Your Gateway to Power, Energy, Datacenters, Bitcoin and AI

Dive into the latest industry updates, our exclusive Paperboy Newsletter, and curated insights designed to keep you informed. Stay ahead with minimal time spent.

Discover What Matters Most to You

AI

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry.

Bitcoin:

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry.

Datacenter:

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry.

Energy:

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry.

Discover What Matter Most to You

Featured Articles

Policy Shock: Big Tech Told to Power Its Own AI Buildout

The AI data center boom has been colliding with grid reality for more than two years. This week, the issue moved closer to the policy front lines. The White House is advancing a “ratepayer protection” framework that has gained visibility in recent days, aimed at ensuring large AI data center projects do not shift grid upgrade costs onto residential customers. It’s a signal widely interpreted by industry observers as encouraging hyperscalers to bring dedicated power solutions to the table. The Power Question Moves to Center Stage Washington now appears poised to push the industry toward a structural response to the data center power conundrum. The new federal impetus for major technology companies to shoulder the cost of their own power infrastructure is quickly emerging as one of the most consequential policy developments for the digital infrastructure sector in 2026. If formalized, the initiative would effectively codify a shift already underway which has found hyperscale and AI developers moving aggressively toward behind-the-meter generation and dedicated energy strategies. For an industry already grappling with interconnection delays, utility pushback, and mounting community scrutiny, the signal is unmistakable. The era of relying primarily on shared grid capacity for large AI campuses may be ending. From Market Trend to Policy Direction Large tech firms, including the biggest cloud and AI players, have been under increasing pressure from regulators and utilities concerned about ratepayer exposure and grid reliability. Policymakers are now signaling that future large-load approvals may hinge on whether developers can demonstrate energy self-sufficiency or dedicated supply. The logic is straightforward. AI campuses are arriving at hundreds of megawatts to gigawatt scale. Transmission upgrades are measured in multi-year timelines. Utilities face growing political pressure to protect residential customers. In that context, the emerging federal posture does not create a new trend so much as accelerate

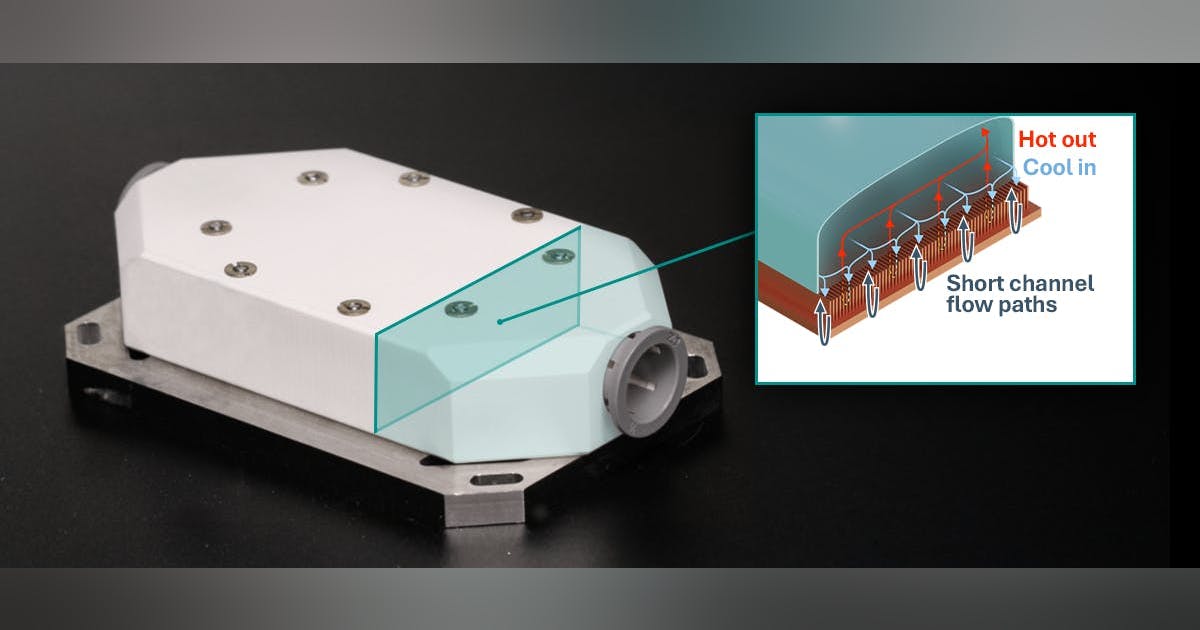

Cooling’s New Reality: It’s Not Air vs. Liquid Anymore. It’s Architecture.

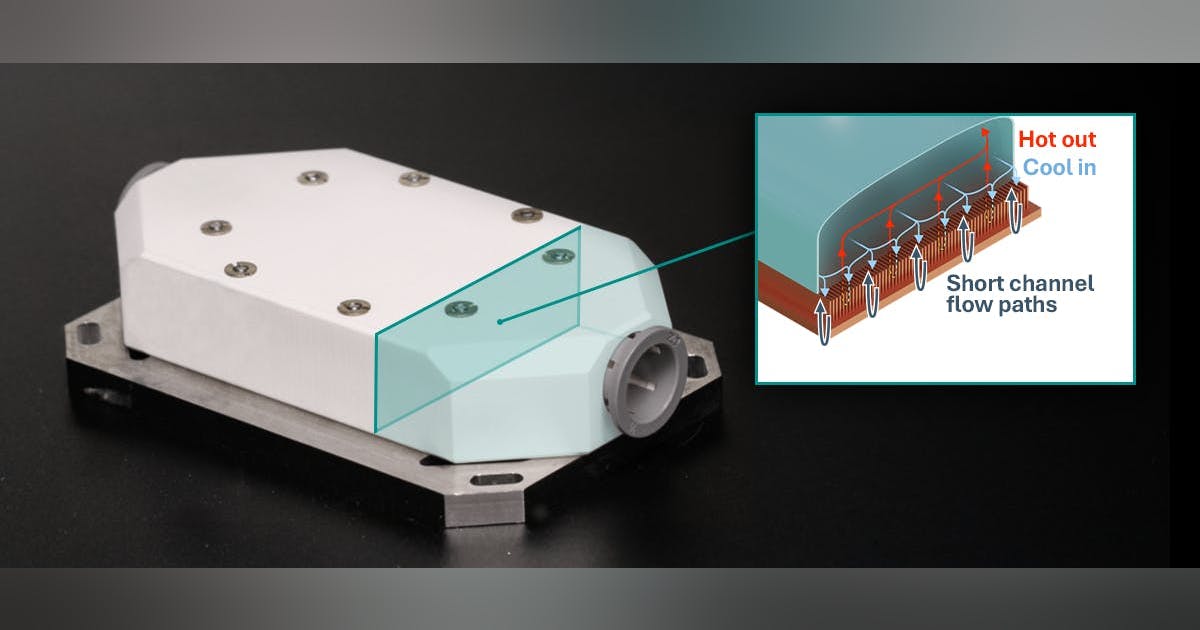

By early 2026, the data center cooling conversation has started to sound less like a product catalog and more like a systems engineering summit. The old framing – air cooling versus liquid cooling – still matters, but it increasingly misses the point. AI-era facilities are being defined by thermal constraints that run from chip-level cold plates to facility heat rejection, with critical decisions now shaped by pumping power, fluid selection, reliability under ambient extremes, water availability, and manufacturing throughput. That full-stack shift is written all over a grab bag of recent cooling announcements. On one end of the spectrum we see a Department of Energy-funded breakthrough aimed directly at next-generation GPU heat flux. On the other, it’s OEM product launches built to withstand –20°F to 140°F operating conditions and recover full cooling capacity within minutes of a power interruption. In between we find a major acquisition move for advanced liquid cooling IP, a manufacturing expansion that more than doubles footprint, and the quiet rise of refrigerants and heat-transfer fluids as design-level considerations. What’s emerging is a new reality. Cooling is becoming one of the primary constraints on AI deployment technically, economically, and geographically. The winners will be the players that can integrate the whole stack and scale it. 1) The Chip-level Arms Race: Single-phase Fights for More Runway The most “pure engineering” signal in this news batch comes from HRL Laboratories, which on Feb. 24, 2026 unveiled details of a single-phase direct liquid cooling approach called Low-Chill™. HRL’s framing is pointed: the industry wants higher GPU and rack power densities, but many operators are wary of the cost and operational complexity of two-phase cooling. HRL says Low-Chill was developed under the U.S. Department of Energy’s ARPA-E COOLERCHIPS program, and claims a leap that goes straight at the bottleneck. It can increase

Aeroderivative Turbines Move to the Center of AI Data Center Power Strategy

From “Backup” to “Bridging” to Behind-the-Meter Power Plants The most important shift is conceptual: these systems are increasingly blurring the boundary between emergency backup and primary power supply. Traditionally, data center electrical architecture has been clearly tiered: UPS (seconds to minutes) to ride through utility disturbances and generator start. Diesel gensets (minutes to hours or days) for extended outages. Utility grid as the primary power source. What’s changing is the rise of bridging power: generation deployed to energize a site before the permanent grid connection is ready, or before sufficient utility capacity becomes available. Providers such as APR Energy now explicitly market turbine-based solutions to data centers seeking behind-the-meter capacity while awaiting utility build-out. That framing matters because it fundamentally changes expected runtime. A generator that operates for a few hours per year is one regulatory category. A turbine that runs continuously for weeks or months while a campus ramps is something very different; and it is drawing increased scrutiny from regulators who are beginning to treat these installations as material generation assets rather than temporary backup systems. The near-term driver is straightforward. AI workloads are arriving faster than grid infrastructure can keep pace. Data Center Frontier and other industry observers have documented the growing scramble for onsite generation as interconnection queues lengthen and critical equipment lead times expand. Mainstream financial and business media have taken notice. The Financial Times has reported on data centers turning to aeroderivative turbines and diesel fleets to bypass multi-year power delays. Reuters has likewise covered large gas-turbine-centric strategies tied to hyperscale campuses, underscoring how quickly the co-located generation model is moving into the mainstream. At the same time, demand pressure is tightening turbine supply chains. Industry reporting points to extended waits for new units, one reason repurposed engine cores and mobile aeroderivative packages are gaining

7×24 Exchange’s Dennis Cronin on the Data Center Workforce Crisis: The Talent Cliff Is Already Here

The data center industry has spent the past two years obsessing over power constraints, AI density, and supply chain pressure. But according to longtime mission critical leader Dennis Cronin, the sector’s most consequential bottleneck may be far more human. In a recent episode of the Data Center Frontier Show Podcast, Cronin — a founding member of 7×24 Exchange International and board member of the Mission Critical Global Alliance (MCGA) — delivered a stark message: the workforce “talent cliff” the industry keeps discussing as a future risk is already impacting operations today. A Million-Job Gap Emerging Cronin’s assessment reframes the workforce conversation from a routine labor shortage to what he describes as a structural and demographic challenge. Based on recent analysis of open roles, he estimates the industry is currently short between 467,000 and 498,000 workers across core operational positions including facilities managers, operations engineers, electricians, generator technicians, and HVAC specialists. Layer in emerging roles tied to AI infrastructure, sustainability, and cyber-physical security, and the potential demand rises to roughly one million jobs. “The coming talent cliff is not coming,” Cronin said. “It’s here, here and now.” With data center capacity expanding at roughly 30% annually, the workforce pipeline is not keeping pace with physical buildout. The Five-Year Experience Trap One of the industry’s most persistent self-inflicted wounds, Cronin argues, is the widespread requirement for five years of experience in roles that are effectively entry level. The result is a closed-loop hiring dynamic: New workers can’t get hired without experience They can’t gain experience without being hired Operators end up poaching from each other Workers may benefit from the resulting 10–20% salary jumps, but the overall talent pool remains stagnant. “It’s not helping us grow the industry,” Cronin said. In a market defined by rapid expansion and increasing system complexity, that

JLL: Hyperscale and AI Demand Push North American Data Centers Toward Industrial Scale

JLL’s North America Data Center Report Year-End 2025 makes a clear argument that the sector is no longer merely expanding but has shifted into a phase of industrial-scale acceleration driven by hyperscalers, AI platforms, and capital markets that increasingly treat digital infrastructure as core, bond-like collateral. The report’s central thesis is straightforward. Structural demand has overwhelmed traditional real estate cycles. JLL supports that claim with a set of reinforcing signals: Vacancy remains pinned near zero. Most new supply is pre-leased years ahead. Rents continue to climb. Debt markets remain highly liquid. Investors are engineering new financial structures to sustain growth. Author Andrew Batson notes that JLL’s Data Center Solutions team significantly expanded its methodology for this edition, incorporating substantially more hyperscale and owner-occupied capacity along with more than 40 additional markets. The subtitle — “The data center sector shifts into hyperdrive” — serves as an apt one-line summary of the report’s posture. The methodological change is not cosmetic. By incorporating hyper-owned infrastructure, total market size increases, vacancy compresses, and historical time series shift accordingly. JLL is explicit that these revisions reflect improved visibility into the market rather than a change in underlying fundamentals; and, if anything, suggest prior reports understated the sector’s true scale. The Market in Three Words: Tight, Pre-Leased, Relentless The report’s key highlights page serves as an executive brief for investors, offering a concise snapshot of market conditions that remain historically constrained. Vacancy stands at just 1%, unchanged year over year, while 92% of capacity currently under construction is already pre-leased. At the same time, geographic diversification continues to accelerate, with 64% of new builds now occurring in so-called frontier markets. JLL also notes that Texas, when viewed as a unified market, could surpass Northern Virginia as the top data center market by 2030, even as capital

Glenfarne signs LOI with TotalEnergies for Alaska LNG offtake

“The Alaska LNG project is indeed very well geographically positioned to better serve our Asian customers,” said Patrick Pouyanné, chairman and chief executive officer of TotalEnergies. He said the agreement “illustrates TotalEnergies’ ambition to consolidate its position as a leading buyer of US LNG, while diversifying its supply sources.” The company was the number one exporter of US LNG in 2025 with 19 million tonnes representing 18% of US production, Pouyanné said. Glenfarne intends to contract 80%, or 16 million tpy, of Alaska LNG’s 20-million tpy volume to finance the project and now has 13 million tpy accounted for under preliminary long-term agreements with Total Energies, JERA, Tokyo Gas, CPC, PTT, and POSCO. Alaska LNG project works Alaska LNG, on the US Pacific coast, is the only federally authorized LNG export terminal in this region. It plans a total capacity of 20 million tpy, with direct access to Asia. Worley Ltd. completed primary FEED work on the Alaska LNG pipeline at the end of 2025 and has been provisionally named to provide engineering, procurement, and construction management services for the mainline. Alaska LNG has gas sales precedent agreements with North Slope natural gas producers including ExxonMobil, Hilcorp, and Great Bear Pantheon, and letters of intent to sell natural gas to ENSTAR Natural Gas, Alaska’s largest natural gas utility, and Donlin Gold Mine, one of the largest known undeveloped gold deposits in the world. Alaska LNG consists of an 807-mile 42-in. pipeline to deliver natural gas from Alaska’s North Slope to meet Alaska’s domestic needs and produce 20 million tpy of LNG for export. The project is being developed in two phases. Phase one includes the domestic pipeline to deliver natural gas to Alaskans. Phase two will add the infrastructure to export LNG. Glenfarne owns 75% of Alaska LNG and the

Policy Shock: Big Tech Told to Power Its Own AI Buildout

The AI data center boom has been colliding with grid reality for more than two years. This week, the issue moved closer to the policy front lines. The White House is advancing a “ratepayer protection” framework that has gained visibility in recent days, aimed at ensuring large AI data center projects do not shift grid upgrade costs onto residential customers. It’s a signal widely interpreted by industry observers as encouraging hyperscalers to bring dedicated power solutions to the table. The Power Question Moves to Center Stage Washington now appears poised to push the industry toward a structural response to the data center power conundrum. The new federal impetus for major technology companies to shoulder the cost of their own power infrastructure is quickly emerging as one of the most consequential policy developments for the digital infrastructure sector in 2026. If formalized, the initiative would effectively codify a shift already underway which has found hyperscale and AI developers moving aggressively toward behind-the-meter generation and dedicated energy strategies. For an industry already grappling with interconnection delays, utility pushback, and mounting community scrutiny, the signal is unmistakable. The era of relying primarily on shared grid capacity for large AI campuses may be ending. From Market Trend to Policy Direction Large tech firms, including the biggest cloud and AI players, have been under increasing pressure from regulators and utilities concerned about ratepayer exposure and grid reliability. Policymakers are now signaling that future large-load approvals may hinge on whether developers can demonstrate energy self-sufficiency or dedicated supply. The logic is straightforward. AI campuses are arriving at hundreds of megawatts to gigawatt scale. Transmission upgrades are measured in multi-year timelines. Utilities face growing political pressure to protect residential customers. In that context, the emerging federal posture does not create a new trend so much as accelerate

Cooling’s New Reality: It’s Not Air vs. Liquid Anymore. It’s Architecture.

By early 2026, the data center cooling conversation has started to sound less like a product catalog and more like a systems engineering summit. The old framing – air cooling versus liquid cooling – still matters, but it increasingly misses the point. AI-era facilities are being defined by thermal constraints that run from chip-level cold plates to facility heat rejection, with critical decisions now shaped by pumping power, fluid selection, reliability under ambient extremes, water availability, and manufacturing throughput. That full-stack shift is written all over a grab bag of recent cooling announcements. On one end of the spectrum we see a Department of Energy-funded breakthrough aimed directly at next-generation GPU heat flux. On the other, it’s OEM product launches built to withstand –20°F to 140°F operating conditions and recover full cooling capacity within minutes of a power interruption. In between we find a major acquisition move for advanced liquid cooling IP, a manufacturing expansion that more than doubles footprint, and the quiet rise of refrigerants and heat-transfer fluids as design-level considerations. What’s emerging is a new reality. Cooling is becoming one of the primary constraints on AI deployment technically, economically, and geographically. The winners will be the players that can integrate the whole stack and scale it. 1) The Chip-level Arms Race: Single-phase Fights for More Runway The most “pure engineering” signal in this news batch comes from HRL Laboratories, which on Feb. 24, 2026 unveiled details of a single-phase direct liquid cooling approach called Low-Chill™. HRL’s framing is pointed: the industry wants higher GPU and rack power densities, but many operators are wary of the cost and operational complexity of two-phase cooling. HRL says Low-Chill was developed under the U.S. Department of Energy’s ARPA-E COOLERCHIPS program, and claims a leap that goes straight at the bottleneck. It can increase

Aeroderivative Turbines Move to the Center of AI Data Center Power Strategy

From “Backup” to “Bridging” to Behind-the-Meter Power Plants The most important shift is conceptual: these systems are increasingly blurring the boundary between emergency backup and primary power supply. Traditionally, data center electrical architecture has been clearly tiered: UPS (seconds to minutes) to ride through utility disturbances and generator start. Diesel gensets (minutes to hours or days) for extended outages. Utility grid as the primary power source. What’s changing is the rise of bridging power: generation deployed to energize a site before the permanent grid connection is ready, or before sufficient utility capacity becomes available. Providers such as APR Energy now explicitly market turbine-based solutions to data centers seeking behind-the-meter capacity while awaiting utility build-out. That framing matters because it fundamentally changes expected runtime. A generator that operates for a few hours per year is one regulatory category. A turbine that runs continuously for weeks or months while a campus ramps is something very different; and it is drawing increased scrutiny from regulators who are beginning to treat these installations as material generation assets rather than temporary backup systems. The near-term driver is straightforward. AI workloads are arriving faster than grid infrastructure can keep pace. Data Center Frontier and other industry observers have documented the growing scramble for onsite generation as interconnection queues lengthen and critical equipment lead times expand. Mainstream financial and business media have taken notice. The Financial Times has reported on data centers turning to aeroderivative turbines and diesel fleets to bypass multi-year power delays. Reuters has likewise covered large gas-turbine-centric strategies tied to hyperscale campuses, underscoring how quickly the co-located generation model is moving into the mainstream. At the same time, demand pressure is tightening turbine supply chains. Industry reporting points to extended waits for new units, one reason repurposed engine cores and mobile aeroderivative packages are gaining

7×24 Exchange’s Dennis Cronin on the Data Center Workforce Crisis: The Talent Cliff Is Already Here

The data center industry has spent the past two years obsessing over power constraints, AI density, and supply chain pressure. But according to longtime mission critical leader Dennis Cronin, the sector’s most consequential bottleneck may be far more human. In a recent episode of the Data Center Frontier Show Podcast, Cronin — a founding member of 7×24 Exchange International and board member of the Mission Critical Global Alliance (MCGA) — delivered a stark message: the workforce “talent cliff” the industry keeps discussing as a future risk is already impacting operations today. A Million-Job Gap Emerging Cronin’s assessment reframes the workforce conversation from a routine labor shortage to what he describes as a structural and demographic challenge. Based on recent analysis of open roles, he estimates the industry is currently short between 467,000 and 498,000 workers across core operational positions including facilities managers, operations engineers, electricians, generator technicians, and HVAC specialists. Layer in emerging roles tied to AI infrastructure, sustainability, and cyber-physical security, and the potential demand rises to roughly one million jobs. “The coming talent cliff is not coming,” Cronin said. “It’s here, here and now.” With data center capacity expanding at roughly 30% annually, the workforce pipeline is not keeping pace with physical buildout. The Five-Year Experience Trap One of the industry’s most persistent self-inflicted wounds, Cronin argues, is the widespread requirement for five years of experience in roles that are effectively entry level. The result is a closed-loop hiring dynamic: New workers can’t get hired without experience They can’t gain experience without being hired Operators end up poaching from each other Workers may benefit from the resulting 10–20% salary jumps, but the overall talent pool remains stagnant. “It’s not helping us grow the industry,” Cronin said. In a market defined by rapid expansion and increasing system complexity, that

JLL: Hyperscale and AI Demand Push North American Data Centers Toward Industrial Scale

JLL’s North America Data Center Report Year-End 2025 makes a clear argument that the sector is no longer merely expanding but has shifted into a phase of industrial-scale acceleration driven by hyperscalers, AI platforms, and capital markets that increasingly treat digital infrastructure as core, bond-like collateral. The report’s central thesis is straightforward. Structural demand has overwhelmed traditional real estate cycles. JLL supports that claim with a set of reinforcing signals: Vacancy remains pinned near zero. Most new supply is pre-leased years ahead. Rents continue to climb. Debt markets remain highly liquid. Investors are engineering new financial structures to sustain growth. Author Andrew Batson notes that JLL’s Data Center Solutions team significantly expanded its methodology for this edition, incorporating substantially more hyperscale and owner-occupied capacity along with more than 40 additional markets. The subtitle — “The data center sector shifts into hyperdrive” — serves as an apt one-line summary of the report’s posture. The methodological change is not cosmetic. By incorporating hyper-owned infrastructure, total market size increases, vacancy compresses, and historical time series shift accordingly. JLL is explicit that these revisions reflect improved visibility into the market rather than a change in underlying fundamentals; and, if anything, suggest prior reports understated the sector’s true scale. The Market in Three Words: Tight, Pre-Leased, Relentless The report’s key highlights page serves as an executive brief for investors, offering a concise snapshot of market conditions that remain historically constrained. Vacancy stands at just 1%, unchanged year over year, while 92% of capacity currently under construction is already pre-leased. At the same time, geographic diversification continues to accelerate, with 64% of new builds now occurring in so-called frontier markets. JLL also notes that Texas, when viewed as a unified market, could surpass Northern Virginia as the top data center market by 2030, even as capital

Glenfarne signs LOI with TotalEnergies for Alaska LNG offtake

“The Alaska LNG project is indeed very well geographically positioned to better serve our Asian customers,” said Patrick Pouyanné, chairman and chief executive officer of TotalEnergies. He said the agreement “illustrates TotalEnergies’ ambition to consolidate its position as a leading buyer of US LNG, while diversifying its supply sources.” The company was the number one exporter of US LNG in 2025 with 19 million tonnes representing 18% of US production, Pouyanné said. Glenfarne intends to contract 80%, or 16 million tpy, of Alaska LNG’s 20-million tpy volume to finance the project and now has 13 million tpy accounted for under preliminary long-term agreements with Total Energies, JERA, Tokyo Gas, CPC, PTT, and POSCO. Alaska LNG project works Alaska LNG, on the US Pacific coast, is the only federally authorized LNG export terminal in this region. It plans a total capacity of 20 million tpy, with direct access to Asia. Worley Ltd. completed primary FEED work on the Alaska LNG pipeline at the end of 2025 and has been provisionally named to provide engineering, procurement, and construction management services for the mainline. Alaska LNG has gas sales precedent agreements with North Slope natural gas producers including ExxonMobil, Hilcorp, and Great Bear Pantheon, and letters of intent to sell natural gas to ENSTAR Natural Gas, Alaska’s largest natural gas utility, and Donlin Gold Mine, one of the largest known undeveloped gold deposits in the world. Alaska LNG consists of an 807-mile 42-in. pipeline to deliver natural gas from Alaska’s North Slope to meet Alaska’s domestic needs and produce 20 million tpy of LNG for export. The project is being developed in two phases. Phase one includes the domestic pipeline to deliver natural gas to Alaskans. Phase two will add the infrastructure to export LNG. Glenfarne owns 75% of Alaska LNG and the

Equinor lets EPC contract for Gullfaks field

@import url(‘https://fonts.googleapis.com/css2?family=Inter:[email protected]&display=swap’); a { color: var(–color-primary-main); } .ebm-page__main h1, .ebm-page__main h2, .ebm-page__main h3, .ebm-page__main h4, .ebm-page__main h5, .ebm-page__main h6 { font-family: Inter; } body { line-height: 150%; letter-spacing: 0.025em; font-family: Inter; } button, .ebm-button-wrapper { font-family: Inter; } .label-style { text-transform: uppercase; color: var(–color-grey); font-weight: 600; font-size: 0.75rem; } .caption-style { font-size: 0.75rem; opacity: .6; } #onetrust-pc-sdk [id*=btn-handler], #onetrust-pc-sdk [class*=btn-handler] { background-color: #c19a06 !important; border-color: #c19a06 !important; } #onetrust-policy a, #onetrust-pc-sdk a, #ot-pc-content a { color: #c19a06 !important; } #onetrust-consent-sdk #onetrust-pc-sdk .ot-active-menu { border-color: #c19a06 !important; } #onetrust-consent-sdk #onetrust-accept-btn-handler, #onetrust-banner-sdk #onetrust-reject-all-handler, #onetrust-consent-sdk #onetrust-pc-btn-handler.cookie-setting-link { background-color: #c19a06 !important; border-color: #c19a06 !important; } #onetrust-consent-sdk .onetrust-pc-btn-handler { color: #c19a06 !important; border-color: #c19a06 !important; } Equinor Energy AS has let an engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) contract to SLB to upgrade the subsea compression system for Gullfaks field in the Norwegian North Sea. Under the contract, SLB OneSubsea will deliver two next-generation compressor modules to replace the units originally supplied in 2015 as part of the world’s first multiphase subsea compression system. The upgraded modules will increase differential pressure and flow capacity, enhancing recovery and extending field life, SLB said, while installation within the existing subsea infrastructure will minimize downtime and reduce overall campaign costs, the company continued. Gullfaks field lies in block 34/10 in the northern part of the North Sea. Three large production platforms with concrete substructures make up the development solution for the main field.

Oxy cutting oil-and-gas capex by $300 million, eyes 1% production growth

@import url(‘https://fonts.googleapis.com/css2?family=Inter:[email protected]&display=swap’); a { color: var(–color-primary-main); } .ebm-page__main h1, .ebm-page__main h2, .ebm-page__main h3, .ebm-page__main h4, .ebm-page__main h5, .ebm-page__main h6 { font-family: Inter; } body { line-height: 150%; letter-spacing: 0.025em; font-family: Inter; } button, .ebm-button-wrapper { font-family: Inter; } .label-style { text-transform: uppercase; color: var(–color-grey); font-weight: 600; font-size: 0.75rem; } .caption-style { font-size: 0.75rem; opacity: .6; } #onetrust-pc-sdk [id*=btn-handler], #onetrust-pc-sdk [class*=btn-handler] { background-color: #c19a06 !important; border-color: #c19a06 !important; } #onetrust-policy a, #onetrust-pc-sdk a, #ot-pc-content a { color: #c19a06 !important; } #onetrust-consent-sdk #onetrust-pc-sdk .ot-active-menu { border-color: #c19a06 !important; } #onetrust-consent-sdk #onetrust-accept-btn-handler, #onetrust-banner-sdk #onetrust-reject-all-handler, #onetrust-consent-sdk #onetrust-pc-btn-handler.cookie-setting-link { background-color: #c19a06 !important; border-color: #c19a06 !important; } #onetrust-consent-sdk .onetrust-pc-btn-handler { color: #c19a06 !important; border-color: #c19a06 !important; } Occidental Petroleum Corp., Houston, will spend $5.5-5.9 billion on capital projects this year, an 8% drop from 2025 and $800 million less than executives’ early forecast late last year, as the company continues to emphasize efficiency gains. Spending on oil-and-gas operations will be $300 million less than last year. Sunil Mathew, chief financial officer, late last week told investors and analysts that Occidental’s capital spending budget for 2026 (adjusted for the recently completed divestiture of OxyChem) will focus on short-cycle projects and be roughly 70% devoted to US onshore assets. Still, onshore capex will drop by $400 million from last year in part because of a drop in Permian basin activities and efficiency improvements. Other elements of Occidental’s spending plan include: A reduction of about $100 million compared to last year for exploration work A $250 million drop in spending at the company’s Low Carbon Ventures group housing Stratos Mathew said capex, which will be weighted a little to the first half, sets up Occidental’s production to average 1.45 MMboe/d for the full year, a tick up from 2025’s average of 1.434 MMboe/d but down from the roughly 1.48

Diamondback’s Van’t Hof growing ‘more confident about the macro’

The early Barnett production will help Diamondback slightly increase its oil production this year from 2025’s average of 497,200 b/d. Van’t Hof and his team are eyeing 505,000 b/d this year with total expected production of 926,000-962,000 boe/d versus last year’s 921,000 boe/d. On a Feb. 24 conference call with analysts and investors, Van’t Hof said he’s feeling better than in recent quarters about that production number possibly moving up. The bigger picture for the oil-and-gas sector, he said, has grown a bit brighter. “Some people have been talking about [oversupplying the market] for 2 years. It just hasn’t seemed to happen as aggressively as some expected,” Van’t Hof said. “As we turn to higher demand in the summer and driving season […] people will start to find reasons to be less bearish […] In general, we just feel more confident about the macro after a couple of big shocks last year on the supply side and the demand side.” In the last 3 months of 2025, Diamondback posted a net loss of more than $1.4 billion due to a $3.6 billion impairment charge because of lower commodity prices’ effect on the company’s reserves. Adjusted EBITA fell to $2.0 billion from $2.5 billion in late 2024 and revenues during the quarter slipped to nearly $3.4 billion from $3.7 billion. Shares of Diamondback (Ticker: FANG) were essentially flat at $173.68 in early-afternoon trading on Feb. 24. Over the past 6 months, they are still up more than 20% and the company’s market value is now $50 billion.

Vaalco Energy advances offshore drilling, development in Gabon and Ivory Coast

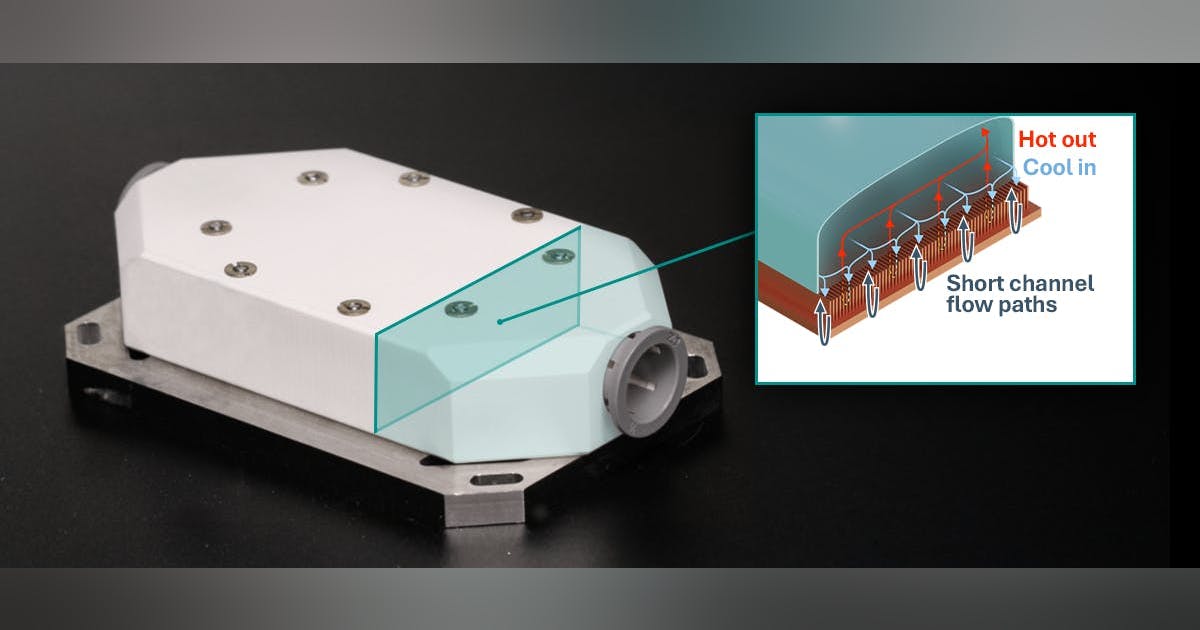

Vaalco Energy Inc. is drilling Etame field offshore Gabon and a preparing a field development plan (FDP) off Ivory Coast. In Gabon, Vaalco drilled, completed, and placed Etame 15H-ST development well on production in Etame oil field in 1V block. The well has a 250 m lateral interval of net pay in high-quality Gamba sands near the top of the reservoir. The well had a stabilized flow rate of about 2,000 gross b/d of oil with a 38% water cut through a 42/64-in. choke and ESP at 54 Hz, confirming expectations from the ET-15P pilot well results. The company is working to stabilize pressure and manage the reservoir. West Etame step out exploration well spudded in mid-February. Drilling the well from the S1 slot on the Etame platform Etame West (ET-14P) exploration prospect has a 57% chance of geologic success and is expected to reach the target zone by mid-March. Etame Marin block lies in Congo basin about 32 km off the coast of Gabon. The license area is spread over five fields covering about 187 sq km. Vaalco is operator at the block with 58.8% interest. In Ivory Coast, Vaalco has been confirmed as operator (60%) of Kossipo field on the CI-40 Block southwest of Baobab field with partner PetroCI holding the remaining 40%. An FDP is expected to be completed in second-half 2026. New ocean bottom node (OBN) seismic data is expected to drive and derisk Vaalco’s updated evaluation and development plan. Estimated Gross 2C resources are 102-293 MMboe in place. The Baobab Ivorien (formerly MV10) floating production storage and offloading vessel (FPSO) is currently off the East coast of Africa and is expected to return to Ivory Coast by late March.

Ovintiv sets 2026 plan around Permian, Montney after declaring portfolio shift ‘complete’

2026 guidance For 2026, Ovintiv plans to invest $2.25–2.35 billion, up slightly from the $2.147 billion spent in 2025. McCracken said capital spend will be highest in first-quarter 2026 at about $625 million, “largely due to $50 million of capital allocated to the Anadarko and some drilling activity in the Montney that we inherited from NuVista.” The program is designed to deliver 205,000–212,000 b/d of oil and condensate, some 2 bcfd of natural gas, and 620,000–645,000 boe/d total company production. For full-year 2025, the company produced 614,500 boe/d. The company is pursuing a “stay‑flat” oil strategy, maintaining liquids output through steady activity rather than aggressive volume growth. Permian Ovintiv plans to run 5 rigs and 1-2 frac crews in the Permian basin this year, bringing 125–135 net wells online. Oil and condensate volumes are expected to average 117,000–123,000 b/d, with natural gas production of 270–295 MMcfd. The company projects 2026 drilling and completion costs below $600/ft, about $25/ft lower than 2025. Chief operating officer Gregory Givens credited faster cycle times and ongoing application of surfactant technology. Ovintiv has now deployed surfactants in about 300 Permian wells, generating a 9% uplift in oil productivity versus comparable control wells. Givens also reiterated that Ovintiv remains committed to its established cube‑development model. Responding to an analyst question, he said the company continues completing entire cubes at once, then returning “18 months later” to develop adjacent cubes—an approach that stabilizes well performance and reduces parent‑child degradation, he said. “We are getting the whole cube at the same time, and that is working quite well for us,” he said. The company plans to drill its first Barnett Woodford test well across Midland basin acreage in 2026. Ovintiv holds Barnett rights across roughly 100,000 acres and intends to move cautiously given the zone’s depth, higher pressure,

Interior trims environmental reviews to speed project development

The US DOI issued a final rule to reform NEPA, aiming to speed up energy project approvals on federal lands by reducing procedural delays and clarifying review processes, despite criticism from environmental groups. Feb. 24, 2026 2 min read Key Highlights The final rule streamlines environmental review processes for energy projects on federal lands, aiming to reduce approval times. It clarifies roles for federal, state, local, and tribal agencies, including procedures for public comments on significant projects. Environmental groups and Democratic attorneys general have challenged the rule, citing concerns over diminished public participation and environmental protections. Interior Secretary Doug Burgum emphasizes that the reforms restore NEPA to its original purpose of informing decisions without unnecessary delays. The rule adopts over 80% of provisions from the draft NEPA reform.

Microsoft will invest $80B in AI data centers in fiscal 2025

And Microsoft isn’t the only one that is ramping up its investments into AI-enabled data centers. Rival cloud service providers are all investing in either upgrading or opening new data centers to capture a larger chunk of business from developers and users of large language models (LLMs). In a report published in October 2024, Bloomberg Intelligence estimated that demand for generative AI would push Microsoft, AWS, Google, Oracle, Meta, and Apple would between them devote $200 billion to capex in 2025, up from $110 billion in 2023. Microsoft is one of the biggest spenders, followed closely by Google and AWS, Bloomberg Intelligence said. Its estimate of Microsoft’s capital spending on AI, at $62.4 billion for calendar 2025, is lower than Smith’s claim that the company will invest $80 billion in the fiscal year to June 30, 2025. Both figures, though, are way higher than Microsoft’s 2020 capital expenditure of “just” $17.6 billion. The majority of the increased spending is tied to cloud services and the expansion of AI infrastructure needed to provide compute capacity for OpenAI workloads. Separately, last October Amazon CEO Andy Jassy said his company planned total capex spend of $75 billion in 2024 and even more in 2025, with much of it going to AWS, its cloud computing division.

John Deere unveils more autonomous farm machines to address skill labor shortage

Join our daily and weekly newsletters for the latest updates and exclusive content on industry-leading AI coverage. Learn More Self-driving tractors might be the path to self-driving cars. John Deere has revealed a new line of autonomous machines and tech across agriculture, construction and commercial landscaping. The Moline, Illinois-based John Deere has been in business for 187 years, yet it’s been a regular as a non-tech company showing off technology at the big tech trade show in Las Vegas and is back at CES 2025 with more autonomous tractors and other vehicles. This is not something we usually cover, but John Deere has a lot of data that is interesting in the big picture of tech. The message from the company is that there aren’t enough skilled farm laborers to do the work that its customers need. It’s been a challenge for most of the last two decades, said Jahmy Hindman, CTO at John Deere, in a briefing. Much of the tech will come this fall and after that. He noted that the average farmer in the U.S. is over 58 and works 12 to 18 hours a day to grow food for us. And he said the American Farm Bureau Federation estimates there are roughly 2.4 million farm jobs that need to be filled annually; and the agricultural work force continues to shrink. (This is my hint to the anti-immigration crowd). John Deere’s autonomous 9RX Tractor. Farmers can oversee it using an app. While each of these industries experiences their own set of challenges, a commonality across all is skilled labor availability. In construction, about 80% percent of contractors struggle to find skilled labor. And in commercial landscaping, 86% of landscaping business owners can’t find labor to fill open positions, he said. “They have to figure out how to do

2025 playbook for enterprise AI success, from agents to evals

Join our daily and weekly newsletters for the latest updates and exclusive content on industry-leading AI coverage. Learn More 2025 is poised to be a pivotal year for enterprise AI. The past year has seen rapid innovation, and this year will see the same. This has made it more critical than ever to revisit your AI strategy to stay competitive and create value for your customers. From scaling AI agents to optimizing costs, here are the five critical areas enterprises should prioritize for their AI strategy this year. 1. Agents: the next generation of automation AI agents are no longer theoretical. In 2025, they’re indispensable tools for enterprises looking to streamline operations and enhance customer interactions. Unlike traditional software, agents powered by large language models (LLMs) can make nuanced decisions, navigate complex multi-step tasks, and integrate seamlessly with tools and APIs. At the start of 2024, agents were not ready for prime time, making frustrating mistakes like hallucinating URLs. They started getting better as frontier large language models themselves improved. “Let me put it this way,” said Sam Witteveen, cofounder of Red Dragon, a company that develops agents for companies, and that recently reviewed the 48 agents it built last year. “Interestingly, the ones that we built at the start of the year, a lot of those worked way better at the end of the year just because the models got better.” Witteveen shared this in the video podcast we filmed to discuss these five big trends in detail. Models are getting better and hallucinating less, and they’re also being trained to do agentic tasks. Another feature that the model providers are researching is a way to use the LLM as a judge, and as models get cheaper (something we’ll cover below), companies can use three or more models to

OpenAI’s red teaming innovations define new essentials for security leaders in the AI era

Join our daily and weekly newsletters for the latest updates and exclusive content on industry-leading AI coverage. Learn More OpenAI has taken a more aggressive approach to red teaming than its AI competitors, demonstrating its security teams’ advanced capabilities in two areas: multi-step reinforcement and external red teaming. OpenAI recently released two papers that set a new competitive standard for improving the quality, reliability and safety of AI models in these two techniques and more. The first paper, “OpenAI’s Approach to External Red Teaming for AI Models and Systems,” reports that specialized teams outside the company have proven effective in uncovering vulnerabilities that might otherwise have made it into a released model because in-house testing techniques may have missed them. In the second paper, “Diverse and Effective Red Teaming with Auto-Generated Rewards and Multi-Step Reinforcement Learning,” OpenAI introduces an automated framework that relies on iterative reinforcement learning to generate a broad spectrum of novel, wide-ranging attacks. Going all-in on red teaming pays practical, competitive dividends It’s encouraging to see competitive intensity in red teaming growing among AI companies. When Anthropic released its AI red team guidelines in June of last year, it joined AI providers including Google, Microsoft, Nvidia, OpenAI, and even the U.S.’s National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), which all had released red teaming frameworks. Investing heavily in red teaming yields tangible benefits for security leaders in any organization. OpenAI’s paper on external red teaming provides a detailed analysis of how the company strives to create specialized external teams that include cybersecurity and subject matter experts. The goal is to see if knowledgeable external teams can defeat models’ security perimeters and find gaps in their security, biases and controls that prompt-based testing couldn’t find. What makes OpenAI’s recent papers noteworthy is how well they define using human-in-the-middle

Three Aberdeen oil company headquarters sell for £45m

Three Aberdeen oil company headquarters have been sold in a deal worth £45 million. The CNOOC, Apache and Taqa buildings at the Prime Four business park in Kingswells have been acquired by EEH Ventures. The trio of buildings, totalling 275,000 sq ft, were previously owned by Canadian firm BMO. The financial services powerhouse first bought the buildings in 2014 but took the decision to sell the buildings as part of a “long-standing strategy to reduce their office exposure across the UK”. The deal was the largest to take place throughout Scotland during the last quarter of 2024. Trio of buildings snapped up London headquartered EEH Ventures was founded in 2013 and owns a number of residential, offices, shopping centres and hotels throughout the UK. All three Kingswells-based buildings were pre-let, designed and constructed by Aberdeen property developer Drum in 2012 on a 15-year lease. © Supplied by CBREThe Aberdeen headquarters of Taqa. Image: CBRE The North Sea headquarters of Middle-East oil firm Taqa has previously been described as “an amazing success story in the Granite City”. Taqa announced in 2023 that it intends to cease production from all of its UK North Sea platforms by the end of 2027. Meanwhile, Apache revealed at the end of last year it is planning to exit the North Sea by the end of 2029 blaming the windfall tax. The US firm first entered the North Sea in 2003 but will wrap up all of its UK operations by 2030. Aberdeen big deals The Prime Four acquisition wasn’t the biggest Granite City commercial property sale of 2024. American private equity firm Lone Star bought Union Square shopping centre from Hammerson for £111m. © ShutterstockAberdeen city centre. Hammerson, who also built the property, had originally been seeking £150m. BP’s North Sea headquarters in Stoneywood, Aberdeen, was also sold. Manchester-based

2025 ransomware predictions, trends, and how to prepare

Zscaler ThreatLabz research team has revealed critical insights and predictions on ransomware trends for 2025. The latest Ransomware Report uncovered a surge in sophisticated tactics and extortion attacks. As ransomware remains a key concern for CISOs and CIOs, the report sheds light on actionable strategies to mitigate risks. Top Ransomware Predictions for 2025: ● AI-Powered Social Engineering: In 2025, GenAI will fuel voice phishing (vishing) attacks. With the proliferation of GenAI-based tooling, initial access broker groups will increasingly leverage AI-generated voices; which sound more and more realistic by adopting local accents and dialects to enhance credibility and success rates. ● The Trifecta of Social Engineering Attacks: Vishing, Ransomware and Data Exfiltration. Additionally, sophisticated ransomware groups, like the Dark Angels, will continue the trend of low-volume, high-impact attacks; preferring to focus on an individual company, stealing vast amounts of data without encrypting files, and evading media and law enforcement scrutiny. ● Targeted Industries Under Siege: Manufacturing, healthcare, education, energy will remain primary targets, with no slowdown in attacks expected. ● New SEC Regulations Drive Increased Transparency: 2025 will see an uptick in reported ransomware attacks and payouts due to new, tighter SEC requirements mandating that public companies report material incidents within four business days. ● Ransomware Payouts Are on the Rise: In 2025 ransom demands will most likely increase due to an evolving ecosystem of cybercrime groups, specializing in designated attack tactics, and collaboration by these groups that have entered a sophisticated profit sharing model using Ransomware-as-a-Service. To combat damaging ransomware attacks, Zscaler ThreatLabz recommends the following strategies. ● Fighting AI with AI: As threat actors use AI to identify vulnerabilities, organizations must counter with AI-powered zero trust security systems that detect and mitigate new threats. ● Advantages of adopting a Zero Trust architecture: A Zero Trust cloud security platform stops

MIT Technology Review is a 2026 ASME finalist in reporting

AI is often described as a black box, but it’s not just its inner workings that are mysterious. Leading AI companies have kept figures on energy use closely guarded, making it hard to determine its climate impact. In a rigorous investigation, senior AI reporter James O’Donnell and senior climate reporter Casey Crownhart spent six months digging through hundreds of pages of reports, interviewing experts, and crunching the numbers. The team drilled down into the energy cost of a single prompt, and then zoomed out to build a broader picture illustrating the potential impacts of AI’s current and future energy demand. Their work revealed just how big AI’s energy footprint is, where that energy comes from, and who will pay for it. In the months following the project’s publication, major AI companies including Open AI, Mistral, and Google published details about their models’ energy and water usage. The 2026 awards will be presented in New York City on May 19.

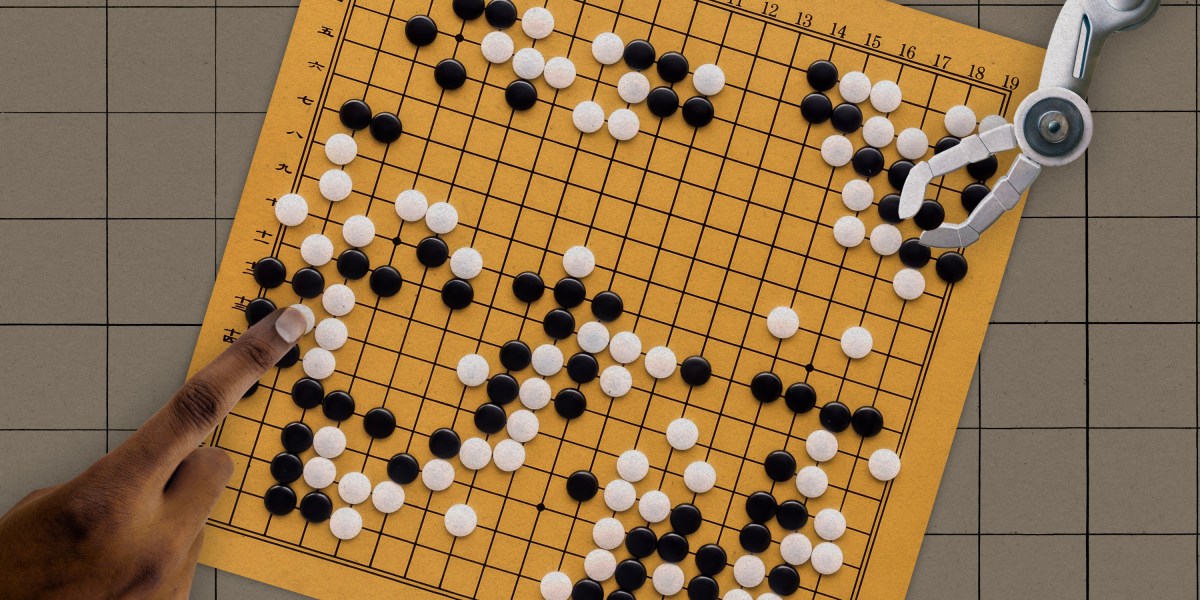

The Download: how AI is shaking up Go, and a cybersecurity mystery

This is today’s edition of The Download, our weekday newsletter that provides a daily dose of what’s going on in the world of technology. AI is rewiring how the world’s best Go players think Ten years ago AlphaGo, Google DeepMind’s AI program, stunned the world by defeating the South Korean Go player Lee Sedol.And in the years since, AI has upended the game. It’s overturned centuries-old principles about the best moves and introduced entirely new ones. Players now train to replicate AI’s moves as closely as they can rather than inventing their own, even when the machine’s thinking remains mysterious to them. Meanwhile, AI is democratizing access to training, and more female players are climbing the ranks as a result.Today, it is essentially impossible to compete professionally without using AI. Some say the technology has drained the game of its creativity, while others think there is still room for human invention. Read the full story. —Michelle Kim

MIT Technology Review Narrated: Hackers made death threats against this security researcher. Big mistake.

In April 2024, a mysterious someone using the online handles “Waifu” and “Judische” began posting death threats on Telegram and Discord channels aimed at a cybersecurity researcher named Allison Nixon.As chief research officer at the cyber investigations firm Unit 221B, Nixon had built a career tracking cybercriminals and helping get them arrested. And although she had taken an interest in the Waifu persona in years past for crimes he boasted about committing, he hadn’t been on her radar for a while when the threats began, because she was tracking other targets. Now Nixon resolved to unmask Waifu/Judische and others responsible for the death threats—and take them down for crimes they admitted to committing. This is our latest story to be turned into a MIT Technology Review Narrated podcast, which we’re publishing each week on Spotify and Apple Podcasts. Just navigate to MIT Technology Review Narrated on either platform, and follow us to get all our new content as it’s released. The must-reads I’ve combed the internet to find you today’s most fun/important/scary/fascinating stories about technology. 1 Anthropic has refused the Pentagon’s AI demands It’s holding firm on its stance: no mass surveillance of Americans, and no lethal autonomous weapons. (The Verge)+ Anthropic said “virtually no progress” had been made during recent talks. (The Hill)+ Here’s how relations between the US government and the company started to dissolve. (Vox)2 Instagram will alert parents if teens repeatedly search for suicide materialBut campaigners fear the measure could do more harm than good. (BBC)+ Instagram is working on a similar alert feature for its AI tools. (Engadget)+ Poland is weighing up banning under-15s from accessing social media. (Bloomberg $)3 ChatGPT Health regularly fails to recognize medical emergenciesIn more than half of serious cases, it advised users to delay seeking treatment. (The Guardian)+ “Dr. Google” had its issues. Can ChatGPT Health do better? (MIT Technology Review)4 The Islamic State’s online warriors are posting beyond the graveThe group is using AI to resurrect dead leaders and port them to new platforms. (404 Media)5 Vegetarians are at lower risk from five types of cancerIt suggests that avoiding meat could help to avoid certain cancers, including breast and pancreatic. (FT $)+ Interestingly, the same doesn’t apply for vegans. (Bloomberg $)+ RFK Jr. follows a carnivore diet. That doesn’t mean you should. (MIT Technology Review)6 Activists combating online abuse have been barred from AmericaAuthorities accused HateAid of participating in a “global censorship-industrial complex.” (NYT $)+ What it’s like to be banned from the US for fighting online hate. (MIT Technology Review) 7 Russians are looking for missing soldiers on Google MapsThey’re posting reviews pleading for information about missing loved ones. (New Yorker $)+ Google Maps has finally gained approval to operate in South Korea. (FT $)+ It’s hellbent on closing its final few global gaps. (Economist $)

8 Burger King’s new AI assistant will evaluate workers’ friendlinessIt’ll check interactions to make sure they’re saying please and thank you. (The Verge)+ Perplexity’s bossy new AI agent assigns work to fellow agents. (Ars Technica)9 NASA still hasn’t made it back to the moonThe mission has been dogged by delays and issues. (WP $)10 Are you Chinamaxxing yet?Everyone on TikTok is, c’mon. (Insider $) Quote of the day “This is as much of a political fight as a military use issue.” —Steven Feldstein, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment, who researches AI in warfare, explains to the Washington Post why ideological differences are likely to be worsening the rift between Anthropic and the Pentagon. One more thing One city’s fight to solve its sewage problem with sensorsIn the city of South Bend, Indiana, wastewater from people’s kitchens, sinks, washing machines, and toilets flows through 35 neighborhood sewer lines. On good days, just before each line ends, a vertical throttle pipe diverts the sewage into an interceptor tube, which carries it to a treatment plant where solid pollutants and bacteria are filtered out.As in many American cities, those pipes are combined with storm drains, which can fill rivers and lakes with toxic sludge when heavy rains or melted snow overwhelms them, endangering wildlife and drinking water supplies. But city officials have a plan to make its aging sewers significantly smarter. Read the full story.—Andrew Zaleski

We can still have nice things A place for comfort, fun and distraction to brighten up your day. (Got any ideas? Drop me a line or skeet ’em at me.) + This is a fascinating insight into Jimi Hendrix’s technical guitar wizardry 🎸+ The Romans: their lives really weren’t so different to ours, y’know.+ How the Beatles kicked back and relaxed at home when they weren’t shaping history.+ Disney composer Alan Menken is an undisputed talent.

AI is rewiring how the world’s best Go players think

Burrowed in the alleys of Hongik-dong, a hushed residential neighborhood in eastern Seoul, is a faded stone-tiled building stamped “Korea Baduk Association,” the governing body for professional Go. The game is an ancient one, with sacred stature in South Korea. But inside the building, rooms once filled with the soft clatter of hands dipping into wooden bowls of stones now echo with mouse clicks. Players hunch over their monitors and replay their matches in an AI program. Others huddle around a Go board and debate the best next move, while coaches report how their choices stack up against the AI’s. Some sit in silence, watching AI programs play against each other. Ten years ago AlphaGo, Google DeepMind’s AI program, stunned the world by defeating the South Korean Go player Lee Sedol. And in the years since, AI has upended the game. It’s overturned centuries-old principles about the best moves and introduced entirely new ones. Players now train to replicate AI’s moves as closely as they can rather than inventing their own, even when the machine’s thinking remains mysterious to them. Today, it is essentially impossible to compete professionally without using AI. Some say the technology has drained the game of its creativity, while others think there is still room for human invention. Meanwhile, AI is democratizing access to training, and more female players are climbing the ranks as a result. For Shin Jin-seo, the top-ranked Go player in the world, AI is an invaluable training partner. Every morning, he sits at his computer and opens a program called KataGo. Nicknamed “Shintelligence” for how closely his moves mimic AI’s, he traces the glowing “blue spot” that represents the program’s suggestion for the best next move, rearranging the stones on the digital grid to try to understand the machine’s thinking. “I constantly think about why AI chose a move,” he says.

When training for a match, Shin spends most of his waking hours poring over KataGo. “It’s almost like an ascetic practice,” he says. According to a study in 2022 by the Korean Baduk League, Shin’s moves match AI’s 37.5% of the time, well above the 28.5% average the study found among all players. “My game has changed a lot,” says Shin, “because I have to follow the directions suggested by AI to some extent.” The Korea Baduk Association says it has reached out to Google DeepMind in the hopes of arranging a match between Shin and AlphaGo, to commemorate the 10th anniversary of its victory over Lee. A spokesperson for Google DeepMind said the company could not provide information at this time. But if a new match does happen, Shin, who has trained on more advanced AI programs, is optimistic that he’d win. “AlphaGo still had some flaws then, so I think I could beat it if I target those weaknesses,” he says.

AI rewrites the Go playbook Go is an abstract strategy board game invented in China more than 2,500 years ago. Two players take turns placing black and white stones on a 19×19 grid, aiming to conquer territory by surrounding their opponent’s stones. It’s a game of striking mathematical complexity. The number of possible board configurations—roughly 10170—dwarfs the number of atoms in the universe. If chess is a battle, Go is a war. You suffocate your enemy in one corner while fending off an invasion in another. To train AI to play Go, a vast trove of human Go moves are fed into a neural network, a computing system that mimics the web of neurons in the human brain. AlphaGo, which was later christened AlphaGo Lee after its victory over Lee Sedol, was trained on 30 million Go moves and refined by playing millions of games against itself. In 2017, its successor, AlphaGo Zero, picked up Go from scratch. Without studying any human games, it learned by playing against itself, with moves based only on the rules of the game. The blank-slate approach proved more powerful, unconstrained by the limits of human knowledge. After three days of training, it beat AlphaGo Lee 100 games to zero. Google DeepMind retired AlphaGo that same year. But then a wave of open-source models inspired by AlphaGo Zero emerged. Today, KataGo is the program most widely used by professional Go players in South Korea. It’s faster and sharper than AlphaGo. It’s learned to predict not just who will win, but also who owns each point on the board at any given moment. While AlphaGo Zero pieced together its understanding of the board by looking at small sections, KataGo learned to read the whole board, developing better judgment for long-term strategies. Instead of just learning how to win, it learned to maximize its score. The software has reshaped how people play. For hundreds of years, professional Go players have navigated the game’s astronomical complexity by developing heuristics that replaced brute calculation. Elegant opening strategies imposed abstract order on the empty grid. Invading corners early was a bad bargain. Each generation of Go players added new principles to the canon. But “AI has changed everything,” says Park Jeong-sang, a South Korean Go commentator. “Fundamental moves that were once considered common sense aren’t played at all today, and techniques that didn’t exist before have become popular.” The starkest shift has been in opening moves. Go starts on a blank grid, and the first 50 moves were canvases for abstract thinking and creativity, where players etched their personalities and philosophies. Lee Sedol fashioned provocative moves that invited chaos. Ke Jie, a Chinese player who was defeated by AlphaGo Master in 2017, dazzled with agile, imaginative moves. Now, players memorize the same strain of efficient, calculated opening moves suggested by AI. The crux of the game has shifted to the middle moves, where raw calculation matters more than creativity. Training with AI has led to a homogenization of playing styles. Ke Jie has lamented the strain of watching the same opening moves recycled endlessly. “I feel the exact same way as the fans watching. It’s very tiring and painful to watch,” he told a Chinese news outlet in 2021. Fans revel when a player breaks from the script with offbeat moves, but those moments have become rarer. Over a third of moves by the top Go players replicate AI’s recommendations, according to a study in 2023. The first 50 moves of each game are often identical to what AI suggests, many players say. “Go has become a mind sport,” says Lee Sedol, who retired three years after his 2016 defeat to AlphaGo. “Before AI, we sought something greater. I learned Go as an art,” he says. “But if you copy your moves from an answer key, that’s no longer art.”

Playing Go is no longer about charting new frontiers, some players say, but about following the dictates of a superhuman oracle. “I used to inspire fans by advancing the techniques of Go and presenting a new paradigm,” says Lee. “My reason for playing Go has vanished.” A mysterious mind The players who have stayed in the game are trying to reinvent their craft. But it can be hard to discern what the new principles are. Disarmingly slight and formidably calm, Kim Chae-young, one of the top female Go players in the world, grew up learning the game from her father, who was also a professional Go player. But when AI began to reshape the game, she found herself starting over. “I needed time to abandon everything I had learned before,” says Kim who shared her screen with me as she pointed her cursor to the blue spots suggested by KataGo. “The intuition I had built up over the years turned out to be wrong.” As she leaned close to her monitor, her blinking screen showed the winning probabilities of each move, with no explanations. Even top players like Kim and Shin don’t understand all of AI’s moves. “It seems like it’s thinking in a higher dimension,” she says. When she tries to learn from AI, she adds, “it’s less about rationally thinking through each move, but more about developing a gut feeling—an intuition.” Researchers are trying to discover the superhuman knowledge encoded in game-playing AI programs so that humans can learn it too. In 2024, researchers at Google DeepMind extracted new chess concepts from AlphaZero, a generalized version of AlphaGo Zero that can also play chess, and taught them to chess grandmasters using chess puzzles. The Go concepts that players have picked up from AI systems so far are “probably only a small portion of what you could potentially learn,” says Nicholas Tomlin, a computer scientist at Toyota Technological Institute at Chicago, who coauthored a study probing Go concepts encoded in AlphaGo Zero. But extracting those lessons remains a struggle. “Top-tier players haven’t yet been able to deduce the general principles behind AI moves,” says Nam Chi-hyung, a Go professor at Myongji University. Although they can emulate AI’s moves, they have yet to glean a new paradigm for the game because its reasoning is a black box, she says. Go may be in an epistemic limbo. Even if AI is an opaque teacher, it’s a democratic one. It has supercharged training for female Go players, who have long been underdogs of the game. For decades, training meant studying under top male players, and the most competitive matches took place in male circles that were difficult for women to break into, says Nam. “Female players never had access to that experience,” she says. “But now they can study with AI, which has made their training environment much more favorable.” More broadly, AI has narrowed the gap between players by helping everyone perfect their opening moves. Female players have climbed the ranks over the last few years as a result. In 2022, Choi Jeong, then the top female player in the world, became the first woman to reach the finals of a major international Go tournament. Dubbed “Girl Wrestler” for her fierce, combative style of play, she took on Shin. She lost, but the match broke new ground for women in Go. In 2024, Kim made headlines for winning the Korean Go League’s postseason playoffs. She was the only female player in the tournament.

Training with AI has given Kim newfound confidence. Analyzing male players’ moves with AI has shattered their veneer of infallibility. “Before, I couldn’t gauge just how strong top male players were—they felt invincible. Now, I know that they make mistakes, and their moves aren’t always brilliant,” she says. “AI broke the psychological barrier.” Go players find a new identity Although AI has mastered Go far better than any player, fans continue to prefer watching people play. “A Go game between AI programs is not very fun for fans to watch,” says Park, the Go commentator. Such matches are too complex for fans to follow, too flawless to be thrilling, he says.

Players can mimic AI’s opening moves, but in the middle game—where the board branches into too many possibilities to memorize—their own judgment takes over. Fans revel in watching players make mistakes and mount comebacks, exuding personality in every stone on the board. Shin’s playing style is combative but marked by machinelike poise. Kim deftly navigates the most chaotic positions on the board. “In Go, every move is a choice you make, and your opponent responds with a choice of their own,” says Kim Dae-hui, 27, a Go fan and amateur player. “Watching that process unfold is fun.” With fans like Kim still watching, Shin finds meaning in his game. “I can play a kind of Go that tells a story that only a human can,” he says. After his retirement, Lee searched for a new job where he could have an edge as a human. He started making board games, giving speeches, and teaching students at a university. “I’m looking for a new domain that I can enjoy and excel at,” he says. But lately, he feels more hopeful for the game he left behind. “It’s every Go player’s dream to play a masterpiece game,” he says—a game of technical brilliance, with no mistakes, fought to a razor’s edge between evenly matched players. “It’s like a mirage,” Lee says, chuckling. “Maybe AI can help us play a masterpiece.” Shin hopes he can do that. To Shin, AI is a teacher, a companion, and a North Star. “I may be one of the strongest human players, but with AI around, I can’t be so arrogant,” he says. “AI gives me a reason to keep improving.”

Nano Banana 2: Combining Pro capabilities with lightning-fast speed

In August of last year, our Gemini Image model, Nano Banana, became a viral sensation, redefining image generation and editing. Then in November, we released Nano Banana Pro, offering users advanced intelligence and studio-quality creative control. Today, we’re bringing the best of both worlds to users across Google.Introducing Nano Banana 2 (Gemini 3.1 Flash Image), our latest state-of-the-art image model. Now you can get the advanced world knowledge, quality and reasoning you love in Nano Banana Pro, at lightning-fast speed.

Finding value with AI and Industry 5.0 transformation

In association withEY For years, Industry 4.0 transformation has centered on the convergence of intelligent technologies like AI, cloud, the internet of things, robotics, and digital twins. Industry 5.0 marks a pivotal shift from integrating emerging technologies to orchestrating them at scale. With Industry 5.0, the purpose of this interconnected web of technologies is more nuanced: to augment human potential, not just automate work, and enhance environmental sustainability. Industry 5.0 has ushered in a radically new level of collaboration between humans and machines, one that removes data silos and optimizes infrastructure, operations, and resource use to disrupt business models and create new forms of enterprise value. But without discipline in tracking value creation, investments risk being wasted on incremental efficiency gains rather than strategic growth. “To realize the promise of Industry 5.0, companies must move beyond cost and efficiency to focus on growth, resilience, and human-centric outcomes,” says Sachin Lulla, EY Americas industrials and energy transformation leader. “This requires not just new technologies, but new ways of working—where people and machines collaborate, and where value is measured not just in dollars saved, but in new opportunities created.” An MIT Technology Review Insights survey of 250 industry leaders from around the world reveals most industrial investments still target efficiency. And while the data shows human-centric and sustainable use cases deliver higher value, they are underfunded. The research shows most organizations are not realizing the full value potential of Industry 5.0 due to a combination of:

• Culture, skills, and collaboration barriers.• Tactical and misaligned technology investments.• Use-case prioritization focused on efficiency over growth, sustainability, and well-being. The barrier to achieving Industry 5.0 transformation is not only about fixing the technology, according to research from EY and Saïd Business School at the University of Oxford, it is also about bolstering human-centric elements like strategy, culture, and leadership. Companies are investing heavily in digital transformation, but not always in ways that unlock the full human potential of Industry 5.0.

“We’re not just doing digital work for work’s sake, what I call ‘chasing the digital fairies,’” says Chris Ware, general manager, iron ore digital, Rio Tinto. “We have to be very clear on what pieces of work we go after and why. Every domain has a unique roadmap about how to deliver the best value.” Download the full report. This content was produced by Insights, the custom content arm of MIT Technology Review. It was not written by MIT Technology Review’s editorial staff. It was researched, designed, and written by human writers, editors, analysts, and illustrators. This includes the writing of surveys and collection of data for surveys. AI tools that may have been used were limited to secondary production processes that passed thorough human review.

The Download: how America lost its lead in the hunt for alien life, and ambitious battery claims

This is today’s edition of The Download, our weekday newsletter that provides a daily dose of what’s going on in the world of technology. America was winning the race to find Martian life. Then China jumped in. In July 2024, NASA’s Perseverance rover came across a peculiar rocky outcrop on Mars covered in strange spots. On Earth, these marks are almost always produced by microbial life. Sure, those specks are not definitive proof of alien life. But they are the best hint yet that life may not be a one-off event in the cosmos.But the only way to know for sure is to bring a sample of that rock home to study.Now, just over a year and a half later, the project to do so is on life support, with zero funding flowing in 2026 and little backing left in Congress. As a result, those oh-so-promising rocks may be stuck out there forever.This also means that, in the race to find evidence of alien life, America has effectively ceded its pole position to its greatest geopolitical rival: China. The superpower is moving full steam ahead with its own version of the mission to bring the rock samples home. It’s leaner than America and Europe’s mission, and the rock samples it will snatch from Mars will likely not be as high quality. But that won’t be the headline people remember—the one in the scientific journals and the history books.Nearly a dozen project insiders and scientists in both the US and China shared with me the story of how America blew its lead in the new space race. It’s full of wild dreams and promising discoveries—as well as mismanagement, eye-watering costs, and, ultimately, anger and disappointment. Read the full story.

—Robin George Andrews This article is also part of the Big Story series: MIT Technology Review’s most important, ambitious reporting. The stories in the series take a deep look at the technologies that are coming next and what they will mean for us and the world we live in. Check out the rest of them here.

This company claims a battery breakthrough. Now they need to prove it. When a company claims to have created what’s essentially the holy grail of batteries, there are bound to be some questions. Interest has been swirling since Donut Lab, a Finnish company, announced last month that it had a new solid-state battery technology, one that was ready for large-scale production. The company said its batteries can charge super-fast and have a high energy density that would translate to ultra-long-range EVs. What’s more, it claimed the cells can operate safely in the extreme heat and cold, contain “green and abundant materials,” and would cost less than lithium-ion batteries do today. It sounded amazing—this sort of technology could transform the EV industry. But many quickly wondered if it was all too good to be true. Let’s dig into why this company is making news, why many experts are skeptical, and what it all means for the battery industry right now. —Casey Crownhart This article is from The Spark, MIT Technology Review’s weekly climate newsletter. To receive it in your inbox every Wednesday, sign up here.

The must-reads I’ve combed the internet to find you today’s most fun/important/scary/fascinating stories about technology. 1 Chinese law enforcement tried to get ChatGPT to discredit Japan’s prime ministerOpenAI claims the chatbot refused to help plan an online smear campaign. (Axios)+ The user asked ChatGPT to edit status reports on covert influence operations. (Bloomberg $) 2 Meta’s AI is sending junk tips to child abuse investigatorsNot only are they a serious drain on resources—they’re hindering investigations. (The Guardian)+ US investigators are using AI to detect child abuse images made by AI. (MIT Technology Review)3 A judge has dismissed xAI’s lawsuit against OpenAIElon Musk’s startup has failed to prove that its rival committed any misconduct. (Ars Technica)+ xAI had accused former employees of taking trade secrets to OpenAI. (Reuters)+ It could refile, but would need to modify its claims. (The Verge)4 China appears to be masking regular drone flightsIn what could be rehearsals for a potential invasion of Taiwan. (Reuters)+ Taiwan’s “silicon shield” could be weakening. (MIT Technology Review)5 Pro-AI super PACs are raising huge sums ahead of the US midterm electionsThey’re making significantly higher sums than their pro-regulation counterparts. (FT $)+ Anthropic is backing a regulation-friendly PAC group called Public First Action. (NYT $) 6 Experts are worried about AI slop videos’ effects on child developmentThe nonsensical clips tend to lack structure and confuse children.(NYT $) 7 Around 400 million people are living with long covidAnd its effects are rippling far beyond its physical symptoms. (Bloomberg $)+ Scientists are finding signals of long covid in blood. They could lead to new treatments. (MIT Technology Review) 8 Tech bros are opting out of interviews with mainstream mediaAnd gravitating toward much less critical online streams. (New Yorker $) 9 The ISS is surprisingly vulnerableThere’s a major gap in its critical defenses. (Wired $)+ Data centers are heading to space, and our laws aren’t ready. (Rest of World)+ Meet the astronaut training tourists to fly in the world’s first commercial space station. (MIT Technology Review)

10 We’ve lost our appetite for fake meat 🍔Even plant-based meat makers are admitting some products don’t taste great. (Economist $)+ The price of (real) beef has soared recently. (The Guardian)+ Here’s what a lab-grown burger tastes like. (MIT Technology Review)

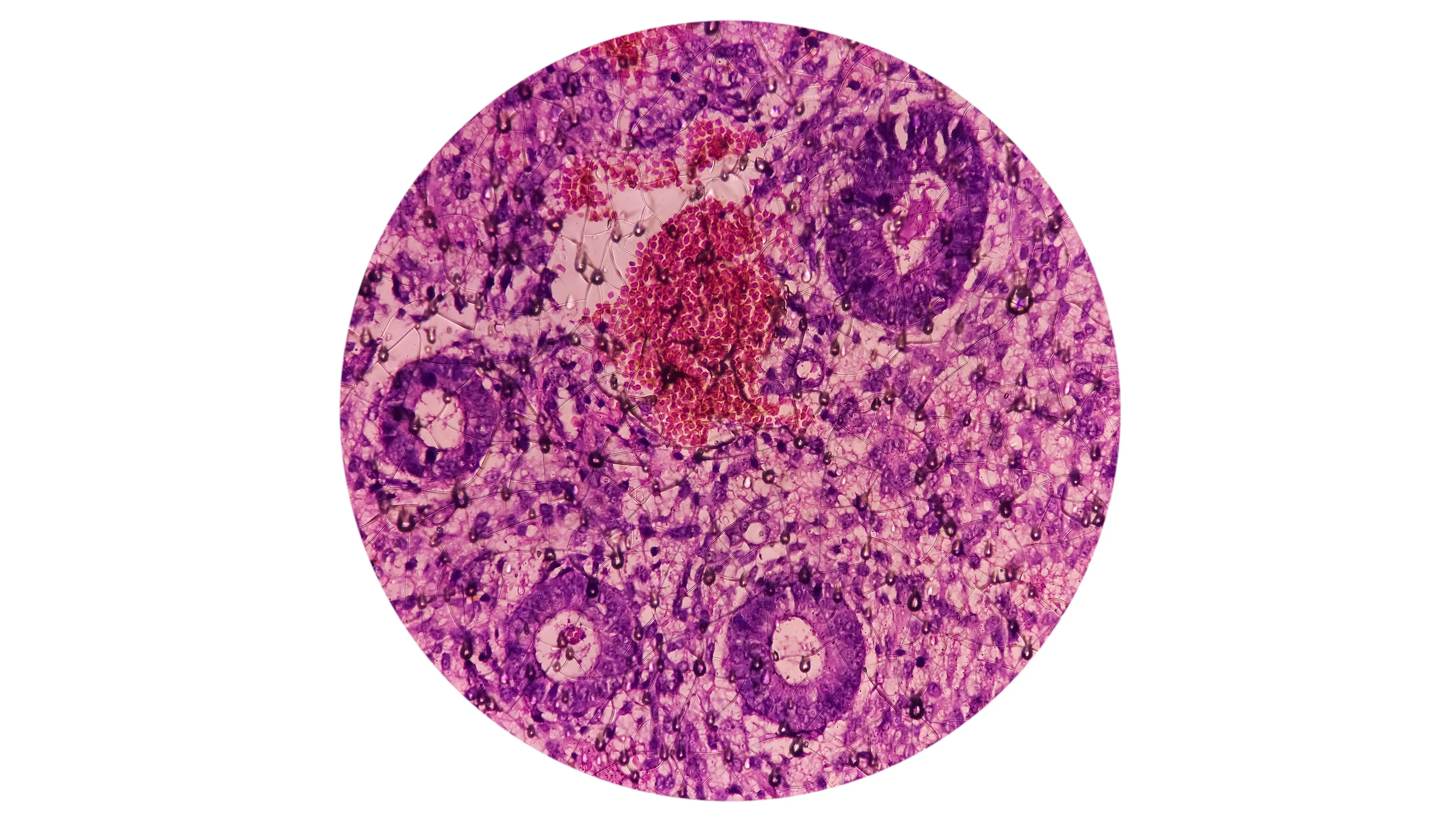

Quote of the day “We are using carrots and sticks.” —Seth Besmertnik, chief executive of digital marketing startup Conductor, explains his approach to vigorously vetting his workers’ AI literacy to the Wall Street Journal. One more thing Tiny faux organs could crack the mystery of menstruation

No one is entirely sure how—or why—the human body choreographs menstruation; the monthly dance of cellular birth, maturation, and death. Many people desperately need treatments to make their period more manageable, but it’s difficult for scientists to design medications without understanding how menstruation really works.That understanding could be in the works, thanks to endometrial organoids—biomedical tools made from bits of the tissue that lines the uterus, called the endometrium. Organoids have already provided insights into how endometrial cells communicate and coordinate, and why menstruation is routine for some people and fraught for others—and some researchers are hopeful that these early results mark the dawn of a new era. Read the full story. —Saima Sidik We can still have nice things A place for comfort, fun and distraction to brighten up your day. (Got any ideas? Drop me a line or skeet ’em at me.) + The crazy but true story about the Elder Scrolls III fans who built a world the size of a small country into it.+ How to master the tricky art of making the perfect sourdough loaf.+ This adorable Pika is the real-life inspiration for Pikachu.+ How many of these animated classics have you seen?

Policy Shock: Big Tech Told to Power Its Own AI Buildout