Inside Chicago’s surveillance panopticon

Early on the morning of September 2, 2024, a Chicago Transit Authority Blue Line train was the scene of a random and horrific mass shooting. Four people were shot and killed on a westbound train as it approached the suburb of Forest Park. The police swiftly activated a digital dragnet—a surveillance network that connects thousands of cameras in the city. The process began with a quick review of the transit agency’s surveillance cameras, which captured the alleged gunman shooting the victims execution style. Law enforcement followed the suspect, through real-time footage, across the rapid-transit system. Police officials circulated the images to transit staff and to thousands of officers. An officer in the adjacent suburb of Riverdale recognized the suspect from a previous arrest. By the time he was captured at another train station, just 90 minutes after the shooting, authorities already had his name, address, and previous arrest history. Little of this process would come as much surprise to Chicagoans. The city has tens of thousands of surveillance cameras—up to 45,000, by some estimates. That’s among the highest numbers per capita in the US. Chicago boasts one of the largest license plate reader systems in the country, and the ability to access audio and video surveillance from independent agencies such as the Chicago Public Schools, the Chicago Park District, and the public transportation system as well as many residential and commercial security systems such as Ring doorbell cameras. Law enforcement and security advocates say this vast monitoring system protects public safety and works well. But activists and many residents say it’s a surveillance panopticon that creates a chilling effect on behavior and violates guarantees of privacy and free speech. Black and Latino communities in Chicago have historically been targeted by excessive policing and surveillance, says Lance Williams, a scholar of urban violence at Northeastern Illinois University. That scrutiny has created new problems without delivering the promised safety, he suggests. In order to “solve the problem of crime or violence and make these communities safer,” he says, “you have to deal with structural problems,” such as the shortage of livable-wage jobs, affordable housing, and mental-health services across the city.

Recent years have seen some effective pushback against the surveillance. Until recently, for example, the city was the largest customer of ShotSpotter acoustic sensors, which are designed to detect gunfire and alert police. The system was introduced in a small area on the South Side in 2012. By 2018, an area of about 136 square miles—some 60% of the city—was covered by the acoustic surveillance network. Critics questioned ShotSpotter’s effectiveness and objected that the sensors were installed largely in Black and Latino neighborhoods. Those critiques gained urgency with the fatal shooting in March 2021 of a 13-year-old, Adam Toledo, by police responding to a ShotSpotter alert. The tragedy became the touchstone of the #StopShotSpotter protest movement and one of the major issues in Brandon Johnson’s successful mayoral campaign in 2023. When he reached office, Johnson followed through, ending the city’s contract with SoundThinking, the San Francisco Bay Area company behind ShotSpotter. In total, it’s estimated the city paid more than $53 million for the system.

In response to a request for comment, SoundThinking said that ShotSpotter enables law enforcement “to reach the scene faster, render aid to victims, and locate evidence more effectively.” It stated the company “plays no part in the selection of deployment areas” but added: “We believe communities experiencing the highest levels of gun violence deserve the same rapid emergency response as any other neighborhood.” While there has been successful resistance to police surveillance in the nation’s third-largest city, there are also countervailing forces: governments and officials in Chicago and the surrounding suburbs are moving to expand the use of surveillance, also in response to public pressure. Even the victory against acoustic surveillance might be short-lived. Early last year, the city issued a request for proposals for gun violence detection technology. Many people in and around Chicago—digital privacy and surveillance activists, defense attorneys, law enforcement officials, and ordinary citizens—are part of this push and pull. Here are some of their stories. Alejandro Ruizesparza and Freddy MartinezCofounders, Lucy Parsons Labs Oak Park, a quiet suburb at Chicago’s western border, is the birthplace of Ernest Hemingway. It includes the world’s largest collection of Frank Lloyd Wright–designed buildings and homes. Until recently, the village of Oak Park was also the center of a three-year-long campaign against an unwelcome addition to its manicured lawns and Prairie-style architecture: automated license plate readers from a company called Flock Safety. These are high-speed cameras that automatically scan license plates to look for stolen or wanted vehicles, or for drivers with outstanding warrants. Freddy Martinez (left) and Alejandro Ruizesparza (right) direct Lucy Parsons Labs, a charitable organization focused on digital rights.AKILAH TOWNSEND An Oak Park group called Freedom to Thrive—made up of parents, activists, lawyers, data scientists, and many others—suspected that this technology was not a good or equitable addition to their neighborhood. So the group engaged the Chicago-based nonprofit Lucy Parsons Labs to help navigate the often intimidating process of requesting license plate reader data under the Illinois Freedom of Information Act. Lucy Parsons Labs, which is named for a turn-of-the-century Chicago labor organizer, investigates technologies such as license plate readers, gunshot detection systems, and police bodycams. LPL provides digital security and public records training to a variety of groups and is frequently called on to help community members audit and analyze surveillance systems that are targeting their neighborhoods. It’s led by two first-generation Mexican-Americans from the city’s Southwest Side. Alejandro Ruizesparza has a background in community organizing and data science. Freddy Martinez was also a community organizer and has a background in physics.

The group is now approaching its 10th year, but it was an all-volunteer effort until 2022. That’s when LPL received its first unrestricted, multi-year operational grant from a large foundation: the Chicago-based John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, known worldwide for its so-called “genius grants.” A grant from the Ford Foundation followed the next year. The additional resources—a significant amount compared with the previous all-volunteer budget, acknowledges Ruizesparza—meant the two cofounders and two volunteers became full-time employees. But the group is determined not to become “too comfortable” and lose its edge. There is a tenacity to Lucy Parsons Labs’ work—a “sense of scrappiness,” they say—because “we did so much of this work with no money.” One of LPL’s primary strategies is filing extensive FOIA requests for raw data sets of police surveillance. The process can take a while, but it often reveals issues. In the case of Oak Park, the FOIA requests were just one tool that Freedom to Thrive and LPL used to sort out what was going on. The data revealed that in the first 10 months of operation, the eight Flock license plate readers the town had deployed scanned 3,000,000 plates. But only 42 scans led to an alert—an infinitesimal yield of 0.000014%.

At the same time, the impacts of those few flagged license plates were disproportionate. While Oak Park’s population of about 53,000 is only 19% Black, Black drivers made up 85% of those flagged by the Flock cameras, seemingly amplifying what were already concerning racial disparities in the village’s traffic stops. Flock did not respond to a request for comment. “We became almost de facto experts in navigating the process and the law. I think that sort of speaks to some of the DIY punk aesthetic.” Freddy Martinez, cofounder, Lucy Parsons Labs LPL brings a mix of radical politics and critical theory to its mission. Most surveillance technologies are “largely extensions of the plantation systems,” says Ruizesparza. The comparison makes sense: Many slaveholding communities required enslaved persons to carry signed documents to leave plantations and wear badges with numbers sewn to their clothing. The group says it aims to empower local communities to push back against biased policing technologies through technical assistance, training, and litigation—and to demystify algorithms and surveillance tools in the process. “When we talk to people, they realize that you don’t need to know how to run a regression to understand that a technology has negative implications on your life,” says Ruizesparza. “You don’t need to understand how circuits work to understand that you probably shouldn’t have all of these cameras embedded in only Black and brown regions of a city.”

The group came by some of its techniques through experimentation. “When LPL was first getting started, we didn’t really feel like FOIA would have been a good way of getting information. We didn’t know anything about it,” says Martinez. “Along the way, we were very successful in uncovering a lot of surveillance practices.” One of the covert surveillance practices uncovered by those aggressive FOIA requests, for example, was the Chicago Police Department’s use of “Stingray” equipment, portable surveillance devices deployed to track and monitor mobile phones. The contentious issue of Oak Park’s license plate readers was finally put to a vote in late August. The village trustees voted 5–2 to terminate the contract with Flock Safety. Since then, community-based groups from across the country—as far away as California—have contacted LPL to say the Chicago collective’s work has inspired their own efforts, says Martinez: “We became almost de facto experts in navigating the process and the law. I think that sort of speaks to some of the DIY punk aesthetic.” Brian Strockis Chief, Oak Brook Police Department If you drive about 20 miles west of Chicago, you’ll find Oakbrook Center, one of the nation’s leading luxury shopping destinations. The open-air mall includes Neiman-Marcus, Louis Vuitton, and Gucci and attracts high-end shoppers from across the region. It’s also become a destination for retail theft crews that coordinate “smash and grabs” and often escape with thousands of dollars’ worth of inventory that can be quickly sold, such as sunglasses or luxury handbags. In early December, police say, a Chicago man tried to lead officers on what could have been a dangerous high-speed chase from the mall. Patrol cars raced to the scene. So did a “first responder drone,” built by Flock Safety and deployed by the Oak Brook Police Department. The drone identified the suspect vehicle from the mall parking lot using its license plate reader and snapped high-definition photos that were texted to officers on the ground. The suspect was later tracked to Chicago, where he was arrested. Brian Strockis, chief of the Oak Brook Police Department, led the way in introducing drones as first responders in the state of Illinois.AKILAH TOWNSEND This was the type of outcome that Brian Strockis, chief of the Oak Brook Police Department, hoped for when he pioneered the “drone as first responder,” or DFR, program in Illinois. A longtime member of the force, he joined the department almost 25 years ago as a patrol officer, worked his way up the brass ladder, and was awarded the top job in 2022.

Oak Brook was the first municipality in Illinois to deploy a drone as a first responder. One of the main reasons, says Strockis, was to reduce the number of high-speed chases, which are potentially dangerous to officers, suspects, and civilians. A drone is also a more effective and cost-efficient way to deal with suspects in fleeing vehicles, says Strockis. Police say there was the potential for a dangerous high-speed chase. Patrol cars raced to the scene. But the first unit to arrive was a drone. “It’s a force multiplier in that we’re able to do more with less,” says the chief, who spoke with me in his office at Oak Brook’s Village Hall.

The department’s drone autonomously launches from the roof of the building and responds to about 10 to 12 service calls per day, at speeds up to 45 miles per hour. It arrives at crime scenes before patrol officers in nine out of every 10 cases. Next door to Village Hall is the Oak Brook Police Department’s real-time crime center, a large room with two video walls that integrates livestreams from the first-responder drone, handheld drones, traffic cameras, license plate readers, and about a thousand private security cameras. When I visited, the two DFR operators demonstrated how the machine can fly itself or be directed to locations from a destination entered on Google Maps. They sent it off to a nearby forest preserve and then directed it to return to the rooftop base, where it docks automatically, changes batteries, and charges. After the demo, one of the drone operators logged the flight, as required by state law. Strockis says he is aware of the privacy concerns around using this technology but that protections are in place. For example, the drone cannot be used for random or mass surveillance, he says, because the camera is always pointed straight ahead during flight and does not angle down until it reaches its desired location. The drone’s payload does not include facial recognition technology, which is restricted by state law, he says. The drone video footage is invaluable, he adds, because “you are seeing the events as they’re transpiring from an angle that you wouldn’t otherwise be privy to.” It’s an extra layer of protection for the public as well as for the officers, says the chief: “For every incident that an officer responds to now, you have squad car and bodycam video. You likely have cell-phone video from the public, officers, complainants, from offenders. So adding this element is probably the best video source on a scene that the police are going to anyway.” Mark Wallace Executive director, Citizens to Abolish Red Light Cameras Mark Wallace wears several hats. By day he is a real estate investor and mortgage lender. But he is probably best known to many Chicagoans—especially across the city’s largely African-American communities on the South and West Sides—as a talk radio host for the station WVON and one of the leading voices against the city’s extensive network of red-light and speed cameras. For the past two decades, city officials have maintained that the cameras—which are officially known as “automated enforcement”—are a crucial safety measure. They are also a substantial revenue stream, generating around $150 million a year and a total of some $2.5 billion since they were installed.

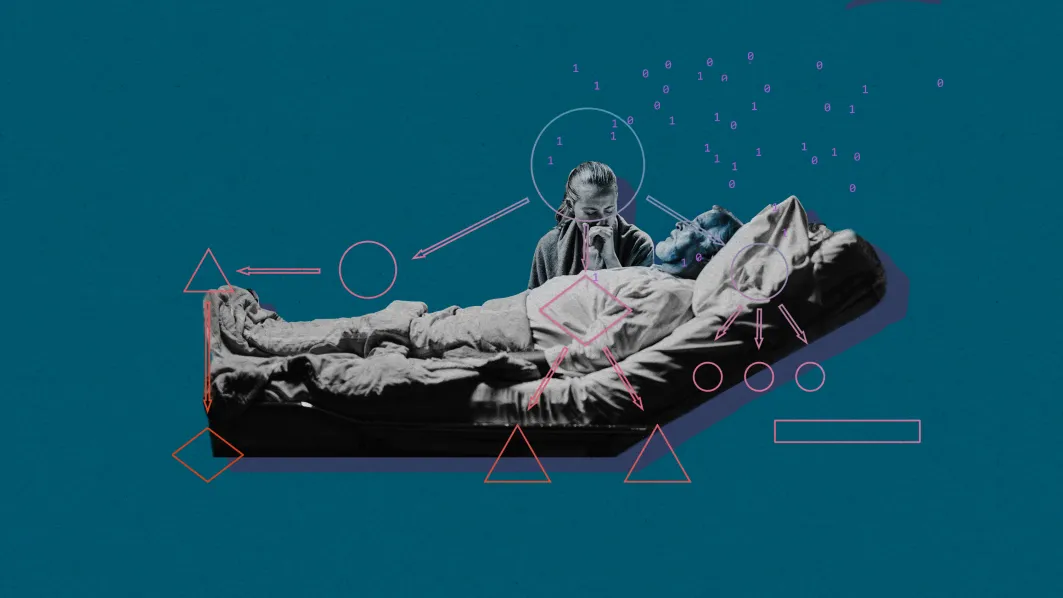

Urged on by a radio listener, Mark Wallace started organizing against Chicago’s red-light and speed cameras, a substantial revenue stream for the city that has been found to disproportionately burden majority Black and Latino areas.AKILAH TOWNSEND “The one thing that the cameras have the ability to do is generate a lot of money,” Wallace says. He describes the tickets as a “cash grab” that disproportionately affects Black and Latino communities. A groundbreaking 2022 analysis by ProPublica found, in fact, that households in majority Black and Latino zip codes were ticketed at much higher rates than others, in part because the cameras in those areas were more likely to be installed near expressway ramps and on wider streets, which encouraged faster speeds. The tickets, which can quickly rack up late fees, were also found to cause more of a financial burden in such communities, the report found. These were some of the same concerns that many people expressed on the radio and in meetings, Wallace says. Chicago’s automated traffic enforcement began in 2003, and it became the most extensive—and most lucrative—such program in the country. About 300 red-light cameras and 200 speed cameras are set up near schools and parks. The cost of the tickets can quickly double if they are not paid or contested—providing a windfall for the city. Wallace began his advocacy against the cameras soon after arriving at the radio station in the early 2010s. A younger listener called in and said, he recalls, “that he enjoyed the information that came from WVON but that we didn’t do anything.” The comment stuck with him, especially in light of WVON’s storied history. The station was closely involved in the civil rights movement of the 1960s and broadcast Martin Luther King Jr.’s speeches during his Chicago campaign. Wallace hoped to change the caller’s perception about the station. He had firsthand experience with red-light cameras, having been ticketed himself, and decided to take them on as a cause. He scheduled a meeting at his church for a Friday night, promoting it on his show. “More than 300 people showed up,” he remembers, chatting with me in the spacious project studio and office in the basement of his townhouse on the city’s South Side. “That said to me there are a lot of people who see this inequity and injustice.” Wallace began using his platform on WVON—The People’s Show—to mobilize communities around social and economic justice, and many discussions revolved around the automated enforcement program. The cause gained traction after city and state officials were found to have taken thousands of dollars from technology and surveillance companies to make sure their cameras remained on the streets. Wallace and his group, Citizens to Abolish Red Light Cameras, want to repeal the ordinances authorizing the city’s camera programs. That hasn’t happened so far, but political pressure from the group paved the way for a Chicago City Council ordinance that required public meetings before any red-light cameras are installed, removed, or relocated. The group hopes for more restrictions for speed cameras, too. “It was never about me personally. It was about ensuring that we could demonstrate to people that you have power,” says Wallace. “If you don’t like something, as Barack Obama would say, get a pen and clipboard and go to work to fight to make these changes.” Jonathan Manes Senior counsel, MacArthur Justice Center Derick Scruggs, a 30-year-old father and licensed armed security guard, was working in the parking lot of an AutoZone on Chicago’s Southwest Side on April 19, 2021. That’s when he was detained, interrogated, and subjected to a “humiliating body search” by two Chicago police officers, Scruggs later attested. “I was just doing my job when police officers came at me, handcuffed me, and treated me like a criminal—just because I was near a ShotSpotter alert,” he says. The officers found no evidence of a shooting and released Scruggs. But the next day, the police returned and arrested him for an alleged violation related to his security guard paperwork. Prosecutors later dismissed the charges, but he was held in custody overnight and was then fired from his job. “Because of what they did,” he says, “I lost my job, couldn’t work for months, and got evicted from my apartment.” Jonathan Manes litigated cases related to detentions at Guantanamo Bay and the legality of drone strikes before turning his attention to Chicago’s implementation of gunshot detection technology.AKILAH TOWNSEND Scruggs is believed to be among thousands of Chicagoans who’ve been questioned, detained, or arrested by police because they were near the location of a ShotSpotter alert, according to an analysis by the City of Chicago Office of Inspector General. The case caught the attention of Jonathan Manes, a law professor at Northwestern and senior counsel at the MacArthur Justice Center, a public interest law firm. Manes previously worked in national security law, but when he joined the justice center about six years ago, he chose to focus squarely on the intersection of civil rights with police surveillance and technology. “My goal was to identify areas that weren’t well covered by other civil rights organizations but were a concern for people here in Chicago,” he says. “There is a need for much broader structural change to how the city chooses to use surveillance technology and then deploys it.” Jonathan Manes, senior counsel, MacArthur Justice Center And when he and his colleagues looked into ShotSpotter, they revealed a disturbing problem: The system generated alerts that yielded no evidence of gun-related crimes but were used by police as a pretext for other actions. There seemed to be “a pattern of people being stopped, detained, questioned, sometimes arrested, in response to a ShotSpotter alert—often resulting in charges that have nothing to do with guns,” Manes says. The system also directed a “massive number of police deployments onto the South and West Sides of the city,” Manes says. Those regions are home to most of Chicago’s Black and Latino residents. The research showed that 80% of the city’s Black population but only 30% of its white population lived in districts covered by the system. Manes brought Scruggs’s case into a lawsuit that he was already developing against the city’s use of ShotSpotter. In late 2025, he and his colleagues reached a settlement that prohibits police officers from doing what they did in Scruggs’s case—stopping or searching people simply because they are near the location of a gunshot detection alert. Chicago had already decommissioned ShotSpotter in 2024, but the agreement will cover any future gunshot detection systems. Manes is carefully watching to see what happens next. Though Manes is pleased with the settlement, he points out that it narrowly focused on how police resources were used after the gunshot detection system was operational. “There is a need for much broader structural change to how the city chooses to use surveillance technology and then deploys it,” he adds. He supports laws that require disclosure from local officials and law enforcement about what technologies are being proposed and how civil rights could be affected. More than two dozen jurisdictions nationwide have adopted surveillance transparency laws, including San Francisco, Seattle, Boston, and New York City. But so far Chicago is not on that list. Rod McCullom is a Chicago-based science and technology writer whose focus areas include AI, biometrics, cognition, and the science of crime and violence.