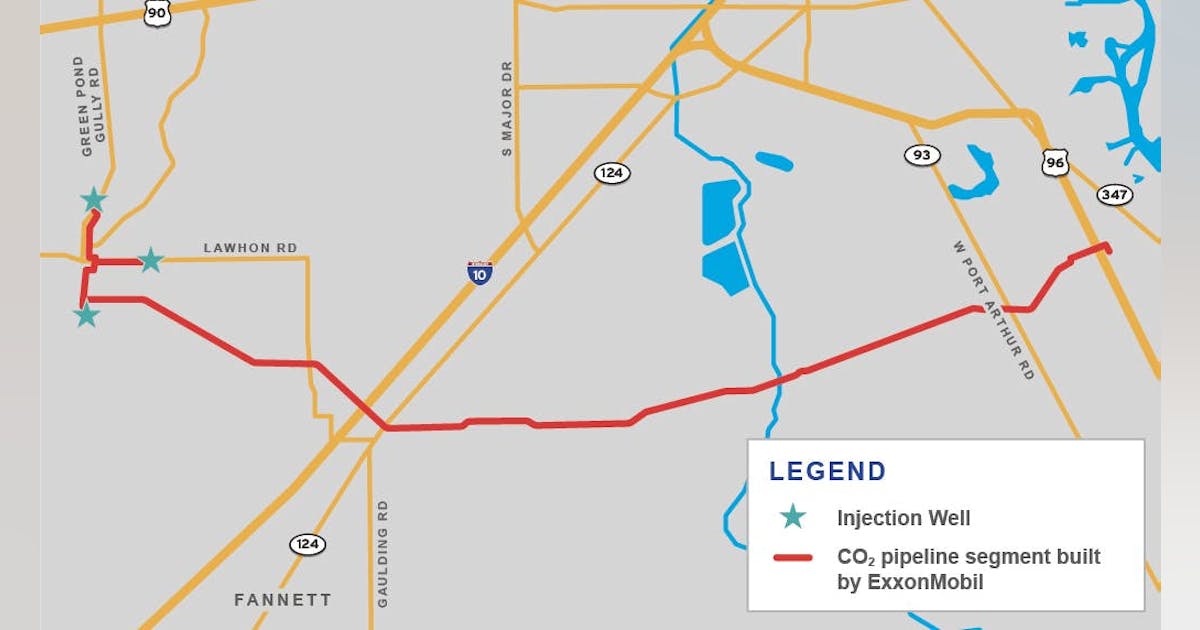

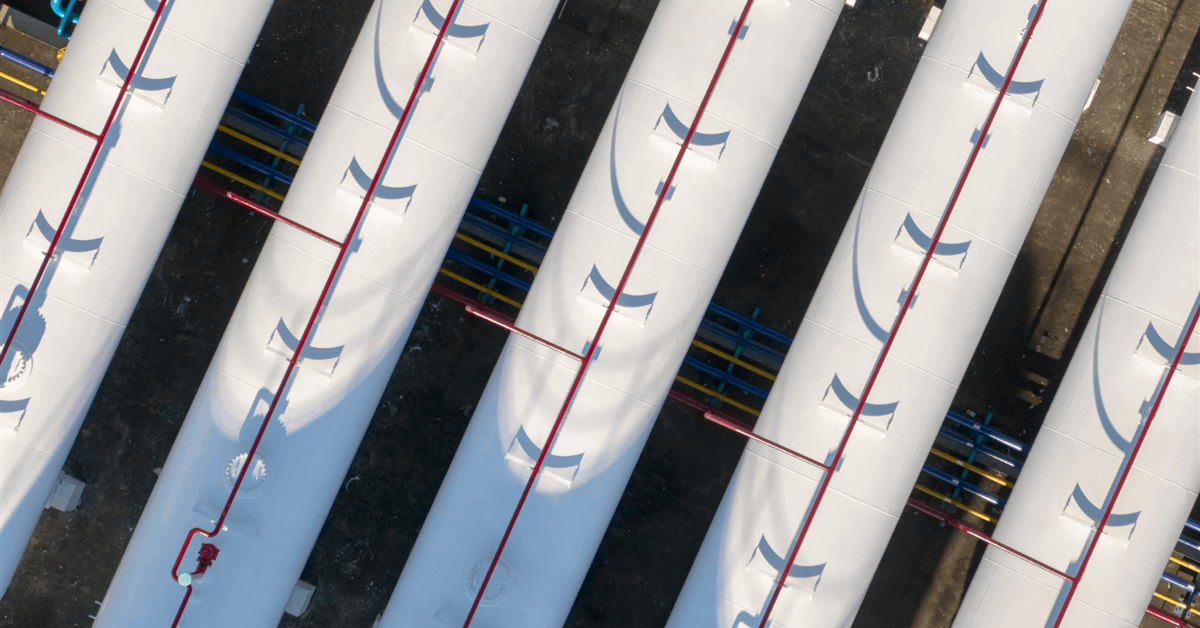

Rondo Energy just turned on what it says is the world’s largest thermal battery, an energy storage system that can take in electricity and provide a consistent source of heat.

The company announced last week that its first full-scale system is operational, with 100 megawatt-hours of capacity. The thermal battery is powered by an off-grid solar array and will provide heat for enhanced oil recovery (more on this in a moment).

Thermal batteries could help clean up difficult-to-decarbonize sectors like manufacturing and heavy industrial processes like cement and steel production. With Rondo’s latest announcement, the industry has reached a major milestone in its effort to prove that thermal energy storage can work in the real world. Let’s dig into this announcement, what it means to have oil and gas involved, and what comes next.

The concept behind a thermal battery is overwhelmingly simple: Use electricity to heat up some cheap, sturdy material (like bricks) and keep it hot until you want to use that heat later, either directly in an industrial process or to produce electricity.

Rondo’s new system has been operating for 10 weeks and achieved all the relevant efficiency and reliability benchmarks, according to the company. The bricks reach temperatures over 1,000 °C (about 1,800 °F), and over 97% of the energy put into the system is returned as heat.

This is a big step from the 2 MWh pilot system that Rondo started up in 2023, and it’s the first of the mass-produced, full-size heat batteries that the company hopes to put in the hands of customers.

Thermal batteries could be a major tool in cutting emissions: 20% of total energy demand today is used to provide heat for industrial processes, and most of that is generated by burning fossil fuels. So this project’s success is significant for climate action.

There’s one major detail here, though, that dulls some of that promise: This battery is being used for enhanced oil recovery, a process where steam is injected down into wells to get stubborn oil out of the ground.

It can be tricky for a climate technology to show its merit by helping harvest fossil fuels. Some critics argue that these sorts of techniques keep that polluting infrastructure running longer.

When I spoke to Rondo founder and chief innovation officer John O’Donnell about the new system, he defended the choice to work with oil and gas.

“We are decarbonizing the world as it is today,” O’Donnell says. To his mind, it’s better to help an oil and gas company use solar power for its operation than leave it to continue burning natural gas for heat. Between cheap solar, expensive natural gas, and policies in California, he adds, Rondo’s technology made sense for the customer.

Having a willing customer pay for a full-scale system has been crucial to Rondo’s effort to show that it can deliver its technology.

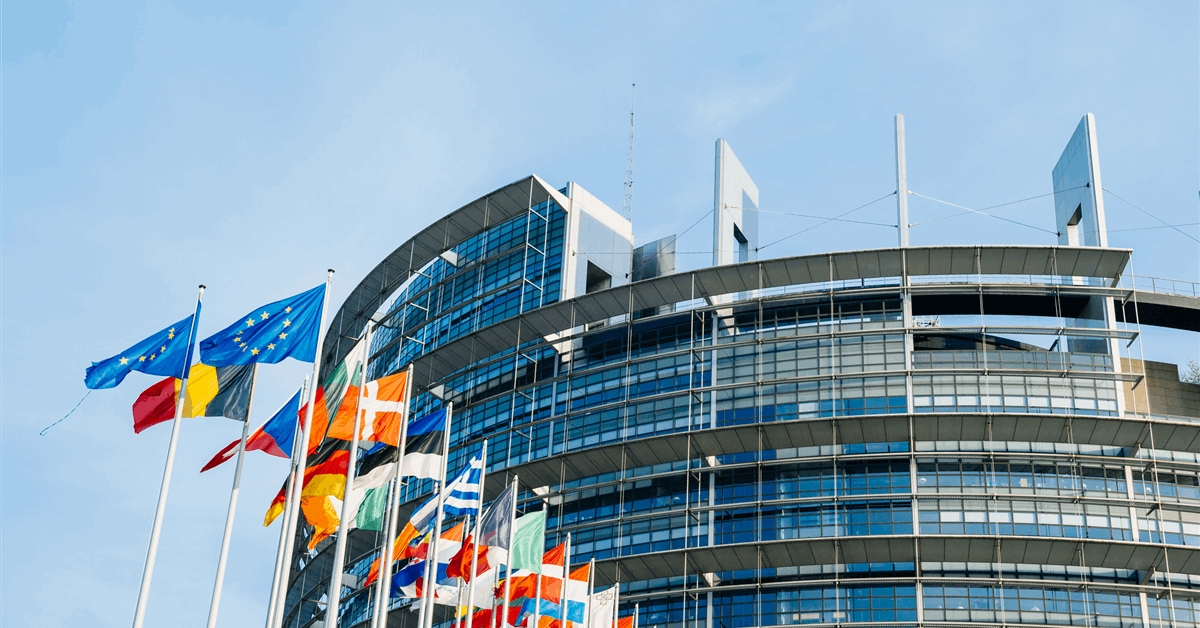

And the next units are on the way: Rondo is currently building three more full-scale units in Europe. The company will be able to bring them online cheaper and faster because of what it’s learned from the California project, O’Donnell says.

The company has the capacity to build more batteries, and do it quickly. It currently makes batteries at its factory in Thailand, which has the capacity to make 2.4 gigawatt-hours’ worth of heat batteries today.

I’ve been following progress on thermal batteries for years, and this project obviously represents a big step forward. For all the promises of cheap, robust energy storage, there’s nothing like actually building a large-scale system and testing it in the field.

It’s definitely hard to get excited about enhanced oil recovery—we need to stop burning fossil fuels, and do it quickly, to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. But I see the argument that as long as oil and gas operations exist, there’s value in cleaning them up.

And as O’Donnell puts it, heat batteries can help: “This is a really dumb, practical thing that’s ready now.”

This article is from The Spark, MIT Technology Review’s weekly climate newsletter. To receive it in your inbox every Wednesday, sign up here.