Consider, if you will, the translucent blob in the eye of a microscope: a human blastocyst, the biological specimen that emerges just five days or so after a fateful encounter between egg and sperm. This bundle of cells, about the size of a grain of sand pulled from a powdery white Caribbean beach, contains the coiled potential of a future life: 46 chromosomes, thousands of genes, and roughly six billion base pairs of DNA—an instruction manual to assemble a one-of-a-kind human.

Now imagine a laser pulse snipping a hole in the blastocyst’s outermost shell so a handful of cells can be suctioned up by a microscopic pipette. This is the moment, thanks to advances in genetic sequencing technology, when it becomes possible to read virtually that entire instruction manual.

An emerging field of science seeks to use the analysis pulled from that procedure to predict what kind of a person that embryo might become. Some parents turn to these tests to avoid passing on devastating genetic disorders that run in their families. A much smaller group, driven by dreams of Ivy League diplomas or attractive, well-behaved offspring, are willing to pay tens of thousands of dollars to optimize for intelligence, appearance, and personality. Some of the most eager early boosters of this technology are members of the Silicon Valley elite, including tech billionaires like Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, and Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong.

Embryo selection is less like a build-a-baby workshop and more akin to a store where parents can shop for their future children from several available models—complete with stat cards.

But customers of the companies emerging to provide it to the public may not be getting what they’re paying for. Genetics experts have been highlighting the potential deficiencies of this testing for years. A 2021 paper by members of the European Society of Human Genetics said, “No clinical research has been performed to assess its diagnostic effectiveness in embryos. Patients need to be properly informed on the limitations of this use.” And a paper published this May in the Journal of Clinical Medicine echoed this concern and expressed particular reservations about screening for psychiatric disorders and non-disease-related traits: “Unfortunately, no clinical research has to date been published comprehensively evaluating the effectiveness of this strategy [of predictive testing]. Patient awareness regarding the limitations of this procedure is paramount.”

Moreover, the assumptions underlying some of this work—that how a person turns out is the product not of privilege or circumstance but of innate biology—have made these companies a political lightning rod.

As this niche technology begins to make its way toward the mainstream, scientists and ethicists are racing to confront the implications—for our social contract, for future generations, and for our very understanding of what it means to be human.

Preimplantation genetic testing (PGT), while still relatively rare, is not new. Since the 1990s, parents undergoing in vitro fertilization have been able to access a number of genetic tests before choosing which embryo to use. A type known as PGT-M can detect single-gene disorders like cystic fibrosis, sickle cell anemia, and Huntington’s disease. PGT-A can ascertain the sex of an embryo and identify chromosomal abnormalities that can lead to conditions like Down syndrome or reduce the chances that an embryo will implant successfully in the uterus. PGT-SR helps parents avoid embryos with issues such as duplicated or missing segments of the chromosome.

Those tests all identify clear-cut genetic problems that are relatively easy to detect, but most of the genetic instruction manual included in an embryo is written in far more nuanced code. In recent years, a fledgling market has sprung up around a new, more advanced version of the testing process called PGT-P: preimplantation genetic testing for polygenic disorders (and, some claim, traits)—that is, outcomes determined by the elaborate interaction of hundreds or thousands of genetic variants.

In 2020, the first baby selected using PGT-P was born. While the exact figure is unknown, estimates put the number of children who have now been born with the aid of this technology in the hundreds. As the technology is commercialized, that number is likely to grow.

Embryo selection is less like a build-a-baby workshop and more akin to a store where parents can shop for their future children from several available models—complete with stat cards indicating their predispositions.

A handful of startups, armed with tens of millions of dollars of Silicon Valley cash, have developed proprietary algorithms to compute these stats—analyzing vast numbers of genetic variants and producing a “polygenic risk score” that shows the probability of an embryo developing a variety of complex traits.

For the last five years or so, two companies—Genomic Prediction and Orchid—have dominated this small landscape, focusing their efforts on disease prevention. But more recently, two splashy new competitors have emerged: Nucleus Genomics and Herasight, which have rejected the more cautious approach of their predecessors and waded into the controversial territory of genetic testing for intelligence. (Nucleus also offers tests for a wide variety of other behavioral and appearance-related traits.)

The practical limitations of polygenic risk scores are substantial. For starters, there is still a lot we don’t understand about the complex gene interactions driving polygenic traits and disorders. And the biobank data sets they are based on tend to overwhelmingly represent individuals with Western European ancestry, making it more difficult to generate reliable scores for patients from other backgrounds. These scores also lack the full context of environment, lifestyle, and the myriad other factors that can influence a person’s characteristics. And while polygenic risk scores can be effective at detecting large, population-level trends, their predictive abilities drop significantly when the sample size is as tiny as a single batch of embryos that share much of the same DNA.

The medical community—including organizations like the American Society of Human Genetics, the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine—is generally wary of using polygenic risk scores for embryo selection. “The practice has moved too fast with too little evidence,” the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics wrote in an official statement in 2024.

But beyond questions of whether evidence supports the technology’s effectiveness, critics of the companies selling it accuse them of reviving a disturbing ideology: eugenics, or the belief that selective breeding can be used to improve humanity. Indeed, some of the voices who have been most confident that these methods can successfully predict nondisease traits have made startling claims about natural genetic hierarchies and innate racial differences.

What everyone can agree on, though, is that this new wave of technology is helping to inflame a centuries-old debate over nature versus nurture.

The term “eugenics” was coined in 1883 by a British anthropologist and statistician named Sir Francis Galton, inspired in part by the work of his cousin Charles Darwin. He derived it from a Greek word meaning “good in stock, hereditarily endowed with noble qualities.”

Some of modern history’s darkest chapters have been built on Galton’s legacy, from the Holocaust to the forced sterilization laws that affected certain groups in the United States well into the 20th century. Modern science has demonstrated the many logical and empirical problems with Galton’s methodology. (For starters, he counted vague concepts like “eminence”—as well as infections like syphilis and tuberculosis—as heritable phenotypes, meaning characteristics that result from the interaction of genes and environment.)

Yet even today, Galton’s influence lives on in the field of behavioral genetics, which investigates the genetic roots of psychological traits. Starting in the 1960s, researchers in the US began to revisit one of Galton’s favorite methods: twin studies. Many of these studies, which analyzed pairs of identical and fraternal twins to try to determine which traits were heritable and which resulted from socialization, were funded by the US government. The most well-known of these, the Minnesota Twin Study, also accepted grants from the Pioneer Fund, a now defunct nonprofit that had promoted eugenics and “race betterment” since its founding in 1937.

The nature-versus-nurture debate hit a major inflection point in 2003, when the Human Genome Project was declared complete. After 13 years and at a cost of nearly $3 billion, an international consortium of thousands of researchers had sequenced 92% of the human genome for the first time.

Today, the cost of sequencing a genome can be as low as $600, and one company says it will soon drop even further. This dramatic reduction has made it possible to build massive DNA databases like the UK Biobank and the National Institutes of Health’s All of Us, each containing genetic data from more than half a million volunteers. Resources like these have enabled researchers to conduct genome-wide association studies, or GWASs, which identify correlations between genetic variants and human traits by analyzing single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)—the most common form of genetic variation between individuals. The findings from these studies serve as a reference point for developing polygenic risk scores.

Most GWASs have focused on disease prevention and personalized medicine. But in 2011, a group of medical researchers, social scientists, and economists launched the Social Science Genetic Association Consortium (SSGAC) to investigate the genetic basis of complex social and behavioral outcomes. One of the phenotypes they focused on was the level of education people reached.

“It was a bit of a phenotype of convenience,” explains Patrick Turley, an economist and member of the steering committee at SSGAC, given that educational attainment is routinely recorded in surveys when genetic data is collected. Still, it was “clear that genes play some role,” he says. “And trying to understand what that role is, I think, is really interesting.” He adds that social scientists can also use genetic data to try to better “understand the role that is due to nongenetic pathways.”

Many on the left are generally willing to allow that any number of traits, from addiction to obesity, are genetically influenced. Yet heritable cognitive ability seems to be “beyond the pale for us to integrate as a source of difference.”

The work immediately stirred feelings of discomfort—not least among the consortium’s own members, who feared that they might unintentionally help reinforce racism, inequality, and genetic determinism.

It’s also created quite a bit of discomfort in some political circles, says Kathryn Paige Harden, a psychologist and behavioral geneticist at the University of Texas in Austin, who says she has spent much of her career making the unpopular argument to fellow liberals that genes are relevant predictors of social outcomes.

Harden thinks a strength of those on the left is their ability to recognize “that bodies are different from each other in a way that matters.” Many are generally willing to allow that any number of traits, from addiction to obesity, are genetically influenced. Yet, she says, heritable cognitive ability seems to be “beyond the pale for us to integrate as a source of difference that impacts our life.”

Harden believes that genes matter for our understanding of traits like intelligence, and that this should help shape progressive policymaking. She gives the example of an education department seeking policy interventions to improve math scores in a given school district. If a polygenic risk score is “as strongly correlated with their school grades” as family income is, she says of the students in such a district, then “does deliberately not collecting that [genetic] information, or not knowing about it, make your research harder [and] your inferences worse?”

To Harden, persisting with this strategy of avoidance for fear of encouraging eugenicists is a mistake. If “insisting that IQ is a myth and genes have nothing to do with it was going to be successful at neutralizing eugenics,” she says, “it would’ve won by now.”

Part of the reason these ideas are so taboo in many circles is that today’s debate around genetic determinism is still deeply infused with Galton’s ideas—and has become a particular fixation among the online right.

After Elon Musk took over Twitter (now X) in 2022 and loosened its restrictions on hate speech, a flood of accounts started sharing racist posts, some speculating about the genetic origins of inequality while arguing against immigration and racial integration. Musk himself frequently reposts and engages with accounts like Crémieux Recueil, the pen name of independent researcher Jordan Lasker, who has written about the “Black-White IQ gap,” and i/o, an anonymous account that once praised Musk for “acknowledging data on race and crime,” saying it “has done more to raise awareness of the disproportionalities observed in these data than anything I can remember.” (In response to allegations that his research encourages eugenics, Lasker wrote to MIT Technology Review, “The popular understanding of eugenics is about coercion and cutting people cast as ‘undesirable’ out of the breeding pool. This is nothing like that, so it doesn’t qualify as eugenics by that popular understanding of the term.” After going to print, i/o wrote in an email, “Just because differences in intelligence at the individual level are largely heritable, it does not mean that group differences in measured intelligence … are due to genetic differences between groups,” but that the latter is not “scientifically settled” and “an extremely important (and necessary) research area that should be funded rather than made taboo.” He added, “I’ve never made any argument against racial integration or intermarriage or whatever.” X and Musk did not respond to requests for comment.)

Harden, though, warns against discounting the work of an entire field because of a few noisy neoreactionaries. “I think there can be this idea that technology is giving rise to the terrible racism,” she says. The truth, she believes, is that “the racism has preexisted any of this technology.”

In 2019, a company called Genomic Prediction began to offer the first preimplantation polygenic testing that had ever been made commercially available. With its LifeView Embryo Health Score, prospective parents are able to assess their embryos’ predisposition to genetically complex health problems like cancer, diabetes, and heart disease. Pricing for the service starts at $3,500. Genomic Prediction uses a technique called an SNP array, which targets specific sites in the genome where common variants occur. The results are then cross-checked against GWASs that show correlations between genetic variants and certain diseases.

Four years later, a company named Orchid began offering a competing test. Orchid’s Whole Genome Embryo Report distinguished itself by claiming to sequence more than 99% of an embryo’s genome, allowing it to detect novel mutations and, the company says, diagnose rare diseases more accurately. For $2,500 per embryo, parents can access polygenic risk scores for 12 disorders, including schizophrenia, breast cancer, and hypothyroidism.

Orchid was founded by a woman named Noor Siddiqui. Before getting undergraduate and graduate degrees from Stanford, she was awarded the Thiel fellowship—a $200,000 grant given to young entrepreneurs willing to work on their ideas instead of going to college—back when she was a teenager, in 2012. This set her up to attract attention from members of the tech elite as both customers and financial backers. Her company has raised $16.5 million to date from investors like Ethereum founder Vitalik Buterin, former Coinbase CTO Balaji Srinivasan, and Armstrong, the Coinbase CEO.

In August Siddiqui made the controversial suggestion that parents who choose not to use genetic testing might be considered irresponsible. “Just be honest: you’re okay with your kid potentially suffering for life so you can feel morally superior …” she wrote on X.

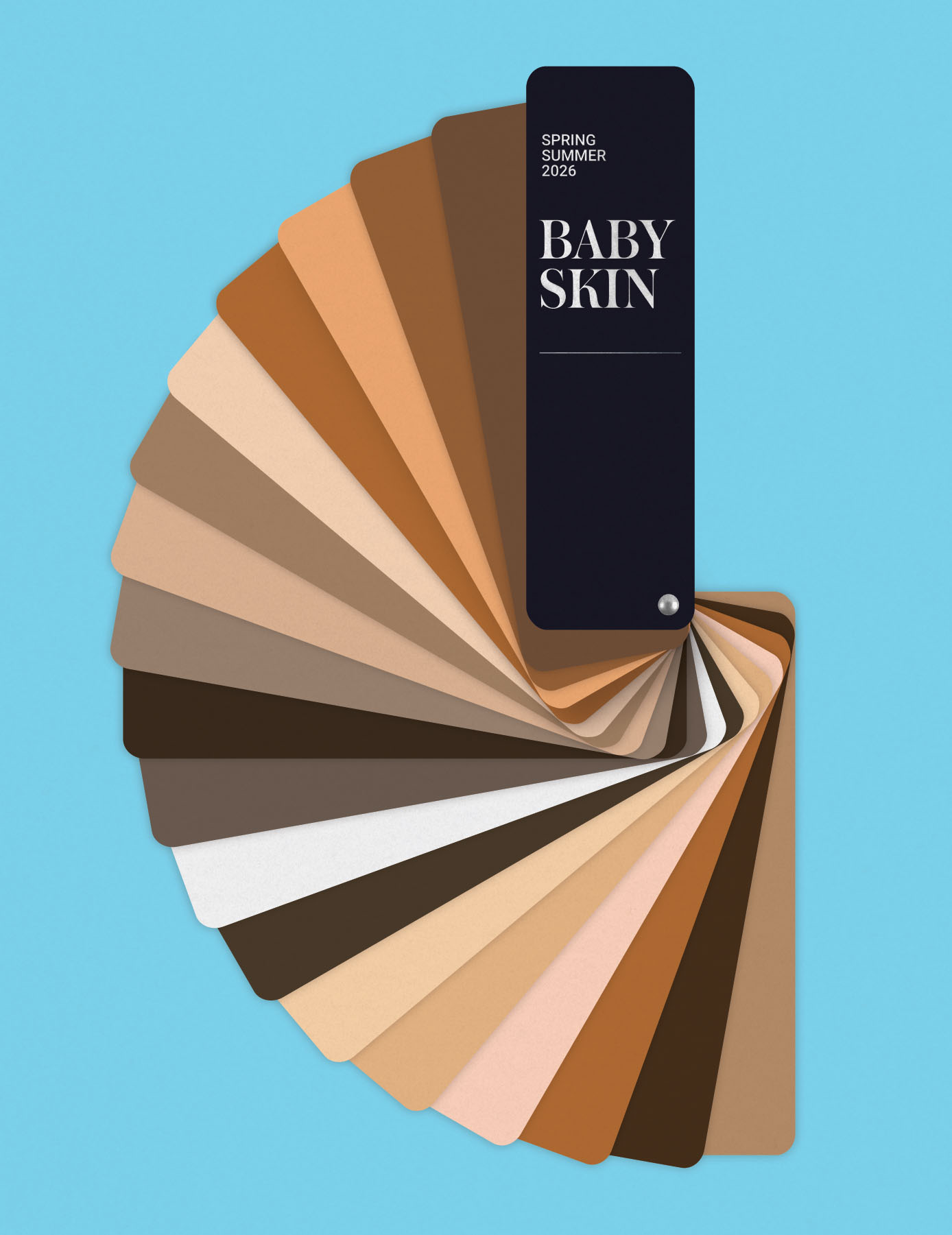

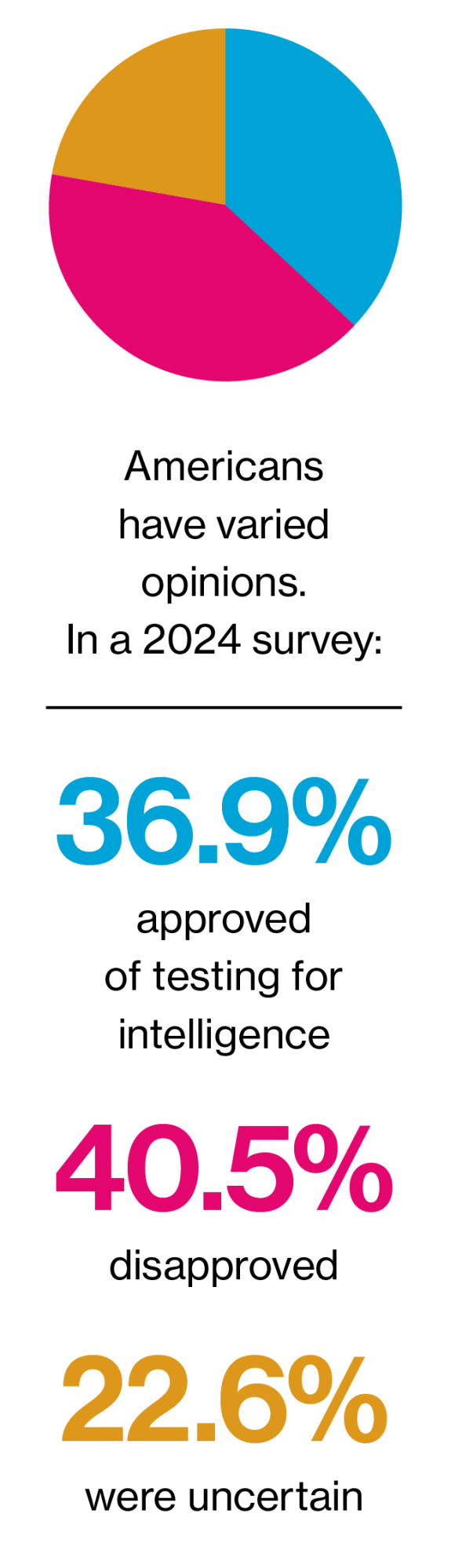

Americans have varied opinions on the emerging technology. In 2024, a group of bioethicists surveyed 1,627 US adults to determine attitudes toward a variety of polygenic testing criteria. A large majority approved of testing for physical health conditions like cancer, heart disease, and diabetes. Screening for mental health disorders, like depression, OCD, and ADHD, drew a more mixed—but still positive—response. Appearance-related traits, like skin color, baldness, and height, received less approval as something to test for.

Intelligence was among the most contentious traits—unsurprising given the way it has been weaponized throughout history and the lack of cultural consensus on how it should even be defined. (In many countries, intelligence testing for embryos is heavily regulated; in the UK, the practice is banned outright.) In the 2024 survey, 36.9% of respondents approved of preimplantation genetic testing for intelligence, 40.5% disapproved, and 22.6% said they were uncertain.

Despite the disagreement, intelligence has been among the traits most talked about as targets for testing. From early on, Genomic Prediction says, it began receiving inquiries “from all over the world” about testing for intelligence, according to Diego Marin, the company’s head of global business development and scientific affairs.

At one time, the company offered a predictor for what it called “intellectual disability.” After some backlash questioning both the predictive capacity and the ethics of these scores, the company discontinued the feature. “Our mission and vision of this company is not to improve [a baby], but to reduce risk for disease,” Marin told me. “When it comes to traits about IQ or skin color or height or something that’s cosmetic and doesn’t really have a connotation of a disease, then we just don’t invest in it.”

Orchid, on the other hand, does test for genetic markers associated with intellectual disability and developmental delay. But that may not be all. According to one employee of the company, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, intelligence testing is also offered to “high-roller” clients. According to this employee, another source close to the company, and reporting in the Washington Post, Musk used Orchid’s services in the conception of at least one of the children he shares with the tech executive Shivon Zilis. (Orchid, Musk, and Zilis did not respond to requests for comment.)

I met Kian Sadeghi, the 25-year-old founder of New York–based Nucleus Genomics, on a sweltering July afternoon in his SoHo office. Slight and kinetic, Sadeghi spoke at a machine-gun pace, pausing only occasionally to ask if I was keeping up.

Sadeghi had modified his first organism—a sample of brewer’s yeast—at the age of 16. As a high schooler in 2016, he was taking a course on CRISPR-Cas9 at a Brooklyn laboratory when he fell in love with the “beautiful depth” of genetics. Just a few years later, he dropped out of college to build “a better 23andMe.”

His company targets what you might call the application layer of PGT-P, accepting data from IVF clinics—and even from the competitors mentioned in this story—and running its own computational analysis.

“Unlike a lot of the other testing companies, we’re software first, and we’re consumer first,” Sadeghi told me. “It’s not enough to give someone a polygenic score. What does that mean? How do you compare them? There’s so many really hard design problems.”

Like its competitors, Nucleus calculates its polygenic risk scores by comparing an individual’s genetic data with trait-associated variants identified in large GWASs, providing statistically informed predictions.

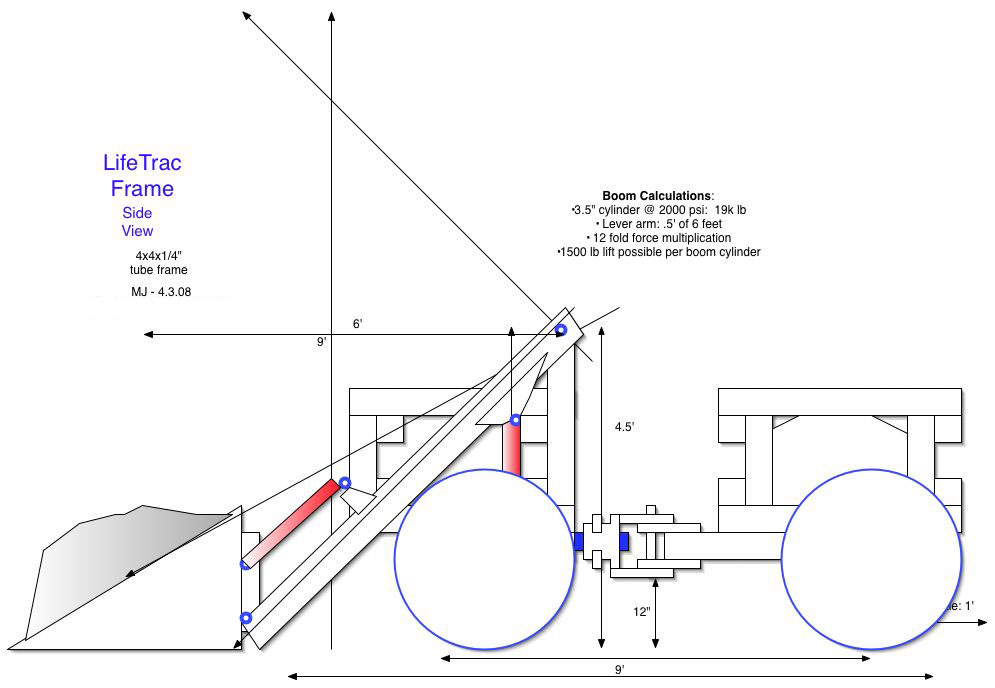

Nucleus provides two displays of a patient’s results: a Z-score, plotted from –4 to 4, which explains the risk of a certain trait relative to a population with similar genetic ancestry (for example, if Embryo #3 has a 2.1 Z-score for breast cancer, its risk is higher than average), and an absolute risk score, which includes relevant clinical factors (Embryo #3 has a minuscule actual risk of breast cancer, given that it is male).

The real difference between Nucleus and its competitors lies in the breadth of what it claims to offer clients. On its sleek website, prospective parents can sort through more than 2,000 possible diseases, as well as traits from eye color to IQ. Access to the Nucleus Embryo platform costs $8,999, while the company’s new IVF+ offering—which includes one IVF cycle with a partner clinic, embryo screening for up to 20 embryos, and concierge services throughout the process—starts at $24,999.

“Maybe you want your baby to have blue eyes versus green eyes,” Nucleus founder Kian Sadeghi said at a June event. “That is up to the liberty of the parents.”

Its promises are remarkably bold. The company claims to be able to forecast a propensity for anxiety, ADHD, insomnia, and other mental issues. It says you can see which of your embryos are more likely to have alcohol dependence, which are more likely to be left-handed, and which might end up with severe acne or seasonal allergies. (Nevertheless, at the time of writing, the embryo-screening platform provided this disclaimer: “DNA is not destiny. Genetics can be a helpful tool for choosing an embryo, but it’s not a guarantee. Genetic research is still in it’s [sic] infancy, and there’s still a lot we don’t know about how DNA shapes who we are.”)

To people accustomed to sleep trackers, biohacking supplements, and glucose monitoring, taking advantage of Nucleus’s options might seem like a no-brainer. To anyone who welcomes a bit of serendipity in their life, this level of perceived control may be disconcerting to say the least.

Sadeghi likes to frame his arguments in terms of personal choice. “Maybe you want your baby to have blue eyes versus green eyes,” he told a small audience at Nucleus Embryo’s June launch event. “That is up to the liberty of the parents.”

On the official launch day, Sadeghi spent hours gleefully sparring with X users who accused him of practicing eugenics. He rejects the term, favoring instead “genetic optimization”—though it seems he wasn’t too upset about the free viral marketing. “This week we got five million impressions on Twitter,” he told a crowd at the launch event, to a smattering of applause. (In an email to MIT Technology Review, Sadeghi wrote, “The history of eugenics is one of coercion and discrimination by states and institutions; what Nucleus does is the opposite—genetic forecasting that empowers individuals to make informed decisions.”)

Nucleus has raised more than $36 million from investors like Srinivasan, Alexis Ohanian’s venture capital firm Seven Seven Six, and Thiel’s Founders Fund. (Like Siddiqui, Sadeghi was a recipient of a Thiel fellowship when he dropped out of college; a representative for Thiel did not respond to a request for comment for this story.) Sadeghi has even poached Genomic Prediction’s cofounder Nathan Treff, who is now Nucleus’s chief clinical officer.

Sadeghi’s real goal is to build a one-stop shop for every possible application of genetic sequencing technology, from genealogy to precision medicine to genetic engineering. He names a handful of companies providing these services, with a combined market cap in the billions. “Nucleus is collapsing all five of these companies into one,” he says. “We are not an IVF testing company. We are a genetic stack.”

This spring, I elbowed my way into a packed hotel bar in the Flatiron district, where over a hundred people had gathered to hear a talk called “How to create SUPERBABIES.” The event was part of New York’s Deep Tech Week, so I expected to meet a smattering of biotech professionals and investors. Instead, I was surprised to encounter a diverse and curious group of creatives, software engineers, students, and prospective parents—many of whom had come with no previous knowledge of the subject.

The speaker that evening was Jonathan Anomaly, a soft-spoken political philosopher whose didactic tone betrays his years as a university professor.

Some of Anomaly’s academic work has focused on developing theories of rational behavior. At Duke and the University of Pennsylvania, he led introductory courses on game theory, ethics, and collective action problems as well as bioethics, digging into thorny questions about abortion, vaccines, and euthanasia. But perhaps no topic has interested him so much as the emerging field of genetic enhancement.

In 2018, in a bioethics journal, Anomaly published a paper with the intentionally provocative title “Defending Eugenics.” He sought to distinguish what he called “positive eugenics”—noncoercive methods aimed at increasing traits that “promote individual and social welfare”—from the so-called “negative eugenics” we know from our history books.

Anomaly likes to argue that embryo selection isn’t all that different from practices we already take for granted. Don’t believe two cousins should be allowed to have children? Perhaps you’re a eugenicist, he contends. Your friend who picked out a six-foot-two Harvard grad from a binder of potential sperm donors? Same logic.

His hiring at the University of Pennsylvania in 2019 caused outrage among some students, who accused him of “racial essentialism.” In 2020, Anomaly left academia, lamenting that “American universities had become an intellectual prison.”

A few years later, Anomaly joined a nascent PGT-P company named Herasight, which was promising to screen for IQ.

At the end of July, the company officially emerged from stealth mode. A representative told me that most of the money raised so far is from angel investors, including Srinivasan, who also invested in Orchid and Nucleus. According to the launch announcement on X, Herasight has screened “hundreds of embryos” for private customers and is beginning to offer its first publicly available consumer product, a polygenic assessment that claims to detect an embryo’s likelihood of developing 17 diseases.

Their marketing materials boast predictive abilities 122% better than Orchid’s and 193% better than Genomic Prediction’s for this set of diseases. (“Herasight is comparing their current predictor to models we published over five years ago,” Genomic Prediction responded in a statement. “Our team is confident our predictors are world-class and are not exceeded in quality by any other lab.”)

The company did not include comparisons with Nucleus, pointing to the “absence of published performance validations” by that company and claiming it represented a case where “marketing outpaces science.” (“Nucleus is known for world-class science and marketing, and we understand why that’s frustrating to our competitors,” a representative from the company responded in a comment.)

Herasight also emphasized new advances in “within-family validation” (making sure that the scores are not merely picking up shared environmental factors by comparing their performance between unrelated people to their performance between siblings) and “cross-ancestry accuracy” (improving the accuracy of scores for people outside the European ancestry groups where most of the biobank data is concentrated). The representative explained that pricing varies by customer and the number of embryos tested, but it can reach $50,000.

When it comes to traits that Jonathan Anomaly believes are genetically encoded, intelligence is just the tip of the iceberg. He has also spoken about the heritability of empathy, violence, religiosity, and political leanings.

Herasight tests for just one non-disease-related trait: intelligence. For a couple who produce 10 embryos, it claims it can detect an IQ spread of about 15 points, from the lowest-scoring embryo to the highest. The representative says the company plans to release a detailed white paper on its IQ predictor in the future.

The day of Herasight’s launch, Musk responded to the company announcement: “Cool.” Meanwhile, a Danish researcher named Emil Kirkegaard, whose research has largely focused on IQ differences between racial groups, boosted the company to his nearly 45,000 followers on X (as well as in a Substack blog), writing, “Proper embryo selection just landed.” Kirkegaard has in fact supported Anomaly’s work for years; he’s posted about him on X and recommended his 2020 book Creating Future People, which he called a “biotech eugenics advocacy book,” adding: “Naturally, I agree with this stuff!”

When it comes to traits that Anomaly believes are genetically encoded, intelligence—which he claimed in his talk is about 75% heritable—is just the tip of the iceberg. He has also spoken about the heritability of empathy, impulse control, violence, passivity, religiosity, and political leanings.

Anomaly concedes there are limitations to the kinds of relative predictions that can be made from a small batch of embryos. But he believes we’re only at the dawn of what he likes to call the “reproductive revolution.” At his talk, he pointed to a technology currently in development at a handful of startups: in vitro gametogenesis. IVG aims to create sperm or egg cells in a laboratory using adult stem cells, genetically reprogrammed from cells found in a sample of skin or blood. In theory, this process could allow a couple to quickly produce a practically unlimited number of embryos to analyze for preferred traits. Anomaly predicted this technology could be ready to use on humans within eight years.

“I doubt the FDA will allow it immediately. That’s what places like Próspera are for,” he said, referring to the so-called “startup city” in Honduras, where scientists and entrepreneurs can conduct medical experiments free from the kinds of regulatory oversight they’d encounter in the US.

“You might have a moral intuition that this is wrong,” said Anomaly, “but when it’s discovered that elites are doing it privately … the dominoes are going to fall very, very quickly.” The coming “evolutionary arms race,” he claimed, will “change the moral landscape.”

He added that some of those elites are his own customers: “I could already name names, but I won’t do it.”

After Anomaly’s talk was over, I spoke with a young photographer who told me he was hoping to pursue a master’s degree in theology. He came to the event, he told me, to reckon with the ethical implications of playing God. “Technology is sending us toward an Old-to-New-Testament transition moment, where we have to decide what parts of religion still serve us,” he said soberly.

Criticisms of polygenic testing tend to fall into two camps: skepticism about the tests’ effectiveness and concerns about their ethics. “On one hand,” says Turley from the Social Science Genetic Association Consortium, “you have arguments saying ‘This isn’t going to work anyway, and the reason it’s bad is because we’re tricking parents, which would be a problem.’ And on the other hand, they say, ‘Oh, this is going to work so well that it’s going to lead to enormous inequalities in society.’ It’s just funny to see. Sometimes these arguments are being made by the same people.”

One of those people is Sasha Gusev, who runs a quantitative genetics lab at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. A vocal critic of PGT-P for embryo selection, he also often engages in online debates with the far-right accounts promoting race science on X.

Gusev is one of many professionals in his field who believe that because of numerous confounding socioeconomic factors—for example, childhood nutrition, geography, personal networks, and parenting styles—there isn’t much point in trying to trace outcomes like educational attainment back to genetics, particularly not as a way to prove that there’s a genetic basis for IQ.

He adds, “I think there’s a real risk in moving toward a society where you see genetics and ‘genetic endowments’ as the drivers of people’s behavior and as a ceiling on their outcomes and their capabilities.”

Gusev thinks there is real promise for this technology in clinical settings among specific adult populations. For adults identified as having high polygenic risk scores for cancer and cardiovascular disease, he argues, a combination of early screening and intervention could be lifesaving. But when it comes to the preimplantation testing currently on the market, he thinks there are significant limitations—and few regulatory measures or long-term validation methods to check the promises companies are making. He fears that giving these services too much attention could backfire.

“These reckless, overpromised, and oftentimes just straight-up manipulative embryo selection applications are a risk for the credibility and the utility of these clinical tools,” he says.

Many IVF patients have also had strong reactions to publicity around PGT-P. When the New York Times published an opinion piece about Orchid in the spring, angry parents took to Reddit to rant. One user posted, “For people who dont [sic] know why other types of testing are necessary or needed this just makes IVF people sound like we want to create ‘perfect’ babies, while we just want (our) healthy babies.”

Still, others defended the need for a conversation. “When could technologies like this change the mission from helping infertile people have healthy babies to eugenics?” one Redditor posted. “It’s a fine line to walk and an important discussion to have.”

Some PGT-P proponents, like Kirkegaard and Anomaly, have argued that policy decisions should more explicitly account for genetic differences. In a series of blog posts following the 2024 presidential election, under the header “Make science great again,” Kirkegaard called for ending affirmative action laws, legalizing race-based hiring discrimination, and removing restrictions on data sets like the NIH’s All of Us biobank that prevent researchers like him from using the data for race science. Anomaly has criticized social welfare policies for putting a finger on the scale to “punish the high-IQ people.”

Indeed, the notion of genetic determinism has gained some traction among loyalists to President Donald Trump.

In October 2024, Trump himself made a campaign stop on the conservative radio program The Hugh Hewitt Show. He began a rambling answer about immigration and homicide statistics. “A murderer, I believe this, it’s in their genes. And we got a lot of bad genes in our country right now,” he told the host.

Gusev believes that while embryo selection won’t have much impact on individual outcomes, the intellectual framework endorsed by many PGT-P advocates could have dire social consequences.

“If you just think of the differences that we observe in society as being cultural, then you help people out. You give them better schooling, you give them better nutrition and education, and they’re able to excel,” he says. “If you think of these differences as being strongly innate, then you can fool yourself into thinking that there’s nothing that can be done and people just are what they are at birth.”

For the time being, there are no plans for longitudinal studies to track actual outcomes for the humans these companies have helped bring into the world. Harden, the behavioral geneticist from UT Austin, suspects that 25 years down the line, adults who were once embryos selected on the basis of polygenic risk scores are “going to end up with the same question that we all have.” They will look at their life and wonder, “What would’ve had to change for it to be different?”

Julia Black is a Brooklyn-based features writer and a reporter in residence at Omidyar Network. She has previously worked for Business Insider, Vox, The Information, and Esquire.