As many of us are ramping up with shopping, baking, and planning for the holiday season, nuclear power plants are also getting ready for one of their busiest seasons of the year.

Here in the US, nuclear reactors follow predictable seasonal trends. Summer and winter tend to see the highest electricity demand, so plant operators schedule maintenance and refueling for other parts of the year.

This scheduled regularity might seem mundane, but it’s quite the feat that operational reactors are as reliable and predictable as they are. It leaves some big shoes to fill for next-generation technology hoping to join the fleet in the next few years.

Generally, nuclear reactors operate at constant levels, as close to full capacity as possible. In 2024, for commercial reactors worldwide, the average capacity factor—the ratio of actual energy output to the theoretical maxiumum—was 83%. North America rang in at an average of about 90%.

(I’ll note here that it’s not always fair to just look at this number to compare different kinds of power plants—natural-gas plants can have lower capacity factors, but it’s mostly because they’re more likely to be intentionally turned on and off to help meet uneven demand.)

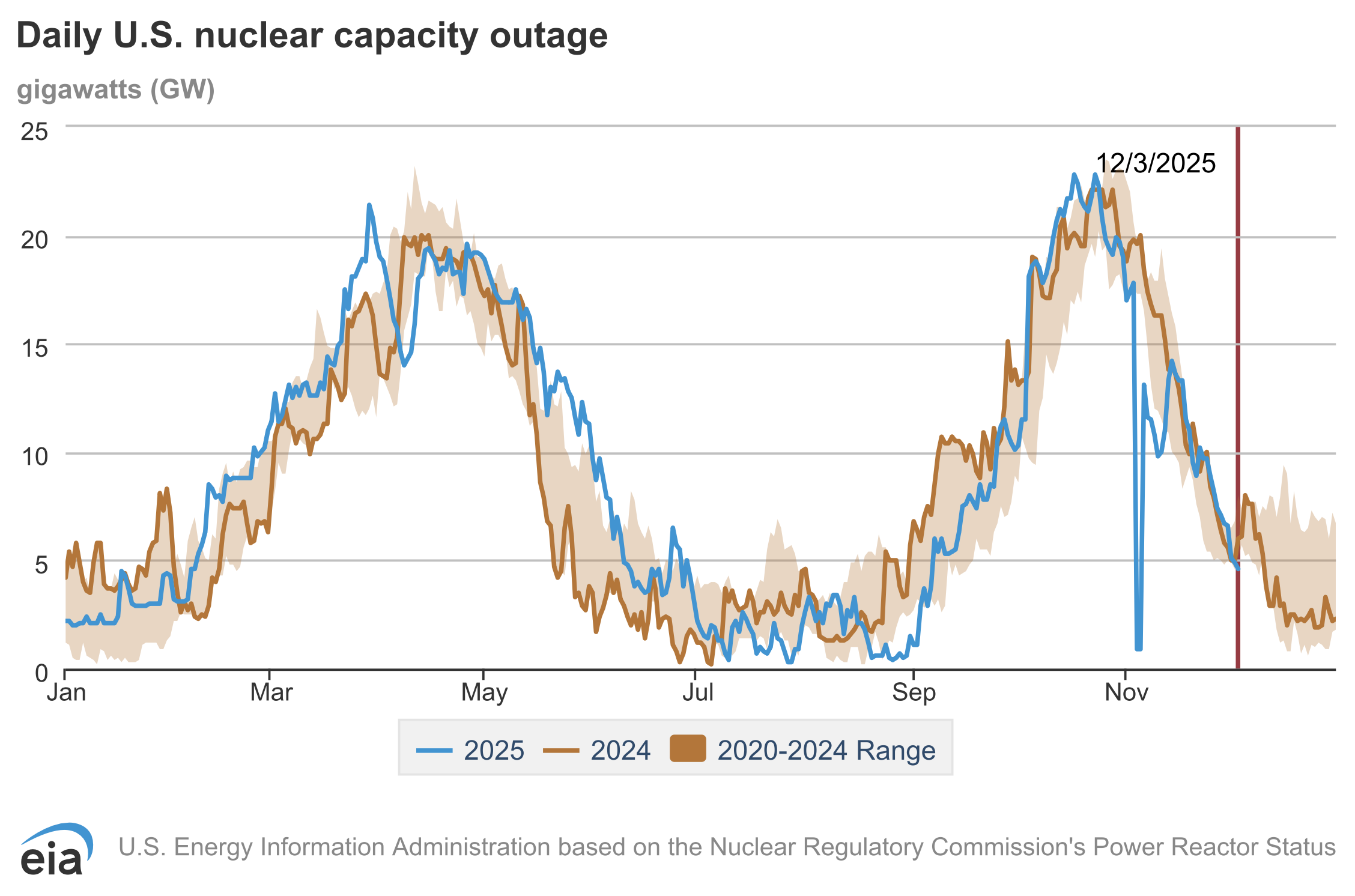

Those high capacity factors also undersell the fleet’s true reliability—a lot of the downtime is scheduled. Reactors need to refuel every 18 to 24 months, and operators tend to schedule those outages for the spring and fall, when electricity demand isn’t as high as when we’re all running our air conditioners or heaters at full tilt.

Take a look at this chart of nuclear outages from the US Energy Information Administration. There are some days, especially at the height of summer, when outages are low, and nearly all commercial reactors in the US are operating at nearly full capacity. On July 28 of this year, the fleet was operating at 99.6%. Compare that with the 77.6% of capacity on October 18, as reactors were taken offline for refueling and maintenance. Now we’re heading into another busy season, when reactors are coming back online and shutdowns are entering another low point.

That’s not to say all outages are planned. At the Sequoyah nuclear power plant in Tennessee, a generator failure in July 2024 took one of two reactors offline, an outage that lasted nearly a year. (The utility also did some maintenance during that time to extend the life of the plant.) Then, just days after that reactor started back up, the entire plant had to shut down because of low water levels.

And who can forget the incident earlier this year when jellyfish wreaked havoc on not one but two nuclear power plants in France? In the second instance, the squishy creatures got into the filters of equipment that sucks water out of the English Channel for cooling at the Paluel nuclear plant. They forced the plant to cut output by nearly half, though it was restored within days.

Barring jellyfish disasters and occasional maintenance, the global nuclear fleet operates quite reliably. That wasn’t always the case, though. In the 1970s, reactors operated at an average capacity factor of just 60%. They were shut down nearly as often as they were running.

The fleet of reactors today has benefited from decades of experience. Now we’re seeing a growing pool of companies aiming to bring new technologies to the nuclear industry.

Next-generation reactors that use new materials for fuel or cooling will be able to borrow some lessons from the existing fleet, but they’ll also face novel challenges.

That could mean early demonstration reactors aren’t as reliable as the current commercial fleet at first. “First-of-a-kind nuclear, just like with any other first-of-a-kind technologies, is very challenging,” says Koroush Shirvan, a professor of nuclear science and engineering at MIT.

That means it will probably take time for molten-salt reactors or small modular reactors, or any of the other designs out there to overcome technical hurdles and settle into their own rhythm. It’s taken decades to get to a place where we take it for granted that the nuclear fleet can follow a neat seasonal curve based on electricity demand.

There will always be hurricanes and electrical failures and jellyfish invasions that cause some unexpected problems and force nuclear plants (or any power plants, for that matter) to shut down. But overall, the fleet today operates at an extremely high level of consistency. One of the major challenges ahead for next-generation technologies will be proving that they can do the same.

This article is from The Spark, MIT Technology Review’s weekly climate newsletter. To receive it in your inbox every Wednesday, sign up here.