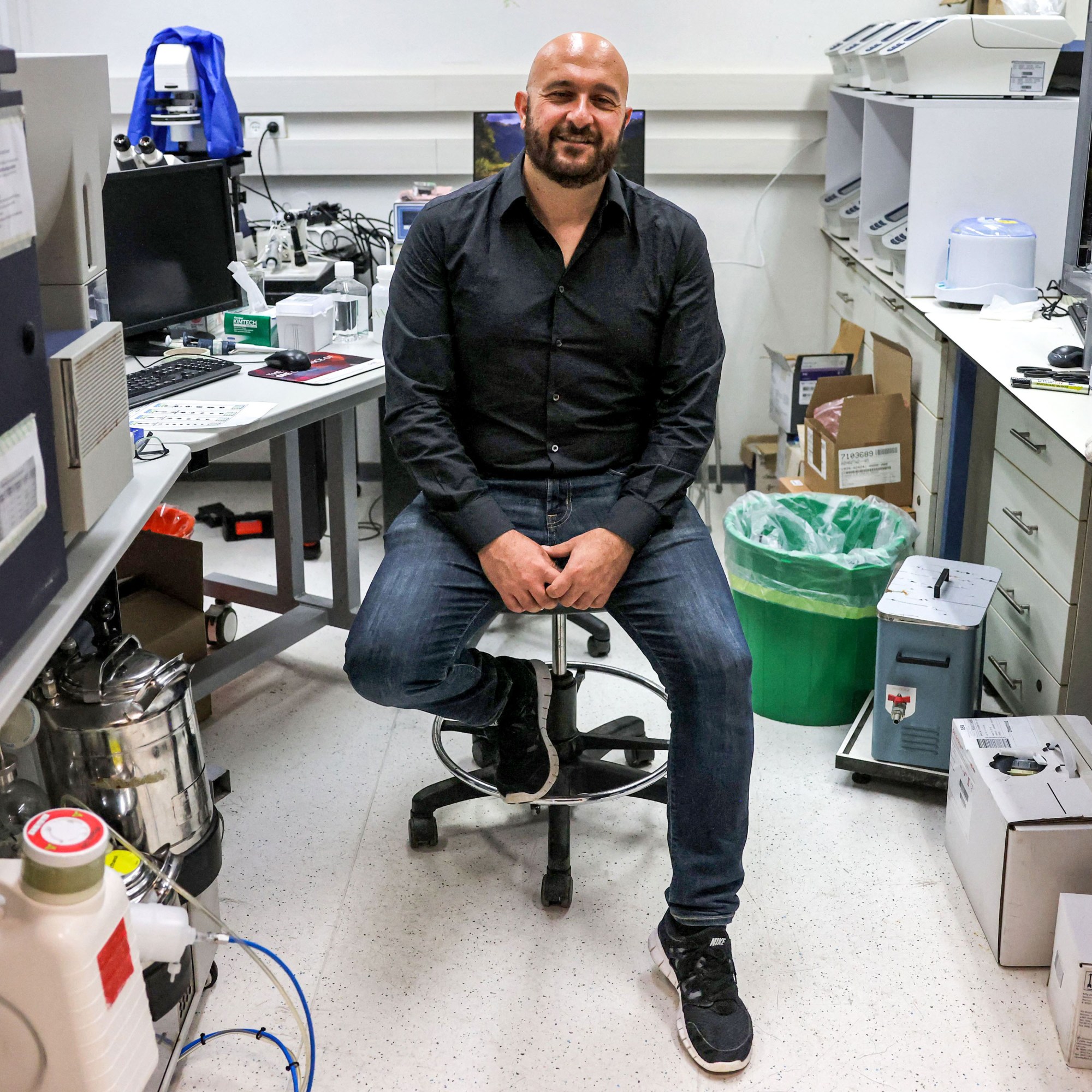

David Maimon is head of fraud insights at SentiLink.

Utility companies have become prime targets for identity-related fraud, yet the true scope of the threat remains largely hidden.

In 2024, the FTC’s Consumer Sentinel Network logged about 28,000 reports of stolen identities used to open new utility accounts and another 2,000 tied to existing ones. Those numbers exceed pre-COVID levels but fall short of a pandemic-era spike.

At first glance, that looks like stabilization. It’s not.

The reality is worse: Utilities are not legally required to report fraud incidents, leaving much of the damage invisible. Instead, companies push customers to file complaints — something many never do, whether because the utility absorbs the loss, the consumer avoids the hassle, or, in the case of synthetic identities, no real victim exists to file at all.

My research shows that the use of both stolen and synthetic identities to defraud utilities is persistent — and growing. Below I explain why utilities are prime targets, the tactics fraudsters use and how these crimes ripple across the broader fraud ecosystem.

Why utilities?

Utility providers are attractive targets for a mix of technical, regulatory and structural reasons.

- Low-friction onboarding: Compared to banks, many utilities still use limited identity verification. In the absence of strong “know your customer” rules, criminals can easily open accounts using stolen or synthetic identities.

- Delayed detection: Billing cycles stretch 30 to 60 days, giving scammers weeks of service before red flags appear. Fraudsters often exploit this delay and abandon accounts before utilities catch on.

- Service protections: Shutoff moratoriums — implemented during extreme weather or for medical “critical care” designations — protect vulnerable populations, but also shield fraudsters from enforcement. Once flagged as critical care, accounts can be nearly impossible to shut off even when fraud is suspected.

- Low legal risk: Utilities are not required to file suspicious activity reports and law enforcement deprioritizes unpaid bill cases. Electricity and gas are essential commodities with resale value, making accounts useful for scams, subleases and identity building.

For criminals, utility fraud offers free service, opportunities to resell or rent accounts and a low-risk testing ground for synthetic identities.

How fraudsters target utility providers

Using basic personal details like name, date of birth and social security number, fraudsters can open accounts, use service and then vanish, leaving the bill to the consumer or utility. Victims often discover the fraud only after collections appear on their credit reports.

Synthetic identities — blends of real and fabricated data — are increasingly used to secure utility accounts. Fraudsters often make small payments to establish legitimacy before running up large balances and disappearing in a classic “bust-out.”

Fraudsters also use stolen credit cards or bank account information to pay delinquent bills. These payments make fraudulent accounts look legitimate, boosting synthetic identities’ credibility. Underground forums openly advertise “bill payment” services at steep discounts, using stolen credentials to launder money through utility portals.

Many utilities run referral programs that reward new signups. Fraudsters create networks of fake accounts, all pointing back to a single “referrer.” The result is real payouts to fake customers and no long-term value for the utility.

Utility bills also serve as proof of address in broader fraud schemes. Once an account — real or fake — is opened, the bill becomes a useful artifact to apply for loans, rent apartments or onboard with fintechs. Fake bills are also widely sold online, complete with logos and billing histories.

Fraudsters even showcase stolen or forged utility bills in underground markets to prove their inventory’s quality. Investigators have traced these documents to synthetic identities later used in bank or credit applications. In one case, a fake utility bill dated October 2022 was linked to a neo-bank application filed the same month.

Why it matters

Utility fraud doesn’t just lead to unpaid bills. It acts as a gateway crime enabling fraudsters to simulate legitimate behavior, build credit histories or establish synthetic identities that later infiltrate banks, fintechs and government programs. Every fraudulent utility account is both a direct loss for providers and a stepping stone for larger crimes.

Meeting this challenge requires utilities take a layered, proactive approach:

- Stronger onboarding verification: Adopt tools such as device fingerprinting, phone/email risk scoring and identity-link analysis to detect anomalies at account opening.

- Synthetic identity monitoring: Watch for payment patterns consistent with bust-outs.

- Audit referral programs: Limit exploitation by tightening controls and monitoring for duplicate or suspicious accounts.

- Post-onboarding monitoring: Flag unusual usage or payment patterns that suggest fraud.

- Cross-provider data sharing: Collaborate across utilities to identify repeat offenders and track broader fraud trends.

Fraud is evolving, and utilities are increasingly in the crosshairs. What appears at first to be a modest rise in FTC-reported complaints is in reality a hidden, systemic problem, magnified by underreporting and the absence of regulatory oversight. Stolen and synthetic identities are flowing through utility systems not just for free electricity or gas, but to fuel broader fraud schemes that ripple across the financial sector.

Utilities need to evolve just as quickly — tightening verification, monitoring patterns and sharing intelligence — to protect both their own operations and the consumers who depend on them.

Fraudsters already see utility accounts as valuable financial infrastructure. The question is whether utilities will act before the problem grows even bigger.