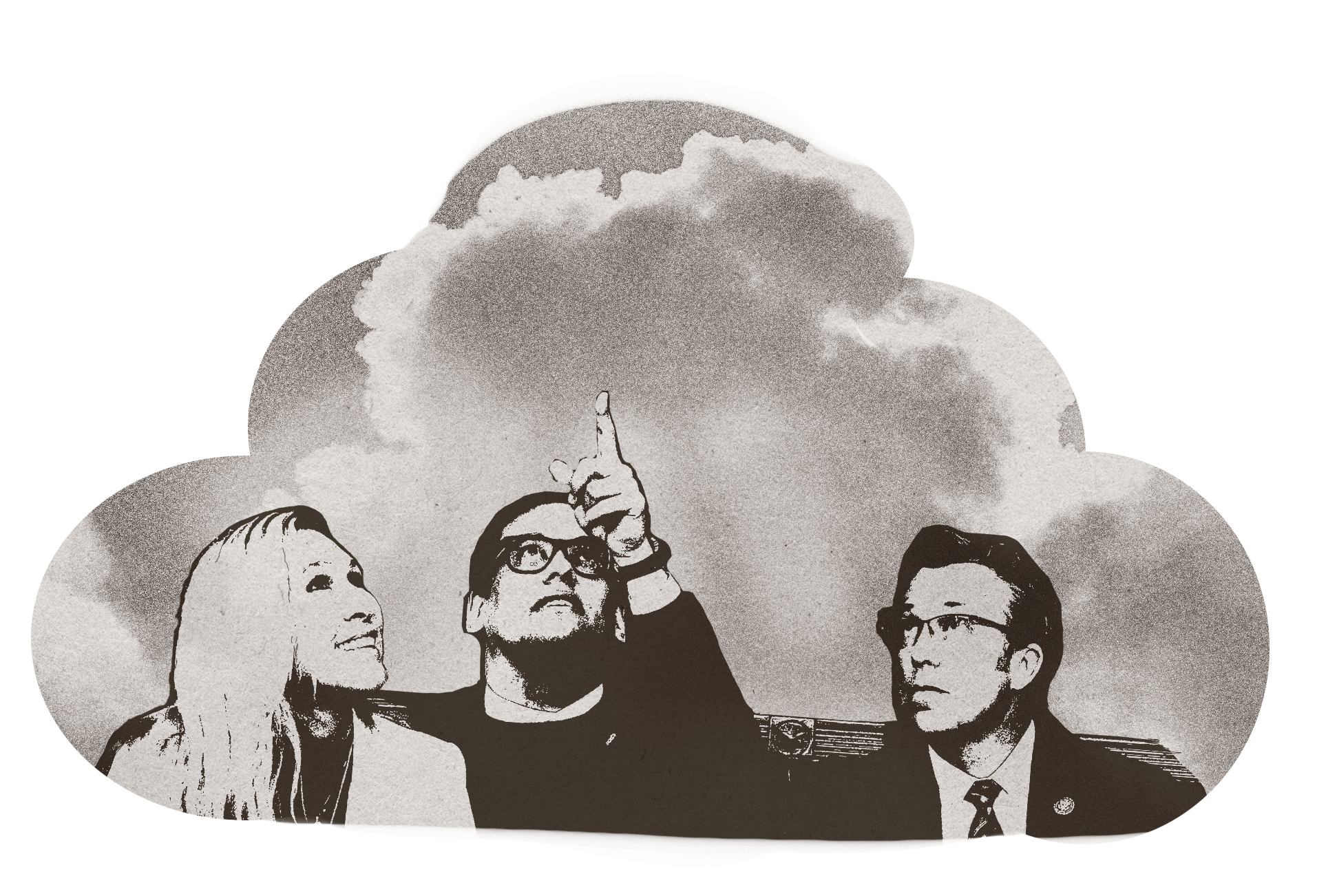

It was October 2024, and Hurricane Helene had just devastated the US Southeast. Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia found an abstract target on which to pin the blame: “Yes they can control the weather,” she posted on X. “It’s ridiculous for anyone to lie and say it can’t be done.”

There was no word on who “they” were, but maybe it was better that way.

She was repeating what’s by now a pretty familiar and popular conspiracy theory: that shadowy forces are out there, wielding unknown technology to control the weather and wreak havoc on their supposed enemies. This claim, fundamentally preposterous from a scientific standpoint, has grown louder and more common in recent years. It pops up over and over when extreme weather strikes: in Dubai in April 2024, in Australia in July 2022, in the US after California floods and hurricanes like Helene and Milton. In the UK, conspiracy theorists claimed that the government had fixed the weather to be sunny and rain-free during the first covid lockdown in March 2020. Most recently, the theories spread again when disastrous floods hit central Texas this past July. The idea has even inspired some antigovernment extremists to threaten and try to destroy weather radar towers.

This story is part of MIT Technology Review’s series “The New Conspiracy Age,” on how the present boom in conspiracy theories is reshaping science and technology.

But here’s the thing: While Greene and other believers are not correct, this conspiracy theory—like so many others—holds a kernel of much more modest truth behind the grandiose claims.

Sure, there is no current way for humans to control the weather. We can’t cause major floods or redirect hurricanes or other powerful storm systems, simply because the energy involved is far too great for humans to alter significantly.

But there are ways we can modify the weather. The key difference is the scale of what is possible.

The most common weather modification practice is called cloud seeding, and it involves injecting small amounts of salts or other materials into clouds with the goal of juicing levels of rain or snow. This is typically done in dry areas that lack regular precipitation. Research shows that it can in fact work, though advances in technology reveal that its impact is modest—coaxing maybe 5% to 10% more moisture out of otherwise stubborn clouds.

But the fact that humans can influence weather at all gives conspiracy theorists a foothold in the truth. Add to this a spotty history of actual efforts by governments and militaries to control major storms, as well as other emerging but not-yet-deployed-at-any-scale technologies that aim to address climate change … and you can see where things get confusing.

So while more sweeping claims of weather control are ultimately ridiculous from a scientific standpoint, they can’t be dismissed as entirely stupid.

This all helped make the conspiracy theories swirling after the recent Texas floods particularly loud and powerful. Just days earlier, 100 miles away from the epicenter of the floods, in a town called Runge, the cloud-seeding company Rainmaker had flown a single-engine plane and released about 70 grams of silver iodide into some clouds; a modest drizzle of less than half a centimeter of rain followed. But once the company saw a storm front in the forecast, it suspended its work; there was no need to seed with rain already on the way.

“We conducted an operation on July 2, totally within the scope of what we were regulatorily permitted to do,” Augustus Doricko, Rainmaker’s founder and CEO, recently told me. Still, when as much as 20 inches of rain fell soon afterward not too far away, and more than 100 people died, the conspiracy theory machine whirred into action.

As Doricko told the Washington Post in the tragedy’s aftermath, he and his company faced “nonstop pandemonium” on social media; eventually someone even posted photos from outside Rainmaker’s office, along with its address. Doricko told me a few factors played into the pile-on, including a lack of familiarity with the specifics of cloud seeding, as well as what he called “deliberately inflammatory messaging from politicians.” Indeed, theories about Rainmaker and cloud seeding spread online via prominent figures including Greene and former national security advisor Mike Flynn.

Unfortunately, all this is happening at the same time as the warming climate is making heavy rainfall and the floods that accompany it more and more likely. “These events will become more frequent,” says Emily Yeh, a professor of geography at the University of Colorado who has examined approaches and reactions to weather modification around the world. “There is a large, vocal group of people who are willing to believe anything but climate change as the reason for Texas floods, or hurricanes.”

Worsening extremes, increasing weather modification activity, improving technology, a sometimes shady track record—the conditions are perfect for an otherwise niche conspiracy theory to spread to anyone desperate for tidy explanations of increasingly disastrous events.

Here, we break down just what’s possible and what isn’t—and address some of the more colorful reasons why people may believe things that go far beyond the facts.

What we can do with the weather—and who is doing it

The basic concepts behind cloud seeding have been around for about 80 years, and government interest in the topic goes back even longer than that.

The primary practice involves using planes, drones, or generators on the ground to inject tiny particles of stuff, usually silver iodide, into existing clouds. The particles act as nuclei around which moisture can build up, forming ice crystals that can get heavy enough to fall out of the cloud as snow or rain.

“Weather modification is an old field; starting in the 1940s there was a lot of excitement,” says David Delene, a research professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of North Dakota and an expert on cloud seeding. In a US Senate report from 1952 to establish a committee to study weather modification, authors noted that a small amount of extra rain could “produce electric power worth hundreds of thousands of dollars” and “greatly increase crop yields.” It also cited potential uses like “reducing soil erosion,” “breaking up hurricanes,” and even “cutting holes in clouds so that aircraft can operate.”

But, as Delene adds, “that excitement … was not realized.”

Through the 1980s, extensive research often funded or conducted by Washington yielded a much better understanding of atmospheric science and cloud physics, though it proved extremely difficult to actually demonstrate the efficacy of the technology itself. In other words, scientists learned the basic principles behind cloud seeding, and understood on a theoretical level that it should work—but it was hard to tell how big an impact it was having on rainfall.

There is huge variability between one cloud and another, one storm system and another, one mountain or valley and another; for decades, the tools available to researchers did not really allow for firm conclusions on exactly how much extra moisture, if any, they were getting out of any given operation. Interest in the practice died down to a low hum by the 1990s.

But over the past couple of decades, the early excitement has returned.

Cloud seeding can enhance levels of rain and snow

While the core technology has largely stayed the same, several projects launched in the US and abroad starting in the 2000s have combined statistical modeling with new and improved aircraft-based measurements, ground-based radar, and more to provide better answers on what results are actually achievable when seeding clouds.

“I think we’ve identified unequivocally that we can indeed modify the cloud,” says Jeff French, an associate professor and head of the University of Wyoming’s Department of Atmospheric Science, who has worked for years on the topic. But even as scientists have come to largely agree that the practice can have an impact on precipitation, they also largely recognize that the impact probably has some fairly modest upper limits—far short of massive water surges.

“There is absolutely no evidence that cloud seeding can modify a cloud to the extent that would be needed to cause a flood,” French says. Floods require a few factors, he adds—a system with plenty of moisture available that stays localized to a certain spot for an extended period. “All of these things which cloud seeding has zero effect on,” he says.

The technology simply operates on a different level. “Cloud seeding really is looking at making an inefficient system a little bit more efficient,” French says.

As Delene puts it: “Originally [researchers] thought, well, we could, you know, do 50%, 100% increases in precipitation,” but “I think if you do a good program you’re not going to get more than a 10% increase.”

Asked for his take on a theoretical limit, French was hesitant—“I don’t know if I’m ready to stick my neck out”—but agreed on “maybe 10-ish percent” as a reasonable guess.

Another cloud seeding expert, Katja Friedrich from the University of Colorado–Boulder, says that any grander potential would be obvious by this point: We wouldn’t have “spent the last 100 years debating—within the scientific community—if cloud seeding works,” she writes in an email. “It would have been easy to separate the signal (from cloud seeding) from the noise (natural precipitation).”

It can also (probably) suppress precipitation

Sometimes cloud seeding is used not to boost rain and snow but rather to try to reduce its severity—or, more specifically, to change the size of individual rain droplets or hailstones.

One of the most prominent examples has been in parts of Canada, where hailstorms can be devastating; a 2024 event in Calgary, for instance, was the country’s second-most-expensive disaster ever, with over $2 billion in damages.

Insurance companies in Alberta have been working together for nearly three decades on a cloud seeding program that’s aimed at reducing some of that damage. In these cases, the silver iodide or other particles are meant to act essentially as competition for other “embryos” inside the cloud, increasing the total number of hailstones and thus reducing each individual stone’s average size.

Smaller hailstones means less damage when they reach the ground. The insurance companies—which continue to pay for the program—say losses have been cut by 50% since the program started, though scientists aren’t quite as confident in its overall success. A 2023 study published in Atmospheric Research examined 10 years of cloud seeding efforts in the province and found that the practice did appear to reduce potential for damage in about 60% of seeded storms—while in others, it had no effect or was even associated with increased hail (though the authors said this could have been due to natural variation).

Similar techniques are also sometimes deployed to try to improve the daily forecast just a bit. During the 2008 Olympics, for instance, China engaged in a form of cloud seeding aimed at reducing rainfall. As MIT Technology Review detailed back then, officials with the Beijing Weather Modification Office planned to use a liquid-nitrogen-based coolant that could increase the number of water droplets in a cloud while reducing their size; this can get droplets to stay aloft a little longer instead of falling out of the cloud. Though it is tough to prove that it definitively would have rained without the effort, the targeted opening ceremony did stay dry.

So, where is this happening?

The United Nations’ World Meteorological Organization says that some form of weather modification is taking place in “more than 50 countries” and that “demand for these weather modification activities is increasing steadily due to the incidence of droughts and other calamities.”

The biggest user of cloud-seeding tech is arguably China. Following the work around the Olympics, the country announced a huge expansion of its weather modification program in 2020, claiming it would eventually run operations for agricultural relief and other functions, including hail suppression, over an area about the size of India and Algeria combined. Since then, China has occasionally announced bits of progress—including updates to weather modification aircraft and the first use of drones for artificial snow enhancement. Overall, it spends billions on the practice, with more to come.

Elsewhere, desert countries have taken an interest. In 2024, Saudi Arabia announced an expanded research program on cloud seeding—Delene, of the University of North Dakota, was part of a team that conducted experiments in various parts of that country in late 2023. Its neighbor the United Arab Emirates began “rain enhancement” activities back in 1990; this program too has faced outcry, especially after more than a typical year’s worth of rain fell in a single day in 2024, causing massive flooding. (Bloomberg recently published a story about persistent questions regarding the country’s cloud seeding program; in response to the story, French wrote in an email that the “best scientific understanding is still that cloud seeding CANNOT lead to these types of events.” Other experts we asked agreed.)

In the US, a 2024 Government Accountability Office report on cloud seeding said that at least nine states have active programs. These are sometimes run directly by the state and sometimes contracted out through nonprofits like the South Texas Weather Modification Association to private companies, including Doricko’s Rainmaker and North Dakota–based Weather Modification. In August, Doricko told me that Rainmaker had grown to 76 employees since it launched in 2023. It now runs cloud seeding operations in Utah, Idaho, Oregon, California, and Texas, as well as forecasting services in New Mexico and Arizona. And in an answer that may further fuel the conspiracy fire, he added they are also operating in one Middle Eastern country; when I asked which one, he’d only say, “Can’t tell you.”

What we cannot do

The versions of weather modification that the conspiracy theorists envision most often—significantly altering monsoons or hurricanes or making the skies clear and sunny for weeks at a time—have so far proved impossible to carry out. But that’s not necessarily for lack of trying.

The US government attempted to alter a hurricane in 1947 as part of a program dubbed Project Cirrus. In collaboration with GE, government scientists seeded clouds with pellets of dry ice, the idea being that the falling pellets could induce supercooled liquid in the clouds to crystallize into ice. After they did this, the storm took a sharp left turn and struck the area around Savannah, Georgia. This was a significant moment for budding conspiracy theories, since a GE scientist who had been working with the government said he was “99% sure” the cyclone swerved because of their work. Other experts disagreed and showed that such storm trajectories are, in reality, perfectly possible without intervention. Perhaps unsurprisingly, public outrage and threats of lawsuits followed.

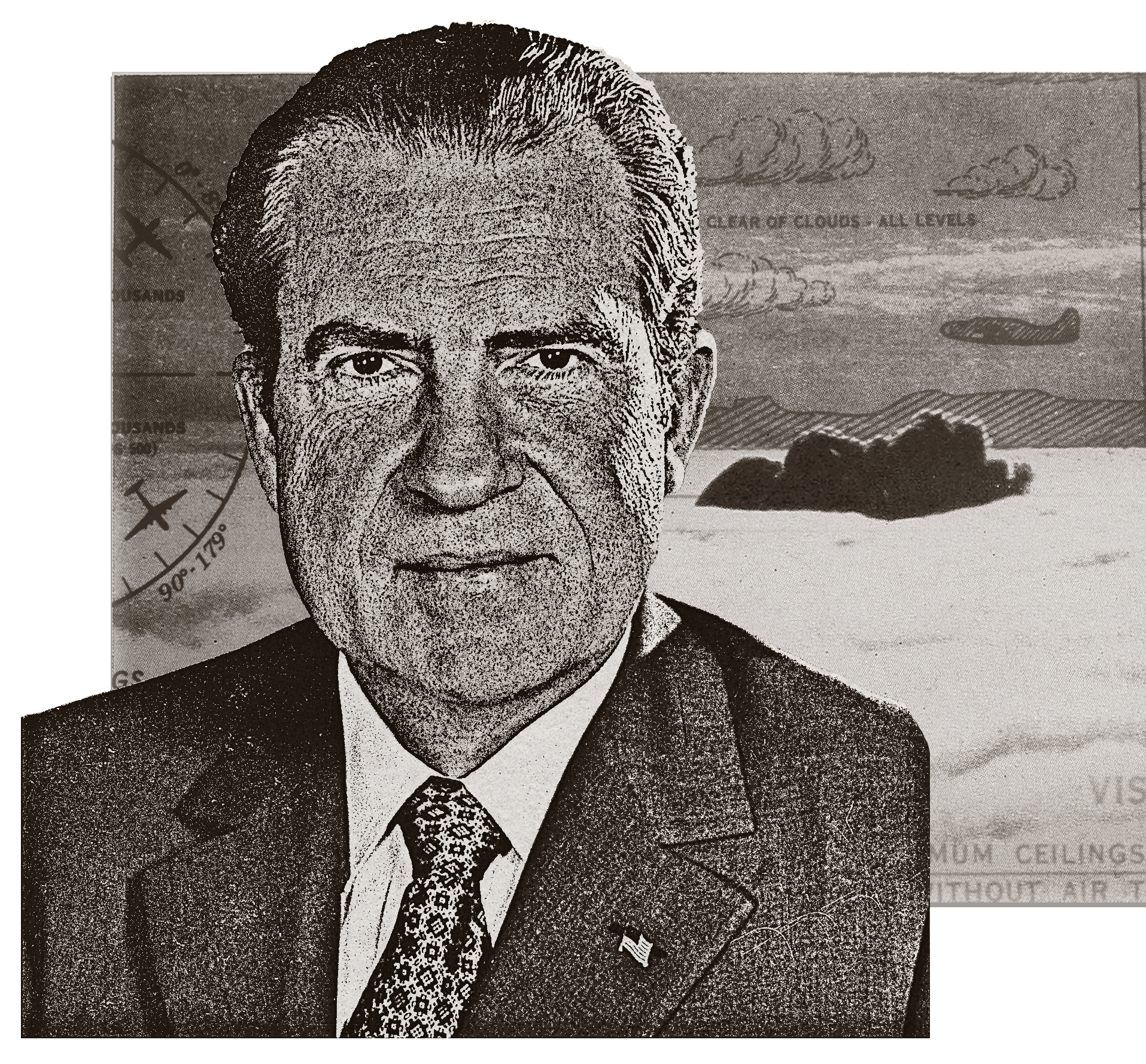

It took some time for the hubbub to die down, after which several US government agencies continued—unsuccessfully—trying to alter and weaken hurricanes with a long-running cloud seeding program called Project Stormfury. Around the same time, the US military joined the fray with Operation Popeye, essentially trying to harness weather as a weapon in the Vietnam War—engaging in cloud seeding efforts over Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos in the late 1960s and early 1970s, with an eye toward increasing monsoon rains and bogging down the enemy. Though it was never really clear whether these efforts worked, the Nixon administration tried to deny them, going so far as to lie to the public and even to congressional committees.

More recently and less menacingly, there have been experiments with Dyn-O-Gel—a Florida company’s super-absorbent powder, intended to be dropped into storm clouds to sop up their moisture. In the early 2000s, the company carried out experiments with the stuff in thunderstorms, and it had grand plans to use it to weaken tropical cyclones. But according to one former NOAA scientist, you would need to drop almost 38,000 tons of it, requiring nearly 380 individual plane trips, in and around even a relatively small cyclone’s eyewall to really affect the storm’s strength. And then you would have to do that again an hour and a half later, and so on. Reality tends to get in the way of the biggest weather modification ideas.

Beyond trying to control storms, there are some other potential weather modification technologies out there that are either just getting started or have never taken off. Swiss researchers have tried to use powerful lasers to induce cloud formation, for example; in Australia, where climate change is imperiling the Great Barrier Reef, artificial clouds created when ship-based nozzles spray moisture into the sky have been used to try to protect the vital ecosystem. In each case, the efforts remain small, localized, and not remotely close to achieving the kinds of control the conspiracy theorists allege.

What is not weather modification—but gets lumped in with it

Further worsening weather control conspiracies is that there is a tendency to conflate cloud seeding and other promising weather modification research with concepts such as chemtrails—a full-on conspiracist fever dream about innocuous condensation trails left by jets—and solar geoengineering, a theoretical stopgap to cool the planet that has been subject to much discussion and modeling research but has never been deployed in any large-scale way.

One controversial form of solar geoengineering, known as stratospheric aerosol injection, would involve having high-altitude jets drop tiny aerosol particles—sulfur dioxide, most likely—into the stratosphere to act essentially as tiny mirrors. They would reflect a small amount of sunlight back into space, leaving less energy to reach the ground and contribute to warming. To date, attempts to launch physical experiments in this space have been shouted down, and only tiny—though still controversial—commercial efforts have taken place.

One can see why it gets lumped in with cloud seeding: bits of stuff, dumped into the sky, with the aim of altering what happens down below. But the aims are entirely separate; geoengineering would alter the global average temperature rather than having measurable effects on momentary cloudbursts or hailstorms. Some research has suggested that the practice could alter monsoon patterns, a significant issue given their importance to much of the world’s agriculture, but it remains a fundamentally different practice from cloud seeding.

Still, the political conversation around supposed weather control often reflects this confusion. Greene, for instance, introduced a bill in July called the Clear Skies Act, which would ban all weather modification and geoengineering activities. (Greene’s congressional office did not respond to a request for comment.) And last year, Tennessee became the first state to enact a law to prohibit the “intentional injection, release, or dispersion, by any means, of chemicals, chemical compounds, substances, or apparatus … into the atmosphere with the express purpose of affecting temperature, weather, or the intensity of the sunlight.” Florida followed suit, with Governor Ron DeSantis signing SB 56 into law in June of this year for the same stated purpose.

Also this year, lawmakers in more than 20 other states have also proposed some version of a ban on weather modification, often lumping it in with geoengineering, even though caution on the latter is more widely accepted or endorsed. “It’s not a conspiracy theory,” one Pennsylvania lawmaker who cosponsored a similar bill told NBC News. “All you have to do is look up.”

Oddly enough, as Yeh of the University of Colorado points out, the places where bans have passed are states where weather modification isn’t really happening. “In a way, it’s easy for them to ban it, because, you know, nothing actually has to be done,” she says. In general, neither Florida nor Tennessee—nor any other part of the Southeast—needs any help finding rain. Basically, all weather modification activity in the US happens in the drier areas west of the Mississippi.

Finding a culprit

Doricko told me that in the wake of the Texas disaster, he has seen more people become willing to learn about the true capabilities of cloud seeding and move past the more sinister theories about it.

I asked him, though, about some of his company’s flashier branding: Until recently, visitors to the Rainmaker website were greeted right up top with the slogan “Making Earth Habitable.” Might this level of hype contribute to public misunderstanding or fear?

He said he is indeed aware that Earth is, currently, habitable, and called the slogan a “tongue-in-cheek, deliberately provocative statement.” Still, in contrast to the academics who seem more comfortable acknowledging weather modification’s limits, he has continued to tout its revolutionary potential. “If we don’t produce more water, then a lot of the Earth will become less habitable,” he said. “By producing more water via cloud seeding, we’re helping to conserve the ecosystems that do currently exist, that are at risk of collapse.”

While other experts cited that 10% figure as a likely upper limit of cloud seeding’s effectiveness, Doricko said they could eventually approach 20%, though that might be years away. “Is it literally magic? Like, can I snap my fingers and turn the Sahara green? No,” he said. “But can it help make a greener, verdant, and abundant world? Yeah, absolutely.”

It’s not all that hard to see why people still cling to magical thinking here. The changing climate is, after all, offering up what’s essentially weaponized weather, only with a much broader and long-term mechanism behind it. There is no single sinister agency or company with its finger on the trigger, though it can be tempting to look for one; rather, we just have an atmosphere capable of holding more moisture and dropping it onto ill-prepared communities, and many of the people in power are doing little to mitigate the impacts.

“Governments are not doing a good job of responding to the climate crisis; they are often captured by fossil-fuel interests, which drive policy, and they can be slow and ineffective when responding to disasters,” Naomi Smith, a lecturer in sociology at the University of the Sunshine Coast in Australia who has written about conspiracy theories and weather events, writes in an email. “It’s hard to hold all this complexity, and conspiracy theorizing is one way of making it intelligible and understandable.”

“Conspiracy theories give us a ‘big bad’ to point the finger at, someone to blame and a place to put our feelings of anger, despair, and grief,” she writes. “It’s much less satisfying to yell at the weather, or to engage in the sustained collective action we actually need to tackle climate change.”

The sinister “they” in Greene’s accusations is, in other words, a far easier target than the real culprit.

Dave Levitan is an independent journalist, focused on science, politics, and policy. Find his work at davelevitan.com and subscribe to his newsletter at gravityisgone.com.