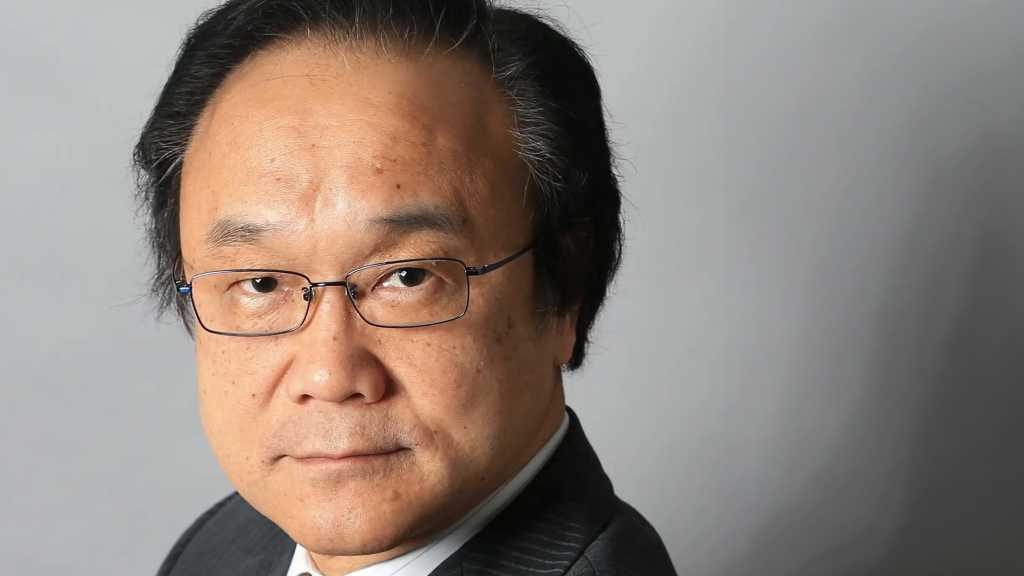

Mustafa Suleyman, CEO of Microsoft AI, is trying to walk a fine line. On the one hand, he thinks that the industry is taking AI in a dangerous direction by building chatbots that present as human: He worries that people will be tricked into seeing life instead of lifelike behavior. In August, he published a much-discussed post on his personal blog that urged his peers to stop trying to make what he called “seemingly conscious artificial intelligence,” or SCAI.

On the other hand, Suleyman runs a product shop that must compete with those peers. Last week, Microsoft announced a string of updates to its Copilot chatbot, designed to boost its appeal in a crowded market in which customers can pick and choose between a pantheon of rival bots that already includes ChatGPT, Perplexity, Gemini, Claude, DeepSeek, and more.

I talked to Suleyman about the tension at play when it comes to designing our interactions with chatbots and his ultimate vision for what this new technology should be.

One key Copilot update is a group-chat feature that lets multiple people talk to the chatbot at the same time. A big part of the idea seems to be to stop people from falling down a rabbit hole in a one-on-one conversation with a yes-man bot. Another feature, called Real Talk, lets people tailor how much Copilot pushes back on you, dialing down the sycophancy so that the chatbot challenges what you say more often.

Copilot also got a memory upgrade, so that it can now remember your upcoming events or long-term goals and bring up things that you told it in past conversations. And then there’s Mico, an animated yellow blob—a kind of Chatbot Clippy—that Microsoft hopes will make Copilot more accessible and engaging for new and younger users.

Microsoft says the updates were designed to make Copilot more expressive, engaging, and helpful. But I’m curious how far those features can be pushed without starting down the SCAI path that Suleyman has warned about.

Suleyman’s concerns about SCAI come at a time when we are starting to hear more and more stories about people being led astray by chatbots that are too engaging, too expressive, too helpful. OpenAI is being sued by the parents of a teenager who they allege was talked into killing himself by ChatGPT. There’s even a growing scene that celebrates romantic relationships with chatbots.

With all that in mind, I wanted to dig a bit deeper into Suleyman’s views. Because a couple of years ago he gave a TED Talk in which he told us that the best way to think about AI is as a new kind of digital species. Doesn’t that kind of hype feed the misperceptions Suleyman is now concerned about?

In our conversation, Suleyman told me what he was trying to get across in that TED Talk, why he really believes SCAI is a problem, and why Microsoft would never build sex robots (his words). He had a lot of answers, but he left me with more questions.

Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

In an ideal world, what kind of chatbot do you want to build? You’ve just launched a bunch of updates to Copilot. How do you get the balance right when you’re building a chatbot that has to compete in a market in which people seem to value humanlike interaction, but you also say you want to avoid seemingly conscious AI?

It’s a good question. With group chat, this will be the first time that a large group of people will be able to speak to an AI at the same time. It really is a way of emphasizing that AIs shouldn’t be drawing you out of the real world. They should be helping you to connect, to bring in your family, your friends, to have community groups, and so on.

That is going to become a very significant differentiator over the next few years. My vision of AI has always been one where an AI is on your team, in your corner.

This is a very simple, obvious statement, but it isn’t about exceeding and replacing humanity—it’s about serving us. That should be the test of technology at every step. Does it actually, you know, deliver on the quest of civilization, which is to make us smarter and happier and more productive and healthier and stuff like that?

So we’re just trying to build features that constantly remind us to ask that question, and remind our users to push us on that issue.

Last time we spoke, you told me that you weren’t interested in making a chatbot that would role-play personalities. That’s not true of the wider industry. Elon Musk’s Grok is selling that kind of flirty experience. OpenAI has said it’s interested in exploring new adult interactions with ChatGPT. There’s a market for that. And yet this is something you’ll just stay clear of?

Yeah, we will never build sex robots. Sad in a way that we have to be so clear about that, but that’s just not our mission as a company. The joy of being at Microsoft is that for 50 years, the company has built, you know, software to empower people, to put people first.

Sometimes, as a result, that means the company moves slower than other startups and is more deliberate and more careful. But I think that’s a feature, not a bug, in this age, when being attentive to potential side effects and longer-term consequences is really important.

And that means what, exactly?

We’re very clear on, you know, trying to create an AI that fosters a meaningful relationship. It’s not that it’s trying to be cold and anodyne—it cares about being fluid and lucid and kind. It definitely has some emotional intelligence.

So where does it—where do you—draw those boundaries?

Our newest chat model, which is called Real Talk, is a little bit more sassy. It’s a bit more cheeky, it’s a bit more fun, it’s quite philosophical. It’ll happily talk about the big-picture questions, the meaning of life, and so on. But if you try and flirt with it, it’ll push back and it’ll be very clear—not in a judgmental way, but just, like: “Look, that’s not for me.”

There are other places where you can go to get that kind of experience, right? And I think that’s just a decision we’ve made as a company.

Is a no-flirting policy enough? Because if the idea is to stop people even imagining an entity, a consciousness, behind the interactions, you could still get that with a chatbot that wanted to keep things SFW. You know, I can imagine some people seeing something that’s not there even with a personality that’s saying, hey, let’s keep this professional.

Here’s a metaphor to try to make sense of it. We hold each other accountable in the workplace. There’s an entire architecture of boundary management, which essentially sculpts human behavior to fit a mold that’s functional and not irritating.

The same is true in our personal lives. The way that you interact with your third cousin is very different to the way you interact with your sibling. There’s a lot to learn from how we manage boundaries in real human interactions.

It doesn’t have to be either a complete open book of emotional sensuality or availability—drawing people into a spiraled rabbit hole of intensity—or, like, a cold dry thing. There’s a huge spectrum in between, and the craft that we’re learning as an industry and as a species is to sculpt these attributes.

And those attributes obviously reflect the values of the companies that design them. And I think that’s where Microsoft has a lot of strengths, because our values are pretty clear, and that’s what we’re standing behind.

A lot of people seem to like personalities. Some of the backlash to GPT-5, for example, was because the previous model’s personality had been taken away. Was it a mistake for OpenAI to have put a strong personality there in the first place, to give people something that they then missed?

No, personality is great. My point is that we’re trying to sculpt personality attributes in a more fine-grained way, right?

Like I said, Real Talk is a cool personality. It’s quite different to normal Copilot. We are also experimenting with Mico, which is this visual character, that, you know, people—some people—really love. It’s much more engaging. It’s easier to talk to about all kinds of emotional questions and stuff.

I guess this is what I’m trying to get straight. Features like Mico are meant to make Copilot more engaging and nicer to use, but it seems to go against the idea of doing whatever you can to stop people thinking there’s something there that you are actually having a friendship with.

Yeah. I mean, it doesn’t stop you necessarily. People want to talk to somebody, or something, that they like. And we know that if your teacher is nice to you at school, you’re going to be more engaged. The same with your manager, the same with your loved ones. And so emotional intelligence has always been a critical part of the puzzle, so it’s not to say that we don’t want to pursue it.

It’s just that the craft is in trying to find that boundary. And there are some things which we’re saying are just off the table, and there are other things which we’re going to be more experimental with. Like, certain people have complained that they don’t get enough pushback from Copilot—they want it to be more challenging. Other people aren’t looking for that kind of experience—they want it to be a basic information provider. The task for us is just learning to disentangle what type of experience to give to different people.

I know you’ve been thinking about how people engage with AI for some time. Was there an inciting incident that made you want to start this conversation in the industry about seemingly conscious AI?

I could see that there was a group of people emerging in the academic literature who were taking the question of moral consideration for artificial entities very seriously. And I think it’s very clear that if we start to do that, it would detract from the urgent need to protect the rights of many humans that already exist, let alone animals.

If you grant AI rights, that implies—you know—fundamental autonomy, and it implies that it might have free will to make its own decisions about things. So I’m really trying to frame a counter to that, which is that it won’t ever have free will. It won’t ever have complete autonomy like another human being.

AI will be able to take actions on our behalf. But these models are working for us. You wouldn’t want a pack of, you know, wolves wandering around that weren’t tame and that had complete freedom to go and compete with us for resources and weren’t accountable to humans. I mean, most people would think that was a bad idea and that you would want to go and kill the wolves.

Okay. So the idea is to stop some movement that’s calling for AI welfare or rights before it even gets going, by making sure that we don’t build AI that appears to be conscious? What about not building that kind of AI because certain vulnerable people may be tricked by it in a way that may be harmful? I mean, those seem to be two different concerns.

I think the test is going to be in the kinds of features the different labs put out and in the types of personalities that they create. Then we’ll be able to see how that’s affecting human behavior.

But is it a concern of yours that we are building a technology that might trick people into seeing something that isn’t there? I mean, people have claimed they’ve seen sentience inside far less sophisticated models than we have now. Or is that just something that some people will always do?

It’s possible. But my point is that a responsible developer has to do our best to try and detect these patterns emerging in people as quickly as possible and not take it for granted that people are going to be able to disentangle those kinds of experiences themselves.

When I read your post about seemingly conscious AI, I was struck by a line that says: “We must build AI for people; not to be a digital person.” It made me think of a TED Talk you gave last year where you say that the best way to think about AI is as a new kind of digital species. Can you help me understand why talking about this technology as a digital species isn’t a step down the path of thinking about AI models as digital persons or conscious entities?

I think the difference is that I’m trying to offer metaphors that make it easier for people to understand where things might be headed, and therefore how to avert that and how to control it.

Okay.

It’s not to say that we should do those things. It’s just pointing out that this is the emergence of a technology which is unique in human history. And if you just assume that it’s a tool or just a chatbot or a dumb— you know, I kind of wrote that TED Talk in the context of a lot of skepticism. And I think it’s important to be clear-eyed about what’s coming so that one can think about the right guardrails.

And yet, if you’re telling me this technology is a new digital species, I have some sympathy for the people who say, well, then we need to consider welfare.

I wouldn’t. [He starts laughing.] Just not in the slightest. No way. It’s not a direction that any of us want to go in.

No, that’s not what I meant. I don’t think chatbots should have welfare. I’m saying I’d have some sympathy for where such people were coming from when they hear, you know, Mustafa Suleyman tell them that this thing he’s building was a new digital species. I’d understand why they might then say that they wanted to stand up for it. I’m saying the words we use matter, I guess.

The rest of the TED Talk was all about how to contain AI and how not to let this species take over, right? That was the whole point of setting it up as, like, this is what’s coming. I mean, that’s what my whole book [The Coming Wave, published in 2023] was about—containment and alignment and stuff like that. There’s no point in pretending that it’s something that it’s not and then building guardrails and boundaries that don’t apply because you think it’s just a tool.

Honestly, it does have the potential to recursively self-improve. It does have the potential to set its own goals. Those are quite profound things. No other technology we’ve ever invented has that. And so, yeah, I think that it is accurate to say that it’s like a digital species, a new digital species. That’s what we’re trying to restrict to make sure it’s always in service of people. That’s the target for containment.