“Our ten-year outlook is now compressed into three.”

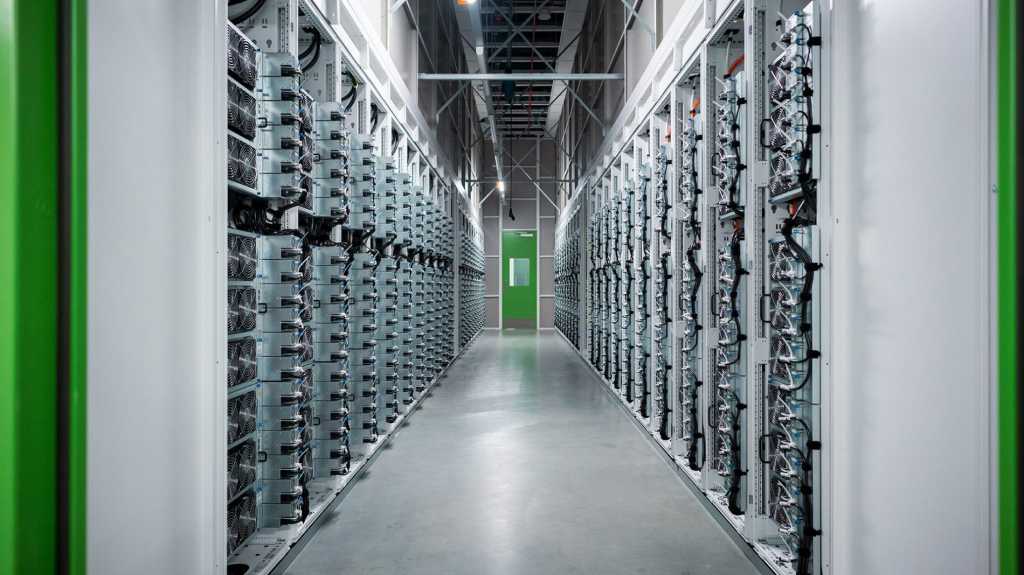

Every utility planner I talk to has their own version of this line. The surge in demand from data centers, AI, and electrification has everyone’s attention. But the real challenge is how quickly customers now need to be connected. The grid was built for steady, predictable growth, but AI is delivering growth on timelines the system has never seen.

Transmission lines still take seven to ten years to permit and build. Substation expansions run across multiple planning cycles. Large power transformers routinely have two-year delivery times. Meanwhile, new data centers and industrial loads expect to be energized in eighteen to thirty-six months.

Here’s what that looks like in practice: A high-growth corridor might get 500 MW of new data center requests over 24 months. The nearest 230 or 345 kV upgrade is six to eight years out. The utility might have generation capacity on the broader system, but not the local infrastructure to move or stabilize that power in time. For customers aiming to connect in 2026, the upgrades they technically require might not arrive until early next decade.

Across the country, the scale of what’s trying to connect is dramatically bigger than what already exists. The U.S. has about 1,189 gigawatts of utility-scale generation operating today. But more than 1,350 gigawatts of new generation and hundreds of gigawatts of storage sit in interconnection queues. Even if only a fraction is built, it shows how fast the system has to grow.

And behind the capacity crunch is the stability challenge.

For decades, large rotating generators didn’t just produce energy. The inertia in those large spinning turbines absorbed disturbances. Their voltage control held the system steady. These characteristics acted as shock absorbers for the grid, and planners could assume they were always present. As those units retire, stability becomes a local requirement, especially in regions where large, fast-growing loads cluster quickly. Stability used to be a passive byproduct of large power plants, but now it has to be intentionally designed in.

So utilities are being pushed toward solutions that fit the timelines they’re facing right now, not the timelines they had ten years ago.

Three requirements are emerging as central: speed, stability, and location.

Infrastructure has to be deployable on timelines that match new loads. It has to deliver grid-forming characteristics once provided by synchronous machines. And it has to sit close to the point of consumption, where fast-growing demand actually lives.

Traditional tools struggle under these constraints. That’s why many utilities are now evaluating modular units, including flexible thermal capacity, hybrid systems, advanced grid-forming storage, distributed resources, or microgrid building blocks. These systems can be placed near load centers and brought online much faster than large infrastructure. They give planners the ability to reinforce fast-growing pockets of the grid without locking in unnecessary long-term cost.

Fast, flexible assets can defer or reduce major capital projects. That breathing room allows long-lead upgrades, especially transmission, to move forward in an orderly, right-sized way instead of being rushed or oversized.

Partnerships are also accelerating. Across the country, utilities and large commercial or industrial customers are co-investing in infrastructure near growth corridors. The logic is simple: the entities driving the load help support the solution, while residential and small-business customers are protected.

And utilities are placing more value on what they prevent: outages, curtailments, bottlenecks, and delays. When avoided costs are fully considered, fast-to-deploy assets become essential to maintaining affordability.

We need a grid architecture built for variable timelines and uneven growth.

What this moment requires from utilities is a shift in tempo: faster evaluation cycles for flexible load solutions; parallel planning that allows transmission to move forward while fast-deploying assets bridge the gap; and cost-sharing frameworks that make sure high-growth customers participate in strengthening the grid.

The demand is here, and it’s not slowing down. The utilities that stay ahead will be the ones who solve the challenge of moving faster. They’ll be the ones who adjust the planning tempo, redesign system assumptions, and embrace tools that match the pace of modern load growth.

If we get this right, we’ll have a grid that’s stronger, more resilient, and better aligned with how energy is produced and consumed today.