After months of uncertainty in 2024, momentum is starting to build in the North Sea’s energy transition in 2025, according to the head of Aquaterra Energy.

Throughout 2024, the UK’s offshore oil and gas sector sounded the alarm over Labour’s plans to increase the windfall tax and cut investment allowances.

The sector criticised the decision to increase the Energy Profits Levy (EPL) in last year’s October budget, warning it would “hasten the demise” of the industry and put jobs and energy transition targets at risk.

But speaking to Energy Voice, Aquaterra chief executive George Morrison said the UK has seen a “quite positive” start to 2025 with several final investment decisions (FIDs).

“Beyond just the North Sea, but generally industrially, we’re seeing an awful lot of FIDs that seem to have been delayed for quite some time actually finally getting made,” Morrison said.

“A lot of those FIDs are for North Sea projects, and we’re very glad to see it.

“People are starting to move ahead with some of the big projects that are essential to the sector’s future.”

Morrison said a key area which is beginning to see movement is carbon capture and storage (CCS).

The UK government and Italian operator Eni reached a financial agreement for the Liverpool Bay CCS project, part of the HyNet North West industrial cluster.

© Supplied by px Group

© Supplied by px GroupIt came after North Sea operators BP, Equinor and TotalEnergies secured approval in December for their £4 billion Northern Endurance Partnership (NEP) in Teesside.

With major CCS projects across the UK starting to take shape, Morrison said “momentum has been building for a long period of time” in the North Sea’s energy transition.

“An awful lot of planning and preparation has been done,” he said.

“I’m hopeful that what we’ve actually seen is the start of a tipping point from planning to action, particularly in the CCS space.”

Aquaterra sees ‘steady growth’ in CCS projects

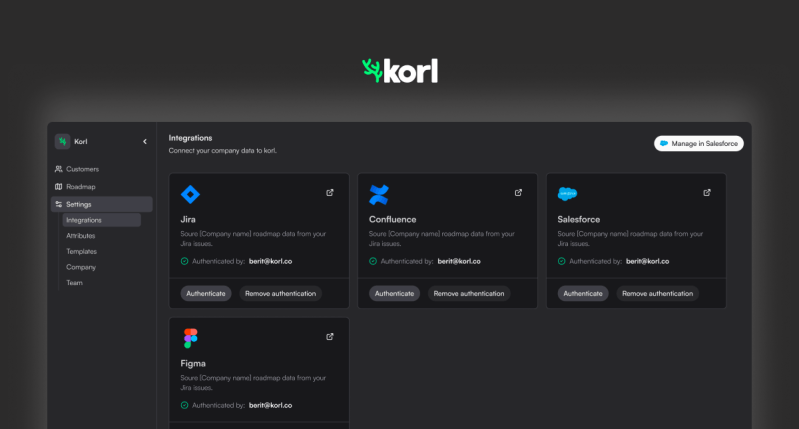

In recent years, Morrison said Aquaterra has worked in the planning stages of large offshore CCS projects.

This has given Aquaterra the opportunity to develop techniques and intellectual property in the nascent sector.

Morrison said the CCS industry has now moved to a point where Aquaterra is seeing its engineering translate into orders for “physical kit”.

“We’ve seen a steady growth in CCS project orders from a very low base,” he said.

“This year so far, CCS has made up over 20% of our order intake for the year, which is hugely encouraging.

© Supplied by Aquaterra Energy

© Supplied by Aquaterra Energy“That’s the sort of scale that we need to see projects start to come along.”

While the EPL is continuing to impact the offshore oil and gas sector and Aberdeen’s wider economy, Morrison said the UK remains “extremely well placed” in CCS.

“We’re an international company that’s always worked in the oil industry and we’ve always talked about the fact that we’ve worked in 60 countries and six continents and oil and gas,” he said.

“We’re currently working in, I think, six countries and three continents in CCS. The UK definitely is a keystone of that market.”

But Morrison warned CCS is “advancing at pace globally rather than just domestically”, and said the UK needs to focus on developing its expertise to stay ahead.

“The fact that UK projects are moving ahead is great and very pleasing and gives us a chance to do things,” he said.

“What’s most important is whether or not the UK is able to build a knowledge-based economy in that sector beyond UK projects, and that I think is moving ahead.

“The government can certainly encourage developments in the UK, but the more important thing is for the private sector to be developing the IP that builds a long-term future for us.”

UK’s ‘entrepreneurial spirit’ an energy transition advantage

While CCS projects in Denmark and Norway are moving ahead, Morrison said an advantage for the UK is its “better track record” at developing and exporting solutions within the oil and gas sector.

“I’m hoping that entrepreneurial spirit still exists in the UK, and (Aquaterra) won’t be the only ones that have taken the time to prepare and build a really strong foundation,” he said.

“We’ve got to bear in mind that we’re competing internationally and we shouldn’t be entirely focused just on the domestic scene.”

While major UK CCS projects in the Track-1 process are moving ahead, uncertainty remains around Track-2 projects such as Acorn in Scotland and Viking in the Humber.

© Supplied by Shell

© Supplied by ShellBut although Morrison wants to see Acorn go ahead “earlier than later”, he said Aquaterra is currently tracking about as many CCS projects globally as it is within oil and gas.

“We need to be thinking about the UK as perhaps a proving ground, a place where you can hone your skills,” he said.

“If UK companies only participate in and benefit from UK-based projects, [that] is not the model that we should follow for building a long-term value proposition for the UK.

“In oil and gas, we were very good at developing things in the UK and then taking them and using them around the world… I think you need to do the same thing in CCS.”

Floating wind and green hydrogen

Alongside CCS, Morrison said Aquaterra is also pursuing growth in other emerging energy transition sectors such as floating wind and green hydrogen.

But these “extremely different industries” all come with their own challenges, he said, and are developing at a different pace.

“We often seem to talk about the energy transition as one thing and one sector, but it really isn’t,” he said.

“It’s almost like lumping oil and gas, and coal together.”

In a similar vein, Morrison said the UK needs to start viewing wind energy as an extractive industry – less ‘wind farm’ and more ‘wind mine’ or ‘wind well’.

© Supplied by Flotation Energy

© Supplied by Flotation EnergyWhile the UK has so far done a “very good job” of exploiting those wind resources through fixed-bottom wind, Morrison said the country has struggled to develop that resource into long-term societal and industrial benefits.

“When we were putting in lots of coal mines, we were building lots of jobs around those that you’re enabling the industrial revolution that made everyone get more wealthy,” he said.

“I don’t think so far anyone’s felt like the wind industry and exploiting it in the UK has made any of us more wealthy, and it hasn’t built communities.”

In floating wind and green hydrogen, Morrison sees an opportunity for the UK to extract far greater value from its wind resources.

“That seems like the way to take that extractive industry, where you’re generating a primary product in terms of electricity and add value to that electricity and turn it into something that’s widely exportable, produces lots of jobs, and produces something that actually is useful beyond just the extraction of the resource itself,” he said.

“If all we’re producing is electricity from it, and that electricity is being produced and fed into other country’s industrial benefit, then we’re in the resource trap.”

North Sea offshore green hydrogen

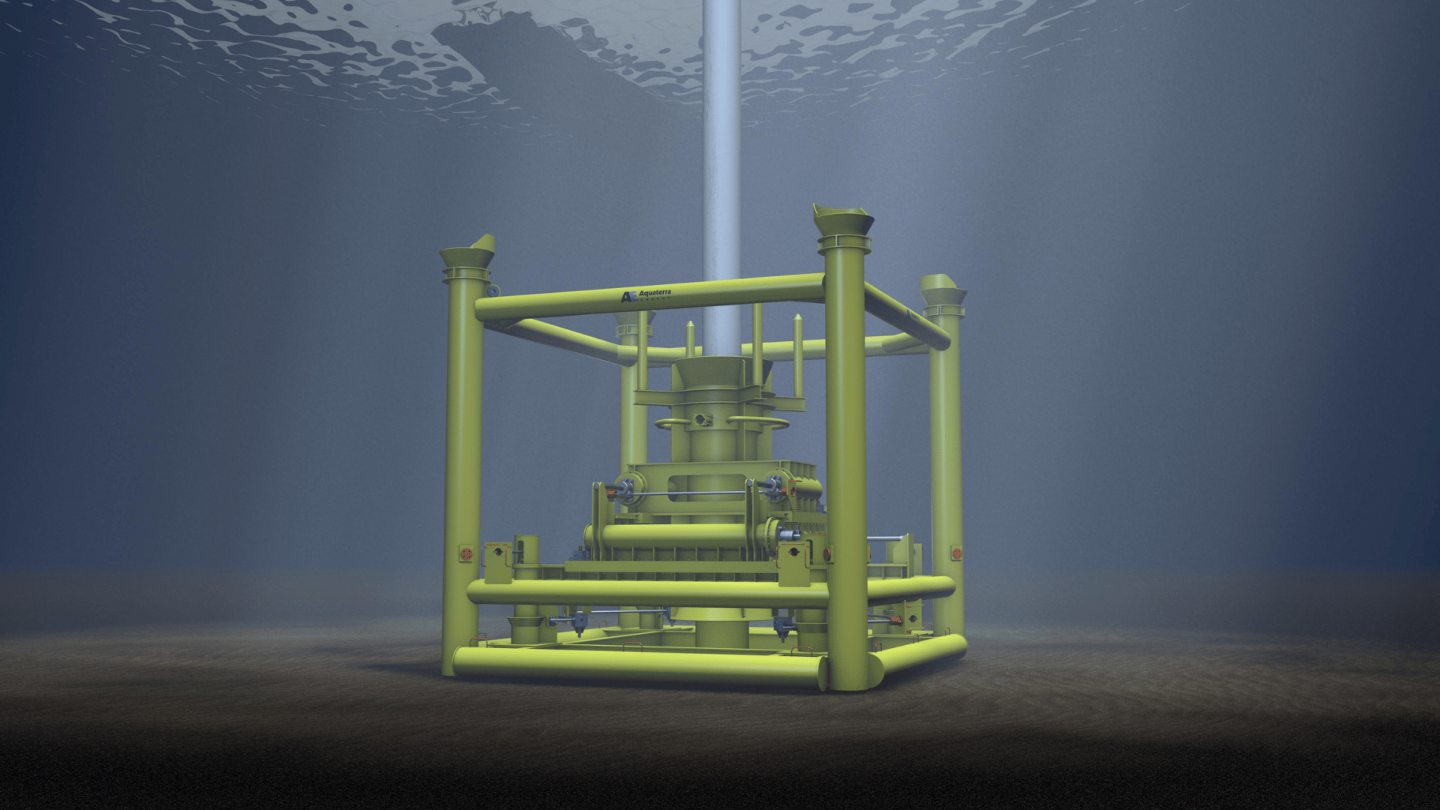

While Aquaterra sees CCS as its primary focus at present, in the longer term Morrison views offshore green hydrogen as a future growth opportunity for the company.

“It’s a bit like the link between coal mining and steel back in the early days of the industrial revolution in that you produce steel close to where you get the coal,” he said.

“I think the hydrogen market will be very much like that… producing hydrogen close to source is going to be the key to that market.”

With the UK benefiting from its geography and existing skills and expertise, Morrison said offshore green hydrogen “should be a very big part of the UK’s energy mix into the 2030s”.

“That will be the next big thing potentially for us to become very relevant in and make a marked difference to our business,” he said.

‘Rich and green, not poor and green’

Overall, Morrison said the UK is “making steady progress” in its clean energy mission.

But he wants to see the UK’s offshore wind sector “delivering societal benefits rather than benefiting from societal support”.

“We generate about as much of our electricity now from offshore wind as we used to generate from coal, but we haven’t generated the same societal benefit,” he said.

“We still produce some of the best mining engineers in the world, and send them all over the world, based on things that we were doing a century ago in that type of industry.

“That’s the key focus for me in this energy transition, that what we want to achieve is to become rich and green, not poor and green.”