This week, I have a new story out about Quaise, a geothermal startup that’s trying to commercialize new drilling technology. Using a device called a gyrotron, the company wants to drill deeper, cheaper, in an effort to unlock geothermal power anywhere on the planet. (For all the details, check it out here.)

For the story, I visited Quaise’s headquarters in Houston. I also took a trip across town to Nabors Industries, Quaise’s investor and tech partner and one of the biggest drilling companies in the world.

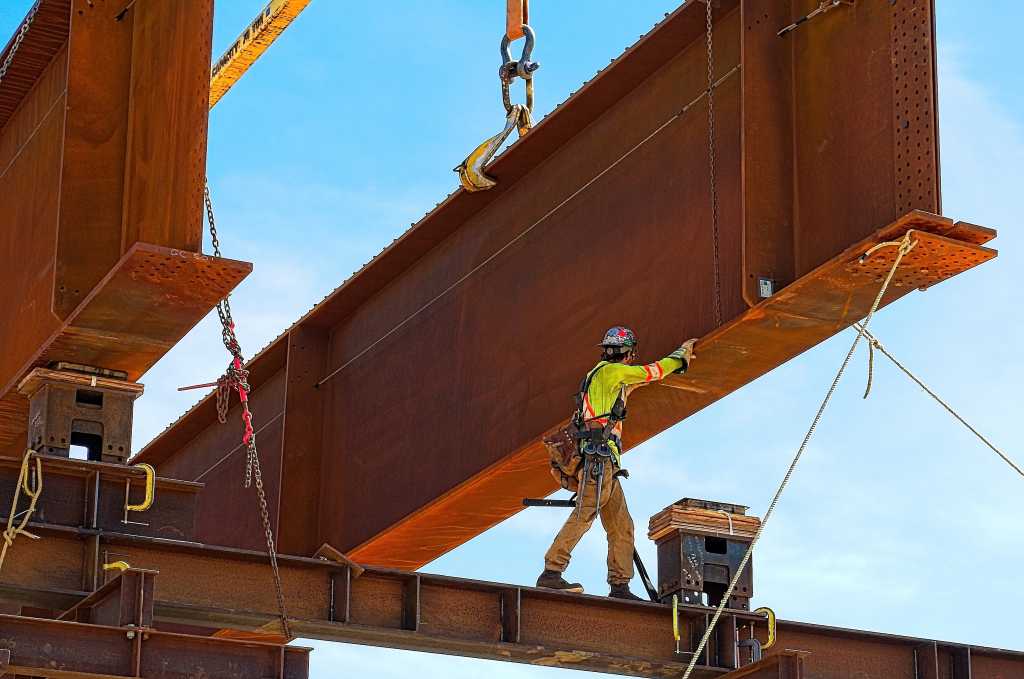

Standing on top of a drilling rig in the backyard of Nabors’s headquarters, I couldn’t stop thinking about the role oil and gas companies are playing in the energy transition. This industry has resources and energy expertise—but also a vested interest in fossil fuels. Can it really be part of addressing climate change?

The relationship between Quaise and Nabors is one that we see increasingly often in climate tech—a startup partnering up with an established company in a similar field. (Another one that comes to mind is in the cement industry, where Sublime Systems has seen a lot of support from legacy players including Holcim, one of the biggest cement companies in the world.)

Quaise got an early investment from Nabors in 2021, to the tune of $12 million. Now the company also serves as a technical partner for the startup.

“We are agnostic to what hole we’re drilling,” says Cameron Maresh, a project engineer on the energy transition team at Nabors Industries. The company is working on other investments and projects in the geothermal industry, Maresh says, and the work with Quaise is the culmination of a yearslong collaboration: “We’re just truly excited to see what Quaise can do.”

From the outside, this sort of partnership makes a lot of sense for Quaise. It gets resources and expertise. Meanwhile, Nabors is getting involved with an innovative company that could represent a new direction for geothermal. And maybe more to the point, if fossil fuels are to be phased out, this deal gives the company a stake in next-generation energy production.

There is so much potential for oil and gas companies to play a productive role in addressing climate change. One report from the International Energy Agency examined the role these legacy players could take: “Energy transitions can happen without the engagement of the oil and gas industry, but the journey to net zero will be more costly and difficult to navigate if they are not on board,” the authors wrote.

In the agency’s blueprint for what a net-zero emissions energy system could look like in 2050, about 30% of energy could come from sources where the oil and gas industry’s knowledge and resources are useful. That includes hydrogen, liquid biofuels, biomethane, carbon capture, and geothermal.

But so far, the industry has hardly lived up to its potential as a positive force for the climate. Also in that report, the IEA pointed out that oil and gas producers made up only about 1% of global investment in climate tech in 2022. Investment has ticked up a bit since then, but still, it’s tough to argue that the industry is committed.

And now that climate tech is falling out of fashion with the government in the US, I’d venture to guess that we’re going to see oil and gas companies increasingly pulling back on their investments and promises.

BP recently backtracked on previous commitments to cut oil and gas production and invest in clean energy. And last year the company announced that it had written off $1.1 billion in offshore wind investments in 2023 and wanted to sell other wind assets. Shell closed down all its hydrogen fueling stations for vehicles in California last year. (This might not be all that big a loss, since EVs are beating hydrogen by a huge margin in the US, but it’s still worth noting.)

So oil and gas companies are investing what amounts to pennies and often backtrack when the political winds change direction. And, let’s not forget, fossil-fuel companies have a long history of behaving badly.

In perhaps the most notorious example, scientists at Exxon modeled climate change in the 1970s, and their forecasts turned out to be quite accurate. Rather than publish that research, the company downplayed how climate change might affect the planet. (For what it’s worth, company representatives have argued that this was less of a coverup and more of an internal discussion that wasn’t fit to be shared outside the company.)

While fossil fuels are still part of our near-term future, oil and gas companies, and particularly producers, would need to make drastic changes to align with climate goals—changes that wouldn’t be in their financial interest. Few seem inclined to really take the turn needed.

As the IEA report puts it: “In practice, no one committed to change should wait for someone else to move first.”

This article is from The Spark, MIT Technology Review’s weekly climate newsletter. To receive it in your inbox every Wednesday, sign up here.