Colossus: The Prototype

For much of the past year, xAI’s infrastructure story did not unfold across a portfolio of sites. It unfolded inside a single building in Memphis, where the company first tested what an “AI factory” actually looks like in physical form. That building had a name that matched the ambition: Colossus.

The Memphis-area facility, carved out of a vacant Electrolux factory, became shorthand for a new kind of AI build: fast, dense, liquid-cooled, and powered on a schedule that often ran ahead of the grid. It was an “AI factory” in the literal sense: not a cathedral of architecture, but a machine for turning electricity into tokens.

Colossus began as an exercise in speed. xAI took over a dormant industrial building in Southwest Memphis and turned it into an AI training plant in months, not years. The company has said the first major system was built in about 122 days, and then doubled in roughly 92 more, reaching around 200,000 GPUs.

Those numbers matter less for their bravado than for what they reveal about method. Colossus was never meant to be bespoke. It was meant to be repeatable. High-density GPU servers, liquid cooling at the rack, integrated CDUs, and large-scale Ethernet networking formed a standardized building block. The rack, not the room, became the unit of design.

Liquid cooling was not treated as a novelty. It was treated as a prerequisite. By pushing heat removal down to the rack, xAI avoided having to reinvent the data hall every time density rose. The building became a container; the rack became the machine.

That design logic, e.g. industrial shell plus standardized AI rack, has quietly become the template for everything that followed.

Power: Where Speed Met Reality

What slowed the story was not compute, cooling, or networking. It was power.

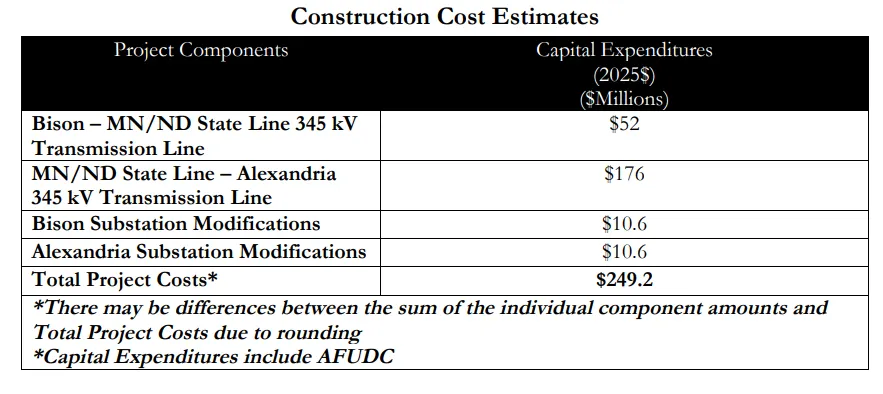

TVA and Memphis Light, Gas & Water approved an initial 150 megawatts of grid service for Colossus, with a second 150-megawatt increment planned to bring the campus to 300 MW. Delivery was staged. Early power came partly from an existing substation and partly from a new one. Another new substation and further upgrades were required to reach the second 150 MW. xAI also accepted curtailment provisions that allow the utility to reduce its load during periods of grid stress.

That is now a familiar pattern in AI development: power arrives in chapters, not in a single finished volume.

To keep its compute schedule intact while grid work caught up, xAI turned to interim natural-gas generation on site. What was meant to be temporary quickly became central to the project’s public identity. Environmental and civil-rights groups challenged the generators under the Clean Air Act. Permits were issued for some units, contested for others. Some equipment was removed as substations came online. Community opposition, especially in nearby predominantly Black neighborhoods, intensified.

From an infrastructure perspective, Memphis exposed a widening gap. AI deployment now runs on startup timelines. Grid infrastructure still runs on utility timelines. The space between them is filled with “temporary” solutions that are anything but politically invisible.

Water Joins Power as a Constraint

Water entered the picture as well. As part of its negotiations in Memphis, xAI proposed funding a recycled wastewater plant capable of supplying up to 13 million gallons per day of treated water, reducing reliance on local aquifers. The idea was to decouple cooling growth from freshwater draw, using municipal discharge as an industrial input rather than a waste stream.

It was an unusual move. Not because recycled water is exotic, but because it was positioned as part of the core strategy, not a side mitigation. In the AI era, water is joining power as a first-order constraint.

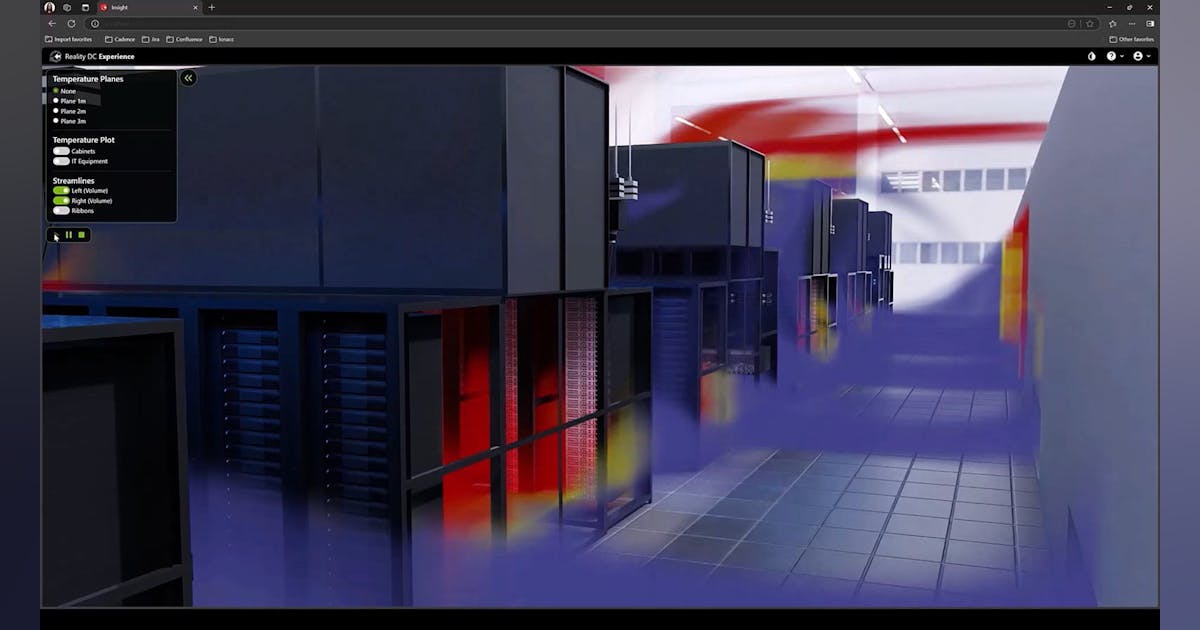

Across the data center sector, that shift is already visible. Hyperscalers and large operators are increasingly designing around three parallel questions: where does the power come from, how fast can it arrive, and what happens to water when density doubles or triples. In arid and semi-arid markets, that has pushed operators toward reclaimed water, air-assisted or hybrid cooling, and explicit “water-positive” pledges tied to local replenishment projects. In wetter regions, it has meant negotiating priority access, investing in treatment infrastructure, or redesigning cooling systems to reduce make-up water per megawatt.

What makes xAI’s approach notable is not that it recognized the problem, but that it treated water infrastructure the same way it treated power: as something that might need to be built, financed, and integrated directly into the project, rather than assumed to be available. The recycled-water proposal effectively reframed cooling as a civic-scale utility problem, not just a facilities-engineering problem.

That framing is likely to spread. As AI racks push thermal density higher, cooling systems are no longer a quiet background function. They are becoming visible parts of local resource politics; just like substations, transmission lines, and backup generation. In that sense, xAI’s wastewater proposal is less an outlier than a preview: in the next phase of the AI data center cycle, successful projects will not just secure megawatts. They will have to secure gallons, too.