Scottish startup Myriad Wind is advancing a multi-rotor wind turbine design which it believes will help the wind industry tackle ongoing profitability challenges.

Founded in 2021 by three PhD students, Myriad says its “game-changing” technology can deliver utility-scale wind energy without the need for large components.

The Stirling-based company says its multi-rotor design can reduce manufacturing, maintenance and installation costs compared to conventional turbines.

In addition, Myriad says its turbines can achieve this while improving both sustainability and increasing energy yield, vital for driving down the cost of energy.

Myriad has already raised £725,000 from a mixture of equity and grand funding, and is currently halfway to completing a £1 million equity to progress to a 1 MW pilot project.

Speaking to Energy Voice, Myriad Wind co-founder and chief executive Adam Harris said the technology could be an answer to some of the profitability challenges facing the wind sector.

In recent years the offshore wind industry has grappled with rising costs, supply chain issues and high interest rates, putting many projects at risk of cancellation.

© Supplied by Ross Johnston/Newsli

© Supplied by Ross Johnston/NewsliThese problems have been compounded by challenges facing project developers, including planning delays, lengthy grid connection queues and vessels shortages.

The rising costs and profitability challenges have led to offshore oil and gas giants including BP, Shell and Equinor to significantly scale back their wind investments.

Even traditional wind players such as Denmark’s Ørsted, Sweden’s Vattenfall and Germany’s RWE have not been immune from the sector’s profitability crunch.

And while the Labour government has removed a ban on onshore wind in England, skill shortages, community backlash and planning constraints remain hurdles.

Multi-rotor wind turbines

But according to Harris, many of the wind sector’s current challenges stem from the fact that modern turbines are simply getting too big.

In recent years, the capacity of many offshore turbine models has surpassed 20 MW, with Chinese firm Dongfang Electric unveiling a 26 MW model in October 2024.

Meanwhile, offshore blades from firms like Vestas and Mingyang now commonly exceed 100 metres in length.

Onshore wind turbines are also increasing in size, creating increasingly complicated and expensive logistics challenges for developers on land and at sea.

© Supplied by Collett

© Supplied by CollettHarris said organising the transportation alone for a hundred megawatt onshore wind farm can take up to 12 months in the UK.

“That’s just simply because every single landowner that a blade crosses over for oversailing has to agree to that happening, and also be compensated for it,” he said.

“It just takes one person to say ‘no’, that you then need to reroute the whole thing around the other way.”

Harris said he spoke to one developer in England who had a project stalled because the turbines were “literally one inch away” from scraping buildings on the route to the site.

Myriad, on the other hand, has designed its multi-rotor components to fit within a standard lorry, substantially reducing the complexity of transporting turbines to site.

Wind turbine manufacturing

Attaching multiple smaller rotors to a lattice frame structure also creates greater efficiencies in manufacturing, Harris.

Wind developers are currently facing huge order backlogs from turbine manufacturers, and Harris said increases in raw materials costs and the mismatch between demand and supply is leading to price increases of up to 35% over the past four years.

Current manufacturing techniques in the industry are also “very expensive”, Harris said, and can take up to 14 days for a single blade.

“They’re actually built by hand because the process can’t be automated, which is nuts when you think about it,” he said.

© Supplied by Forth Ports

© Supplied by Forth Ports“Building a 120 metre blade by hand, that is really crazy.”

Focusing on building a larger number of smaller turbines would help to bring down costs by allowing for automation, Harris said.

“We could build a four rotor system with 250 kW rotors to make a 1 MW, or we could build a 24 rotor system using that same turbine to make a 6 MW,” he said.

“In terms of supply chain, that’s a lot more efficient to do and it means we can drive huge efficiencies there and also reduce the bottlenecks which are causing these backlogs.”

UK supply chain

Overall, Harris said Myriad believes its design can reduce capital expenditure costs by 10% for a 6 MW wind turbine.

In addition, Harris said the simplified manufacturing process could provide opportunities for increased UK content Myriad’s blades and frames.

“We’re now talking about 13 metre blade, which any company that’s building fibreglass hulls for sailing yachts could do,” he said.

Smaller blades would also allow manufacturers to use materials which are easier to recycle, improving sustainability and reducing costs further, he said.

With the UK government set to introduce incentives for local content from the seventh renewables allocation round (AR7) this year, Harris believes there is an opportunity for developers to win over communities that are often sceptical of the benefits wind projects provide.

Wind operations and maintenance costs

While the Myriad design has more moving parts, Harris said because the use of a frame mount removes the need to hire expensive cranes or jacket vessels for maintenance.

“Jacket vessels cost heaven and earth,” he said.

© Supplied by Ocean Winds

© Supplied by Ocean Winds“This is one of the reasons why floating is so attractive for multi-rotors because at the moment you can’t really maintain floating wind turbines unless you bring them back to port.”

Alongside these cost reductions, Harris said research shows multi-rotor wind turbines also provide aerodynamic benefits compared to single-rotor designs.

As a result, altogether Harris estimates one of its 6 MW onshore wind turbines can increase net profit for developers by up to 30%.

“This isn’t just a logistics solution…, it’s also really the next step change in wind cost-effectiveness,” he said.

Myriad growth plans

While Myriad is currently focusing on UK and European onshore developers, Harris said the startup has attracted interest from as far afield as Africa and South America.

While logistics are a challenge across Europe, Harris said there are other parts of the world “where it’s an even greater challenge”.

With a Myriad system using a standard HGV for transport, Harris said it opens up many more sites for potential wind farm development.

© Supplied by Myriad Wind

© Supplied by Myriad WindIn the near future, Myriad plans to build on the success of its first 50 kW pilot turbine and construct a 1 MW 10-rotor demonstrator by 2027.

From there, Harris said the company plans to scale up to commercialise its turbines for further onshore projects.

Myriad plans to initially focus on the distributed wind market including farms, distilleries and data centres.

“We’ve got a test site ready to go, we’ve got suppliers ready to go, we’ve got a plan ready to go, we’re just looking for that capital to make it happen now,” he said.

Myriad’s offshore wind potential

In the longer term, Harris said Myriad plans to expand into the offshore wind sector as well, including the emerging floating wind sector.

Harris said many firms across the North Sea oil and gas industry are questioning how profitable transitioning into offshore wind work will be for them.

“That’s where we think there’s a wider industry opportunity for us to really show that if you maybe change the way we do things, we can make it profitable,” he said.

“Not just for the developers, but also for the manufacturers and the wider supply chain.”

Myriad isn’t the only firm with an eye on the floating wind market.

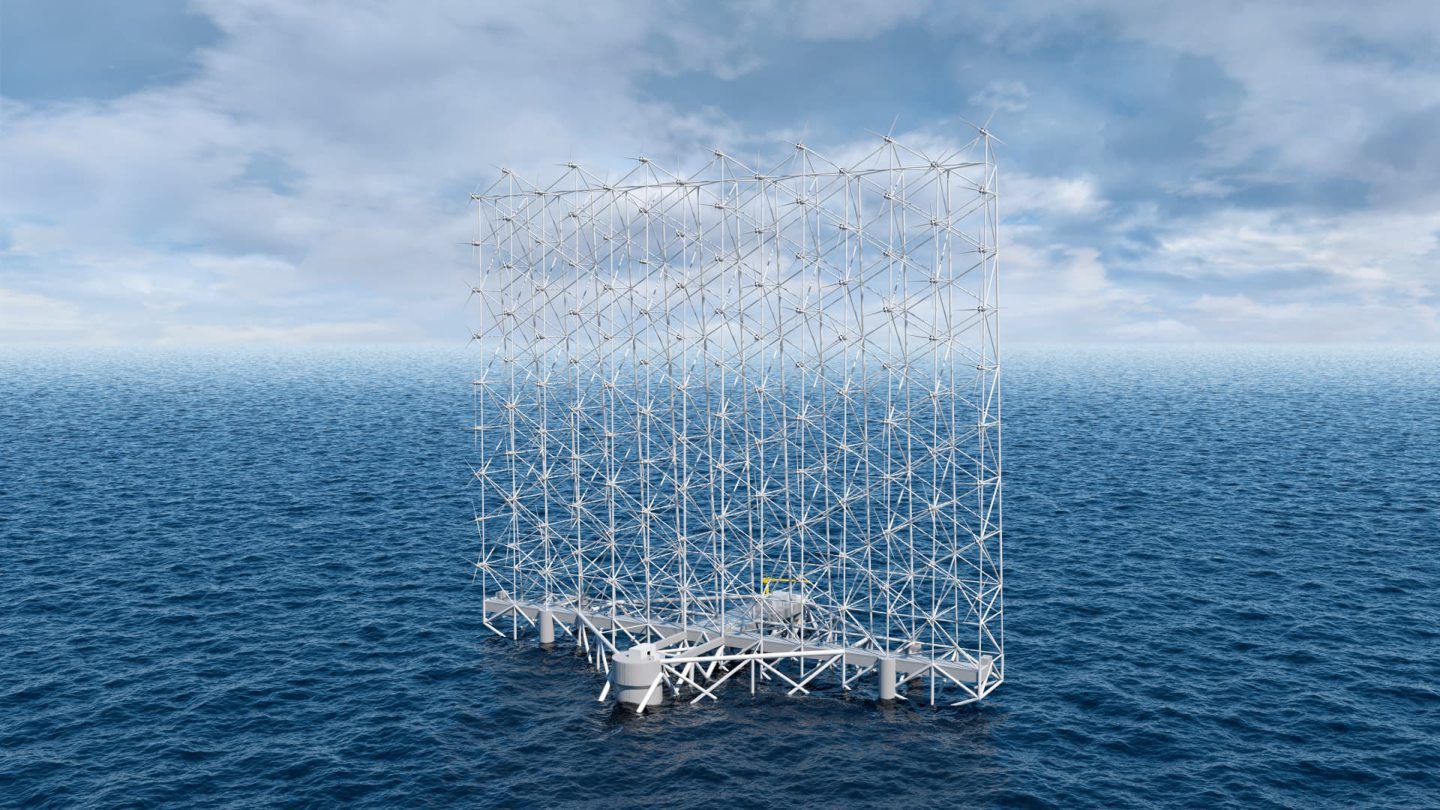

Norwegian multi-rotor developer Wind Catching received a 1.2bn NOK (£85m) grant from the Norwegian government to build a demonstrator project in the North Sea.

© Supplied by Wind Catching System

© Supplied by Wind Catching SystemThe collaboration with German firm EnBW will see 40 turbines with 1 MW output combined into a floating ‘Windcatcher’ around 22km off the coast of Øygarden.

Net zero goals

Harris said while Myriad is taking a “different approach” to Wind Catching, he said the Norwegian government’s backing of multi-rotor technology is “fantastic”.

“[It’s] really great validation that there is something here and if we put the money in, it’s going to happen and we are going to make this work,” he said.

“And the difference we could make for the UK could be huge.”

But alongside the commercial imperative, Harris said Myriad is also focused on helping the industry to reach its climate and net zero goals.

“At the moment, there’s just not the capacity to build and to manufacture enough turbines to reach net zero,” he said.

“If we really want to take net zero seriously… maybe something like the Myriad turbine is a better way to build out more capacity, faster, for a lower cost.

“It would be too much to say that we’d replace [single-rotor] technology completely, but I’d be very surprised if multi-rotors weren’t playing a significant role in the market in 10-15 years time.”