detect invisible cameras. But they’re “snake oil,” he says. “We test them in the lab, and they don’t work.”

With the Trump administration slashing academic funding, folks who run tech clinics have expressed concern about sustainability. Dell, at least, received $800,000 from the MacArthur Foundation in 2024, some of which she plans to put toward launching new CETA-like clinics. The tech clinic in Queens got some seed funding from CETA for its first year, but it is “actively seeking fundraising to continue the program,” says Jennifer Friedman, a lawyer with the nonprofit Sanctuary for Families, which is overseeing the clinic.

While these clinics expose all sorts of malicious applications of technology, the moral of this story isn’t that you should fear your tech. It’s that people who aim to cause harm will take advantage of whatever new tools are available.

“[TFA] is not about the technology—it’s about the abuse,” says Garnett. “With or without the technology, the harm can still happen.” Ultimately, the only way to stem gender-based and intimate partner violence is at a societal level, through thoughtful legislation, amply funded antiviolence programs, and academic research that makes clinics like CETA possible.

In the meantime, to protect themselves, survivors like Gioia make do with Band-Aid fixes. She bought her kids separate smartphones and sports gear to use at her house so her ex couldn’t slip tracking devices into the equipment he’d provided. “I’m paying extra,” she says, “so stuff isn’t going back and forth.” She got a new number and a new phone.

“Believe the people that [say this is happening to them],” she says, “because it’s going on, and it’s rampant.”

Jessica Klein is a Philadelphia-based freelance journalist covering intimate partner violence, cryptocurrency, and other topics.