Your Gateway to Power, Energy, Datacenters, Bitcoin and AI

Dive into the latest industry updates, our exclusive Paperboy Newsletter, and curated insights designed to keep you informed. Stay ahead with minimal time spent.

Discover What Matters Most to You

AI

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry.

Bitcoin:

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry.

Datacenter:

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry.

Energy:

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry.

Discover What Matter Most to You

Featured Articles

Nvidia lines up partners to boost security for industrial operations

Akamai extends its micro-segmentation and zero-trust security platform Guardicore to run on Nvidia BlueField GPUs The integration offloads user-configurable security processes from the host system to the Nvidia BlueField DPU and enables zero-trust segmentation without requiring software agents on fragile or legacy systems, according to Akamai. Organizations can implement this hardware-isolated, “agentless” security approach to help align with regulatory requirements and lower their risk profile for cyber insurance. “It delivers deep, out-of-band visibility across systems, networks, and applications without disrupting operations. Security policies can be enforced in real time and are capable of creating a strong protective boundary around critical operational systems. The result is trusted insight into operational activity and improved overall cyber resilience,” according to Akamai. Forescout works with Nvidia to bring zero-trust technology to OT networks Forescout applies network segmentation to contain lateral movement and enforce zero-trust controls. The technology would be further integrated into partnership work already being done by the two companies. By running Forescout’s on-premises sensor directly on the Nvidia BlueField, part of Nvidia Cybersecurity AI platform, customers can offload intensive computing tasks, such as deep packet inspections. This speeds up data processing, enhances asset intelligence, and improves real-time monitoring, providing security teams with the insights needed to stay ahead of emerging threats, according to Forescout. Palo Alto to demo Prisma AIRS AI Runtime Security on Nvidia BlueField DPU Palo Alto Networks recently partnered with Nvidia to run its Prisma AI-powered Radio Security(AIRs) package on the Nvidia BlueField DPU and will show off the technology at the conference. The technology is part of the Nvidia Enterprise AI Factory validated design and can offer real-time security protection for industrial network settings. “Prisma AIRS AI Runtime Security delivers deep visibility into industrial traffic and continuous monitoring for abnormal behavior. By running these security services on Nvidia BlueField, inspection

Pure Storage becomes Everpure, acquires 1touch

Other recent research confirms this. In an October Cisco survey of over 8,000 AI leaders, only 35% of companies have clean, centralized data with real-time integration for AI agents. And by 2027, according to IDC, companies that don’t prioritize high-quality, AI-ready data will struggle scaling gen AI and agentic solutions, resulting in a 15% productivity loss. “Every enterprise is talking about AI, but most aren’t AI ready because their data is fragmented and poorly cataloged,” says Brad Gastwirth, global head of research and market intelligence at Circular Technology, a supply chain consultancy. “If Everpure can help turn storage into a structured, intelligent data foundation, that could materially shorten the path from proof of concept to production AI.” It’s not an easy process. It could take years to shift from being viewed primarily as a storage hardware company to a data platform company, Gastwirth says. “There is product integration to get right, but there is also a commercial shift. Sales teams need to sell differently, customers need to budget differently, and the market needs proof points.” And there are many companies in the race to be the data platform for AI. “The difference is where it sits in the stack,” he says. “If Everpure can bake more intelligence directly into the core storage layer instead of layering tools on top, that can actually simplify things.” Putting the control layer closer to the data can be helpful as companies deploy agentic AI. AI agents need to have good access to data to function well, whether as part of their training, in RAG embedding, or via MPC servers. But ensuring that agents only access the data they’re supposed to is a challenge. “The shift to agentic AI is a big reason why you’d want to have your data intelligence tied to your data

Peptides are everywhere. Here’s what you need to know.

MIT Technology Review Explains: Let our writers untangle the complex, messy world of technology to help you understand what’s coming next. You can read more from the series here. Want to lose weight? Get shredded? Stay mentally sharp? A wellness influencer might tell you to take peptides, the latest cure-all in the alternative medicine arsenal. People inject them. They snort them. They combine them into concoctions with superhero names, like the Wolverine stack. Matt Kaeberlein, a longevity researcher, first started hearing about peptides a few years ago. “At that point it was mostly functional medicine doctors that were using peptides,” he says, referring to physicians who embrace alternative medicine and supplements. “In the last six months, it’s kind of gone crazy.” Peptides have gone mainstream. At the health-technology startup Superpower in Los Angeles, employees can get free peptide shots on Fridays. At a health food store in Phoenix, a sidewalk sign reads, “We have peptides!” At a tae kwon do center in South Carolina, a peptide wholesaler hosts an informational evening. On social media, they’re everywhere. And that popularity seems poised to grow; Department of Health and Human Services secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has promised to end the FDA’s “aggressive suppression” of peptides.

The benefits and risks of many of these compounds, however, are largely unknown. Some of the most popular peptides have never been tested in human trials. They are sold for research purposes, not human consumption. Some are illegal knockoffs of wildly successful weight-loss medicines. The vast majority come from China, a fact that has some legislators worried. Last week, Senator Tom Cotton urged the head of the FDA to crack down on illegal shipments of peptides from China. In the absence of regulatory oversight, some people are sending the compounds they purchase off for independent testing just to ensure that the product is legit. What is a peptide? A peptide is simply a short string of amino acids, the building blocks of proteins. “Scientists generally think of peptides as very small protein fragments, but we don’t really have a precise cutoff between a peptide and a protein,” says Paul Knoepfler, a stem-cell researcher at the University of California, Davis. Insulin is a peptide, as is human growth hormone. So are some neurotransmitters, like oxytocin.

But when wellness influencers talk about peptides, they’re often referring to particular compounds—formulated as injections, pills, or nasal sprays—that have become trendy lately. Some of these peptides are FDA-approved prescription medications. GLP-1 medicines, for example, are approved to treat diabetes and obesity but are also easily accessible online to almost anyone who wants to use them. Many sites sell microdoses of GLP-1s with claims that they can “support longevity,” reduce cognitive decline, or curb inflammation. Many more peptides are experimental. “The majority fall into the unapproved bucket,” says Kaeberlein, who is chief executive officer of Optispan, a Seattle-based health-care technology company focused on longevity. That bucket includes drugs that promote the release of growth hormones, like TB-500, CJC-1295, and ipamorelin, and compounds said to promote tissue repair and wound healing, like BPC-157 and GHK-Cu. It’s primarily these unapproved compounds that have raised concerns. “Anybody can set up an online shop selling research-grade peptides,” says Tenille Davis, a pharmacist and chief advocacy officer at the Alliance for Pharmacy Compounding, a trade organization representing more than 600 pharmacies. “And nobody knows what’s even in the vials.” It’s not just fitness gurus, biohackers, and longevity fanatics who are taking these experimental drugs. Kaeberlein recalls hearing about an acquaintance whose doctor prescribed her unapproved peptides. She was “just a typical upper-middle-class woman,” he says. “That’s when it really hit me that this has sort of gone relatively mainstream.” What do peptides do? All kinds of things, purportedly. GHK-Cu is supposed to help with wound healing and collagen production. BPC-157 is said to promote tissue repair and curb inflammation, TB-500 to foster blood vessel formation. Here’s the caveat: The evidence for these benefits comes largely from animal studies and online testimonials, not human trials. “There’s no human clinical evidence to show that they even do what people are claiming that they do,” says Stuart Phillips, a muscle physiologist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. “So it could be just a giant rip-off.” Some experimental peptides probably do have beneficial wound healing properties or regenerative effects, Kaeberlein says. For BPC-157, for example, “the animal data is compelling,” he says. But there are still plenty of unknowns: What is the right dosage? How long should you take it? What’s the best way to administer it? Those are questions that can be answered only through rigorous clinical trials. In the absence of those studies, doctors “just make up their own protocols,” he says. Some consumers go the DIY route, reconstituting powdered peptides and injecting their own concoctions at home. So why am I seeing ads for these peptide therapies if they’re not approved? Federal law prohibits companies from marketing medications that haven’t been approved. That includes most peptides, which are regulated as small molecules, not dietary supplements. (Two notable exceptions are collagen peptides and creatine peptides, often sold as powders.) The law is designed to protect consumers from drugs that haven’t been proved safe and effective. But it doesn’t stop labs from making peptides for research purposes. “Most of the peptides being consumed in the marketplace now are being sold by these online companies that are selling them labeled for research use only,” Davis says. The vials often bear disclaimers that clearly say as much: “For research use only” or “Not for human consumption.” It’s illegal to market these products for human use, but “the websites make it pretty clear that the buyers are intended to be using these products themselves,” she says.

The practice isn’t legal, but enforcement has been sporadic. “FDA sends warning letters, shuts down companies. But because it’s all online, they have a really hard time keeping up with these entities,” Davis says. And companies have plenty of incentive to keep illegally marketing the products. “They can make millions of dollars without having to spend money and time doing research,” Knoepfler says. “It’s a cash grab.” Compounding pharmacies, which are legally allowed to create bespoke medications by mixing bulk active ingredients, often get requests to dispense peptides, but most peptides don’t meet the eligibility criteria for compounding. This has always been the case, but in 2023 the FDA explicitly added several common experimental peptides to the list of bulk substances that cannot be compounded because of safety concerns. “It put an exclamation point on policy that was already in place,” Davis says. Many GLP-1 medications are available from compounding pharmacies. That used to be accepted because the drugs were in short supply. Now, however, supplies of most of these medications are stable, and sellers are under increasing pressure from regulators to stop mass-marketing these drugs. What’s the harm in trying them? Peptides sold for research purposes come from labs with little regulatory oversight. “When you buy stuff online intended for research grade, you have no idea what’s in the vial that you’re getting. You have no idea the sterility practices that it was manufactured under, or what sort of impurities might be in the vial,” Davis says. Phillips has heard some people say they send their peptides for third-party testing to ensure that they’re pure, “like it’s some kind of flex,” he says. “And I’m like, ‘Well, you just proved that this stuff lives in the shadows, for crying out loud.’” Finnrick Analytics, a peptide-testing startup in Austin, Texas, has analyzed the purity and potency of more than 5,000 samples of 15 different peptides from 173 vendors. The results show that the quality varies substantially from vendor to vendor and even batch to batch. For example, the company tested nearly 450 samples of BPC-157 from 64 vendors. In some cases, the vials sold as BPC-157 didn’t contain the compound at all. In those that did, the purity varied from about 82% to 100%. Perhaps more worrying, 8% of all the peptide samples Finnrick tested had measurable levels of endotoxins, bacterial fragments that can cause fever and chills or, in larger doses, septic shock. The health risks aren’t just hypothetical. In 2025, two women had to be hospitalized and placed on ventilators after receiving peptide injections at a longevity conference in Las Vegas. Both recovered, and it’s still not clear whether they reacted to the peptides themselves or to some impurity in the vials.

“The idea that all peptides are safe and all peptides are natural is just nonsense,” Kaeberlein says. “I tend to consider myself fairly libertarian when it comes to what people want to do for their health,” he adds. “If you want to take an experimental drug, that’s up to you.” But the problem with unregulated experimental therapies is that it’s exceedingly difficult to assess benefit and harm. “The relatively small percentage of people that are bad actors will be bad actors, and they will dishonestly market this stuff to people who aren’t equipped to really understand the true risks and rewards,” he says. And, like any drug, peptides come with a risk of side effects. For approved medications, these are detailed right on the package insert. But for many experimental peptides, there hasn’t been enough research to understand what those side effects might be. Some researchers have warned that peptides that promote growth or blood vessel formation might also foster the growth of cancers.

For competitive athletes who use peptides, meanwhile, the risks include not just possible health problems but suspension. Some peptides, like BPC-157, are banned by the World Anti-Doping Agency. The FDA has undergone a pretty substantial overhaul under the Trump administration. Are the regulations around peptides likely to change? I don’t have a crystal ball, but it seems likely. In May 2025, US health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. joined the longevity enthusiast and biohacker Gary Brecka on his podcast The Ultimate Human and promised to “end the war at FDA against alternative medicine—the war on stem cells, the war on chelating drugs, the war on peptides.” Knoepfler anticipates that Kennedy will force the FDA to allow compounding of some of the most popular peptides, like BPC-157 and GHK-Cu. “Such a step would put public health at great risk, while giving compounders and likely wellness influencers a lot more profit,” he says. The FDA seems intent on cracking down on GLP-1 copycats, however. In early February, commissioner Marty Makary posted on X that the agency would take “swift action against companies mass-marketing illegal copycat drugs, claiming they are similar to FDA-approved products.”

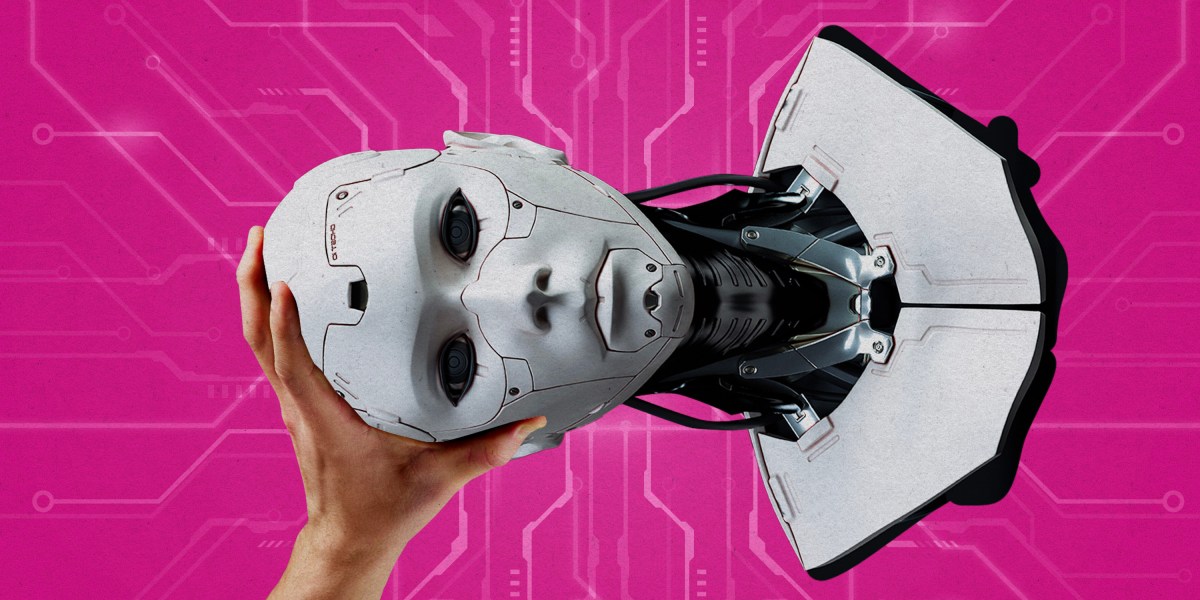

The human work behind humanoid robots is being hidden

This story originally appeared in The Algorithm, our weekly newsletter on AI. To get stories like this in your inbox first, sign up here. In January, Nvidia’s Jensen Huang, the head of the world’s most valuable company, proclaimed that we are entering the era of physical AI, when artificial intelligence will move beyond language and chatbots into physically capable machines. (He also said the same thing the year before, by the way.) The implication—fueled by new demonstrations of humanoid robots putting away dishes or assembling cars—is that mimicking human limbs with single-purpose robot arms is the old way of automation. The new way is to replicate the way humans think, learn, and adapt while they work. The problem is that the lack of transparency about the human labor involved in training and operating such robots leaves the public both misunderstanding what robots can actually do and failing to see the strange new forms of work forming around them. Consider how, in the AI era, robots often learn from humans who demonstrate how to do a chore. Creating this data at scale is now leading to Black Mirror–esque scenarios. A worker in Shanghai, for example, recently spent a week wearing a virtual-reality headset and an exoskeleton while opening and closing the door of a microwave hundreds of times a day to train the robot next to him, Rest of World reported. In North America, the robotics company Figure appears to be planning something similar: It announced in September it would partner with the investment firm Brookfield, which manages 100,000 residential units, to capture “massive amounts” of real-world data “across a variety of household environments.” (Figure did not respond to questions about this effort.)

Just as our words became training data for large language models, our movements are now poised to follow the same path. Except this future might leave humans with an even worse deal, and it’s already beginning. The roboticist Aaron Prather told me about recent work with a delivery company that had its workers wear movement-tracking sensors as they moved boxes; the data collected will be used to train robots. The effort to build humanoids will likely require manual laborers to act as data collectors at massive scale. “It’s going to be weird,” Prather says. “No doubts about it.” Or consider tele-operation. Though the endgame in robotics is a machine that can complete a task on its own, robotics companies employ people to operate their robots remotely. Neo, a $20,000 humanoid robot from the startup 1X, is set to ship to homes this year, but the company’s founder, Bernt Øivind Børnich, told me recently that he’s not committed to any prescribed level of autonomy. If a robot gets stuck, or if the customer wants it to do a tricky task, a tele-operator from the company’s headquarters in Palo Alto, California, will pilot it, looking through its cameras to iron clothes or unload the dishwasher.

This isn’t inherently harmful—1X gets customer consent before switching into tele-operation mode—but privacy as we know it will not exist in a world where tele-operators are doing chores in your house through a robot. And if home humanoids are not genuinely autonomous, the arrangement is better understood as a form of wage arbitrage that re-creates the dynamics of gig work while, for the first time, allowing physical tasks to be performed wherever labor is cheapest. We’ve been down similar roads before. Carrying out “AI-driven” content moderation on social media platforms or assembling training data for AI companies often requires workers in low-wage countries to view disturbing content. And despite claims that AI will soon enough train on its outputs and learn on its own, even the best models require an awful lot of human feedback to work as desired. These human workforces do not mean that AI is just vaporware. But when they remain invisible, the public consistently overestimates the machines’ actual capabilities. That’s great for investors and hype, but it has consequences for everyone. When Tesla marketed its driver-assistance software as “Autopilot,” for example, it inflated public expectations about what the system could safely do—a distortion a Miami jury recently found contributed to a crash that killed a 22-year-old woman (Tesla was ordered to pay $240 million in damages). The same will be true for humanoid robots. If Huang is right, and physical AI is coming for our workplaces, homes, and public spaces, then the way we describe and scrutinize such technology matters. Yet robotics companies remain as opaque about training and tele-operation as AI firms are about their training data. If that does not change, we risk mistaking concealed human labor for machine intelligence—and seeing far more autonomy than truly exists.

The Download: Chicago’s surveillance network, and building better bras

This is today’s edition of The Download, our weekday newsletter that provides a daily dose of what’s going on in the world of technology. Inside Chicago’s surveillance panopticon Chicago has tens of thousands of surveillance cameras—up to 45,000, by some estimates. That’s among the highest numbers per capita in the US. Chicago boasts one of the largest license plate reader systems in the country, and the ability to access audio and video surveillance from independent agencies such as the Chicago Public Schools, the Chicago Park District, and the public transportation system as well as many residential and commercial security systems such as Ring doorbell cameras.Law enforcement and security advocates say this vast monitoring system protects public safety and works well.

But activists and many residents say it’s a surveillance panopticon that creates a chilling effect on behavior and violates guarantees of privacy and free speech. Read the full story. —Rod McCullom

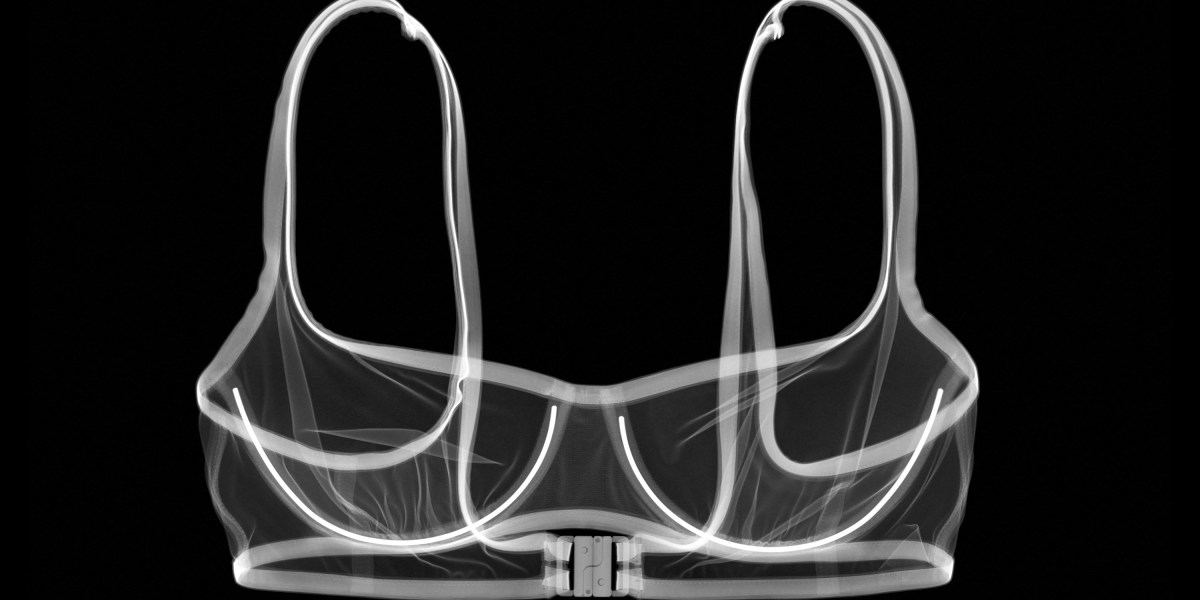

Job titles of the future: Breast biomechanic Twenty years ago, Joanna Wakefield-Scurr was having persistent pain in her breasts. Her doctor couldn’t diagnose the cause but said a good, supportive bra could help. A professor of biomechanics, Wakefield-Scurr thought she could do a little research and find a science-backed option. Two decades later, she’s still looking.Wakefield-Scurr now leads an 18-person team at the Research Group in Breast Health at the University of Portsmouth in the UK. And as more women take up high-impact sports, the need to understand what makes a good bra grows, she says her lab can’t keep up with demand. Read the full story. —Sara Harrison These stories are both from the next print issue of MIT Technology Review magazine, which is all about crime. If you haven’t already, subscribe now to receive future issues once they land. The must-reads I’ve combed the internet to find you today’s most fun/important/scary/fascinating stories about technology.

1 Inside ICE’s plans to build huge detention centers across the USThe identities of the personnel who authorized it have been revealed in metadata. (Wired $)+ A UK tourist with a valid visa was detained by ICE for six weeks. (The Guardian) 2 The UAE says it was targeted by a wave of AI-backed cyberattacksAuthorities said the attacks marked a major shift in methods, but didn’t elaborate. (Bloomberg $)+ New cybersecurity rules are hobbling small defense suppliers. (Reuters)+ AI is already making online crimes easier. It could get much worse. (MIT Technology Review)3 What does the public really think about AI?Tech leaders are worried they might not be fully onboard with their missions. (NYT $)+ How social media encourages the worst of AI boosterism. (MIT Technology Review) 4 It looks like X really is pushing its users further to the rightAs well as attracting more conservative thinkers in the first place. (NY Mag $)+ The platform is currently disputing a major European fine. (Politico $)5 Meet the farmers standing up to data center buildersThey’re turning down deals worth millions for the land they’ve worked for decades. (The Guardian)+ A data center venture launched at the White House isn’t delivering on its promises. (The Information $)+ Data centers are amazing. Everyone hates them. (MIT Technology Review) 6 America has a plan to fight back against China’s AIIt hopes to send Tech Corps volunteers around the world to promote its own national efforts. (Rest of World)+ China’s plan to lure in new AI customers? Bubble tea. (FT $)+ The State of AI: Is China about to win the race? (MIT Technology Review) 7 Clouds are a major climate problem ☁️They’re making it harder for scientists to model the weather accurately. (Quanta Magazine)+ The building legal case for global climate justice. (MIT Technology Review) 8 AI is still hopeless at reading PDFsBut companies keep deploying it across work systems anyway. (The Verge) 9 A “Fitbit for farts” could help analyze your gastrointestinal healthIf you don’t mind wearing a sensor tucked into your underwear, that is. (WSJ $)10 Gen Z is fascinated by corporate culture 💼TikTok’s “WorkTok” videos are very effective at romanticizing the daily grind. (FT $)

Quote of the day “It also takes a lot of energy to train a human. It takes like 20 years of life and all of the food you eat during that time before you get smart.”

—Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, compares the environmental impact of training AI’s vast models to the effort required to train a human during an event in India, TechCrunch reports. One more thing How one mine could unlock billions in EV subsidiesOn a pine farm north of the tiny town of Tamarack, Minnesota, Talon Metals has uncovered one of America’s densest nickel deposits—and now it wants to begin extracting it.If regulators approve the mine, it could mark the starting point in what the company claims would become the country’s first complete domestic nickel supply chain, running from the bedrock beneath the Minnesota earth to the batteries in electric vehicles across the nation.MIT Technology Review wanted to provide a clearer sense of the law’s on-the-ground impact by zeroing in on a single project and examining how these rich subsidies could be unlocked at each point along the supply chain. Take a look at what we found out. —James Temple

We can still have nice things A place for comfort, fun and distraction to brighten up your day. (Got any ideas? Drop me a line or skeet ’em at me.) + Alysa Liu’s gold medal-winning Winter Olympics figure skating route is truly amazing.+ Mmm, delicious ancient Roman pizza.+ It’s not every day you find 2,000 year-old footprints while walking your dog 👣+ Nature is full of surprises, and so are the winners of this year’s Sony World Photography Awards.

Inside Chicago’s surveillance panopticon

Early on the morning of September 2, 2024, a Chicago Transit Authority Blue Line train was the scene of a random and horrific mass shooting. Four people were shot and killed on a westbound train as it approached the suburb of Forest Park. The police swiftly activated a digital dragnet—a surveillance network that connects thousands of cameras in the city. The process began with a quick review of the transit agency’s surveillance cameras, which captured the alleged gunman shooting the victims execution style. Law enforcement followed the suspect, through real-time footage, across the rapid-transit system. Police officials circulated the images to transit staff and to thousands of officers. An officer in the adjacent suburb of Riverdale recognized the suspect from a previous arrest. By the time he was captured at another train station, just 90 minutes after the shooting, authorities already had his name, address, and previous arrest history. Little of this process would come as much surprise to Chicagoans. The city has tens of thousands of surveillance cameras—up to 45,000, by some estimates. That’s among the highest numbers per capita in the US. Chicago boasts one of the largest license plate reader systems in the country, and the ability to access audio and video surveillance from independent agencies such as the Chicago Public Schools, the Chicago Park District, and the public transportation system as well as many residential and commercial security systems such as Ring doorbell cameras. Law enforcement and security advocates say this vast monitoring system protects public safety and works well. But activists and many residents say it’s a surveillance panopticon that creates a chilling effect on behavior and violates guarantees of privacy and free speech. Black and Latino communities in Chicago have historically been targeted by excessive policing and surveillance, says Lance Williams, a scholar of urban violence at Northeastern Illinois University. That scrutiny has created new problems without delivering the promised safety, he suggests. In order to “solve the problem of crime or violence and make these communities safer,” he says, “you have to deal with structural problems,” such as the shortage of livable-wage jobs, affordable housing, and mental-health services across the city.

Recent years have seen some effective pushback against the surveillance. Until recently, for example, the city was the largest customer of ShotSpotter acoustic sensors, which are designed to detect gunfire and alert police. The system was introduced in a small area on the South Side in 2012. By 2018, an area of about 136 square miles—some 60% of the city—was covered by the acoustic surveillance network. Critics questioned ShotSpotter’s effectiveness and objected that the sensors were installed largely in Black and Latino neighborhoods. Those critiques gained urgency with the fatal shooting in March 2021 of a 13-year-old, Adam Toledo, by police responding to a ShotSpotter alert. The tragedy became the touchstone of the #StopShotSpotter protest movement and one of the major issues in Brandon Johnson’s successful mayoral campaign in 2023. When he reached office, Johnson followed through, ending the city’s contract with SoundThinking, the San Francisco Bay Area company behind ShotSpotter. In total, it’s estimated the city paid more than $53 million for the system.

In response to a request for comment, SoundThinking said that ShotSpotter enables law enforcement “to reach the scene faster, render aid to victims, and locate evidence more effectively.” It stated the company “plays no part in the selection of deployment areas” but added: “We believe communities experiencing the highest levels of gun violence deserve the same rapid emergency response as any other neighborhood.” While there has been successful resistance to police surveillance in the nation’s third-largest city, there are also countervailing forces: governments and officials in Chicago and the surrounding suburbs are moving to expand the use of surveillance, also in response to public pressure. Even the victory against acoustic surveillance might be short-lived. Early last year, the city issued a request for proposals for gun violence detection technology. Many people in and around Chicago—digital privacy and surveillance activists, defense attorneys, law enforcement officials, and ordinary citizens—are part of this push and pull. Here are some of their stories. Alejandro Ruizesparza and Freddy MartinezCofounders, Lucy Parsons Labs Oak Park, a quiet suburb at Chicago’s western border, is the birthplace of Ernest Hemingway. It includes the world’s largest collection of Frank Lloyd Wright–designed buildings and homes. Until recently, the village of Oak Park was also the center of a three-year-long campaign against an unwelcome addition to its manicured lawns and Prairie-style architecture: automated license plate readers from a company called Flock Safety. These are high-speed cameras that automatically scan license plates to look for stolen or wanted vehicles, or for drivers with outstanding warrants. Freddy Martinez (left) and Alejandro Ruizesparza (right) direct Lucy Parsons Labs, a charitable organization focused on digital rights.AKILAH TOWNSEND An Oak Park group called Freedom to Thrive—made up of parents, activists, lawyers, data scientists, and many others—suspected that this technology was not a good or equitable addition to their neighborhood. So the group engaged the Chicago-based nonprofit Lucy Parsons Labs to help navigate the often intimidating process of requesting license plate reader data under the Illinois Freedom of Information Act. Lucy Parsons Labs, which is named for a turn-of-the-century Chicago labor organizer, investigates technologies such as license plate readers, gunshot detection systems, and police bodycams. LPL provides digital security and public records training to a variety of groups and is frequently called on to help community members audit and analyze surveillance systems that are targeting their neighborhoods. It’s led by two first-generation Mexican-Americans from the city’s Southwest Side. Alejandro Ruizesparza has a background in community organizing and data science. Freddy Martinez was also a community organizer and has a background in physics.

The group is now approaching its 10th year, but it was an all-volunteer effort until 2022. That’s when LPL received its first unrestricted, multi-year operational grant from a large foundation: the Chicago-based John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, known worldwide for its so-called “genius grants.” A grant from the Ford Foundation followed the next year. The additional resources—a significant amount compared with the previous all-volunteer budget, acknowledges Ruizesparza—meant the two cofounders and two volunteers became full-time employees. But the group is determined not to become “too comfortable” and lose its edge. There is a tenacity to Lucy Parsons Labs’ work—a “sense of scrappiness,” they say—because “we did so much of this work with no money.” One of LPL’s primary strategies is filing extensive FOIA requests for raw data sets of police surveillance. The process can take a while, but it often reveals issues. In the case of Oak Park, the FOIA requests were just one tool that Freedom to Thrive and LPL used to sort out what was going on. The data revealed that in the first 10 months of operation, the eight Flock license plate readers the town had deployed scanned 3,000,000 plates. But only 42 scans led to an alert—an infinitesimal yield of 0.000014%.

At the same time, the impacts of those few flagged license plates were disproportionate. While Oak Park’s population of about 53,000 is only 19% Black, Black drivers made up 85% of those flagged by the Flock cameras, seemingly amplifying what were already concerning racial disparities in the village’s traffic stops. Flock did not respond to a request for comment. “We became almost de facto experts in navigating the process and the law. I think that sort of speaks to some of the DIY punk aesthetic.” Freddy Martinez, cofounder, Lucy Parsons Labs LPL brings a mix of radical politics and critical theory to its mission. Most surveillance technologies are “largely extensions of the plantation systems,” says Ruizesparza. The comparison makes sense: Many slaveholding communities required enslaved persons to carry signed documents to leave plantations and wear badges with numbers sewn to their clothing. The group says it aims to empower local communities to push back against biased policing technologies through technical assistance, training, and litigation—and to demystify algorithms and surveillance tools in the process. “When we talk to people, they realize that you don’t need to know how to run a regression to understand that a technology has negative implications on your life,” says Ruizesparza. “You don’t need to understand how circuits work to understand that you probably shouldn’t have all of these cameras embedded in only Black and brown regions of a city.”

The group came by some of its techniques through experimentation. “When LPL was first getting started, we didn’t really feel like FOIA would have been a good way of getting information. We didn’t know anything about it,” says Martinez. “Along the way, we were very successful in uncovering a lot of surveillance practices.” One of the covert surveillance practices uncovered by those aggressive FOIA requests, for example, was the Chicago Police Department’s use of “Stingray” equipment, portable surveillance devices deployed to track and monitor mobile phones. The contentious issue of Oak Park’s license plate readers was finally put to a vote in late August. The village trustees voted 5–2 to terminate the contract with Flock Safety. Since then, community-based groups from across the country—as far away as California—have contacted LPL to say the Chicago collective’s work has inspired their own efforts, says Martinez: “We became almost de facto experts in navigating the process and the law. I think that sort of speaks to some of the DIY punk aesthetic.” Brian Strockis Chief, Oak Brook Police Department If you drive about 20 miles west of Chicago, you’ll find Oakbrook Center, one of the nation’s leading luxury shopping destinations. The open-air mall includes Neiman-Marcus, Louis Vuitton, and Gucci and attracts high-end shoppers from across the region. It’s also become a destination for retail theft crews that coordinate “smash and grabs” and often escape with thousands of dollars’ worth of inventory that can be quickly sold, such as sunglasses or luxury handbags. In early December, police say, a Chicago man tried to lead officers on what could have been a dangerous high-speed chase from the mall. Patrol cars raced to the scene. So did a “first responder drone,” built by Flock Safety and deployed by the Oak Brook Police Department. The drone identified the suspect vehicle from the mall parking lot using its license plate reader and snapped high-definition photos that were texted to officers on the ground. The suspect was later tracked to Chicago, where he was arrested. Brian Strockis, chief of the Oak Brook Police Department, led the way in introducing drones as first responders in the state of Illinois.AKILAH TOWNSEND This was the type of outcome that Brian Strockis, chief of the Oak Brook Police Department, hoped for when he pioneered the “drone as first responder,” or DFR, program in Illinois. A longtime member of the force, he joined the department almost 25 years ago as a patrol officer, worked his way up the brass ladder, and was awarded the top job in 2022.

Oak Brook was the first municipality in Illinois to deploy a drone as a first responder. One of the main reasons, says Strockis, was to reduce the number of high-speed chases, which are potentially dangerous to officers, suspects, and civilians. A drone is also a more effective and cost-efficient way to deal with suspects in fleeing vehicles, says Strockis. Police say there was the potential for a dangerous high-speed chase. Patrol cars raced to the scene. But the first unit to arrive was a drone. “It’s a force multiplier in that we’re able to do more with less,” says the chief, who spoke with me in his office at Oak Brook’s Village Hall.

The department’s drone autonomously launches from the roof of the building and responds to about 10 to 12 service calls per day, at speeds up to 45 miles per hour. It arrives at crime scenes before patrol officers in nine out of every 10 cases. Next door to Village Hall is the Oak Brook Police Department’s real-time crime center, a large room with two video walls that integrates livestreams from the first-responder drone, handheld drones, traffic cameras, license plate readers, and about a thousand private security cameras. When I visited, the two DFR operators demonstrated how the machine can fly itself or be directed to locations from a destination entered on Google Maps. They sent it off to a nearby forest preserve and then directed it to return to the rooftop base, where it docks automatically, changes batteries, and charges. After the demo, one of the drone operators logged the flight, as required by state law. Strockis says he is aware of the privacy concerns around using this technology but that protections are in place. For example, the drone cannot be used for random or mass surveillance, he says, because the camera is always pointed straight ahead during flight and does not angle down until it reaches its desired location. The drone’s payload does not include facial recognition technology, which is restricted by state law, he says. The drone video footage is invaluable, he adds, because “you are seeing the events as they’re transpiring from an angle that you wouldn’t otherwise be privy to.” It’s an extra layer of protection for the public as well as for the officers, says the chief: “For every incident that an officer responds to now, you have squad car and bodycam video. You likely have cell-phone video from the public, officers, complainants, from offenders. So adding this element is probably the best video source on a scene that the police are going to anyway.” Mark Wallace Executive director, Citizens to Abolish Red Light Cameras Mark Wallace wears several hats. By day he is a real estate investor and mortgage lender. But he is probably best known to many Chicagoans—especially across the city’s largely African-American communities on the South and West Sides—as a talk radio host for the station WVON and one of the leading voices against the city’s extensive network of red-light and speed cameras. For the past two decades, city officials have maintained that the cameras—which are officially known as “automated enforcement”—are a crucial safety measure. They are also a substantial revenue stream, generating around $150 million a year and a total of some $2.5 billion since they were installed.

Urged on by a radio listener, Mark Wallace started organizing against Chicago’s red-light and speed cameras, a substantial revenue stream for the city that has been found to disproportionately burden majority Black and Latino areas.AKILAH TOWNSEND “The one thing that the cameras have the ability to do is generate a lot of money,” Wallace says. He describes the tickets as a “cash grab” that disproportionately affects Black and Latino communities. A groundbreaking 2022 analysis by ProPublica found, in fact, that households in majority Black and Latino zip codes were ticketed at much higher rates than others, in part because the cameras in those areas were more likely to be installed near expressway ramps and on wider streets, which encouraged faster speeds. The tickets, which can quickly rack up late fees, were also found to cause more of a financial burden in such communities, the report found. These were some of the same concerns that many people expressed on the radio and in meetings, Wallace says. Chicago’s automated traffic enforcement began in 2003, and it became the most extensive—and most lucrative—such program in the country. About 300 red-light cameras and 200 speed cameras are set up near schools and parks. The cost of the tickets can quickly double if they are not paid or contested—providing a windfall for the city. Wallace began his advocacy against the cameras soon after arriving at the radio station in the early 2010s. A younger listener called in and said, he recalls, “that he enjoyed the information that came from WVON but that we didn’t do anything.” The comment stuck with him, especially in light of WVON’s storied history. The station was closely involved in the civil rights movement of the 1960s and broadcast Martin Luther King Jr.’s speeches during his Chicago campaign. Wallace hoped to change the caller’s perception about the station. He had firsthand experience with red-light cameras, having been ticketed himself, and decided to take them on as a cause. He scheduled a meeting at his church for a Friday night, promoting it on his show. “More than 300 people showed up,” he remembers, chatting with me in the spacious project studio and office in the basement of his townhouse on the city’s South Side. “That said to me there are a lot of people who see this inequity and injustice.” Wallace began using his platform on WVON—The People’s Show—to mobilize communities around social and economic justice, and many discussions revolved around the automated enforcement program. The cause gained traction after city and state officials were found to have taken thousands of dollars from technology and surveillance companies to make sure their cameras remained on the streets. Wallace and his group, Citizens to Abolish Red Light Cameras, want to repeal the ordinances authorizing the city’s camera programs. That hasn’t happened so far, but political pressure from the group paved the way for a Chicago City Council ordinance that required public meetings before any red-light cameras are installed, removed, or relocated. The group hopes for more restrictions for speed cameras, too. “It was never about me personally. It was about ensuring that we could demonstrate to people that you have power,” says Wallace. “If you don’t like something, as Barack Obama would say, get a pen and clipboard and go to work to fight to make these changes.” Jonathan Manes Senior counsel, MacArthur Justice Center Derick Scruggs, a 30-year-old father and licensed armed security guard, was working in the parking lot of an AutoZone on Chicago’s Southwest Side on April 19, 2021. That’s when he was detained, interrogated, and subjected to a “humiliating body search” by two Chicago police officers, Scruggs later attested. “I was just doing my job when police officers came at me, handcuffed me, and treated me like a criminal—just because I was near a ShotSpotter alert,” he says. The officers found no evidence of a shooting and released Scruggs. But the next day, the police returned and arrested him for an alleged violation related to his security guard paperwork. Prosecutors later dismissed the charges, but he was held in custody overnight and was then fired from his job. “Because of what they did,” he says, “I lost my job, couldn’t work for months, and got evicted from my apartment.” Jonathan Manes litigated cases related to detentions at Guantanamo Bay and the legality of drone strikes before turning his attention to Chicago’s implementation of gunshot detection technology.AKILAH TOWNSEND Scruggs is believed to be among thousands of Chicagoans who’ve been questioned, detained, or arrested by police because they were near the location of a ShotSpotter alert, according to an analysis by the City of Chicago Office of Inspector General. The case caught the attention of Jonathan Manes, a law professor at Northwestern and senior counsel at the MacArthur Justice Center, a public interest law firm. Manes previously worked in national security law, but when he joined the justice center about six years ago, he chose to focus squarely on the intersection of civil rights with police surveillance and technology. “My goal was to identify areas that weren’t well covered by other civil rights organizations but were a concern for people here in Chicago,” he says. “There is a need for much broader structural change to how the city chooses to use surveillance technology and then deploys it.” Jonathan Manes, senior counsel, MacArthur Justice Center And when he and his colleagues looked into ShotSpotter, they revealed a disturbing problem: The system generated alerts that yielded no evidence of gun-related crimes but were used by police as a pretext for other actions. There seemed to be “a pattern of people being stopped, detained, questioned, sometimes arrested, in response to a ShotSpotter alert—often resulting in charges that have nothing to do with guns,” Manes says. The system also directed a “massive number of police deployments onto the South and West Sides of the city,” Manes says. Those regions are home to most of Chicago’s Black and Latino residents. The research showed that 80% of the city’s Black population but only 30% of its white population lived in districts covered by the system. Manes brought Scruggs’s case into a lawsuit that he was already developing against the city’s use of ShotSpotter. In late 2025, he and his colleagues reached a settlement that prohibits police officers from doing what they did in Scruggs’s case—stopping or searching people simply because they are near the location of a gunshot detection alert. Chicago had already decommissioned ShotSpotter in 2024, but the agreement will cover any future gunshot detection systems. Manes is carefully watching to see what happens next. Though Manes is pleased with the settlement, he points out that it narrowly focused on how police resources were used after the gunshot detection system was operational. “There is a need for much broader structural change to how the city chooses to use surveillance technology and then deploys it,” he adds. He supports laws that require disclosure from local officials and law enforcement about what technologies are being proposed and how civil rights could be affected. More than two dozen jurisdictions nationwide have adopted surveillance transparency laws, including San Francisco, Seattle, Boston, and New York City. But so far Chicago is not on that list. Rod McCullom is a Chicago-based science and technology writer whose focus areas include AI, biometrics, cognition, and the science of crime and violence.

Nvidia lines up partners to boost security for industrial operations

Akamai extends its micro-segmentation and zero-trust security platform Guardicore to run on Nvidia BlueField GPUs The integration offloads user-configurable security processes from the host system to the Nvidia BlueField DPU and enables zero-trust segmentation without requiring software agents on fragile or legacy systems, according to Akamai. Organizations can implement this hardware-isolated, “agentless” security approach to help align with regulatory requirements and lower their risk profile for cyber insurance. “It delivers deep, out-of-band visibility across systems, networks, and applications without disrupting operations. Security policies can be enforced in real time and are capable of creating a strong protective boundary around critical operational systems. The result is trusted insight into operational activity and improved overall cyber resilience,” according to Akamai. Forescout works with Nvidia to bring zero-trust technology to OT networks Forescout applies network segmentation to contain lateral movement and enforce zero-trust controls. The technology would be further integrated into partnership work already being done by the two companies. By running Forescout’s on-premises sensor directly on the Nvidia BlueField, part of Nvidia Cybersecurity AI platform, customers can offload intensive computing tasks, such as deep packet inspections. This speeds up data processing, enhances asset intelligence, and improves real-time monitoring, providing security teams with the insights needed to stay ahead of emerging threats, according to Forescout. Palo Alto to demo Prisma AIRS AI Runtime Security on Nvidia BlueField DPU Palo Alto Networks recently partnered with Nvidia to run its Prisma AI-powered Radio Security(AIRs) package on the Nvidia BlueField DPU and will show off the technology at the conference. The technology is part of the Nvidia Enterprise AI Factory validated design and can offer real-time security protection for industrial network settings. “Prisma AIRS AI Runtime Security delivers deep visibility into industrial traffic and continuous monitoring for abnormal behavior. By running these security services on Nvidia BlueField, inspection

Pure Storage becomes Everpure, acquires 1touch

Other recent research confirms this. In an October Cisco survey of over 8,000 AI leaders, only 35% of companies have clean, centralized data with real-time integration for AI agents. And by 2027, according to IDC, companies that don’t prioritize high-quality, AI-ready data will struggle scaling gen AI and agentic solutions, resulting in a 15% productivity loss. “Every enterprise is talking about AI, but most aren’t AI ready because their data is fragmented and poorly cataloged,” says Brad Gastwirth, global head of research and market intelligence at Circular Technology, a supply chain consultancy. “If Everpure can help turn storage into a structured, intelligent data foundation, that could materially shorten the path from proof of concept to production AI.” It’s not an easy process. It could take years to shift from being viewed primarily as a storage hardware company to a data platform company, Gastwirth says. “There is product integration to get right, but there is also a commercial shift. Sales teams need to sell differently, customers need to budget differently, and the market needs proof points.” And there are many companies in the race to be the data platform for AI. “The difference is where it sits in the stack,” he says. “If Everpure can bake more intelligence directly into the core storage layer instead of layering tools on top, that can actually simplify things.” Putting the control layer closer to the data can be helpful as companies deploy agentic AI. AI agents need to have good access to data to function well, whether as part of their training, in RAG embedding, or via MPC servers. But ensuring that agents only access the data they’re supposed to is a challenge. “The shift to agentic AI is a big reason why you’d want to have your data intelligence tied to your data

Peptides are everywhere. Here’s what you need to know.

MIT Technology Review Explains: Let our writers untangle the complex, messy world of technology to help you understand what’s coming next. You can read more from the series here. Want to lose weight? Get shredded? Stay mentally sharp? A wellness influencer might tell you to take peptides, the latest cure-all in the alternative medicine arsenal. People inject them. They snort them. They combine them into concoctions with superhero names, like the Wolverine stack. Matt Kaeberlein, a longevity researcher, first started hearing about peptides a few years ago. “At that point it was mostly functional medicine doctors that were using peptides,” he says, referring to physicians who embrace alternative medicine and supplements. “In the last six months, it’s kind of gone crazy.” Peptides have gone mainstream. At the health-technology startup Superpower in Los Angeles, employees can get free peptide shots on Fridays. At a health food store in Phoenix, a sidewalk sign reads, “We have peptides!” At a tae kwon do center in South Carolina, a peptide wholesaler hosts an informational evening. On social media, they’re everywhere. And that popularity seems poised to grow; Department of Health and Human Services secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has promised to end the FDA’s “aggressive suppression” of peptides.

The benefits and risks of many of these compounds, however, are largely unknown. Some of the most popular peptides have never been tested in human trials. They are sold for research purposes, not human consumption. Some are illegal knockoffs of wildly successful weight-loss medicines. The vast majority come from China, a fact that has some legislators worried. Last week, Senator Tom Cotton urged the head of the FDA to crack down on illegal shipments of peptides from China. In the absence of regulatory oversight, some people are sending the compounds they purchase off for independent testing just to ensure that the product is legit. What is a peptide? A peptide is simply a short string of amino acids, the building blocks of proteins. “Scientists generally think of peptides as very small protein fragments, but we don’t really have a precise cutoff between a peptide and a protein,” says Paul Knoepfler, a stem-cell researcher at the University of California, Davis. Insulin is a peptide, as is human growth hormone. So are some neurotransmitters, like oxytocin.

But when wellness influencers talk about peptides, they’re often referring to particular compounds—formulated as injections, pills, or nasal sprays—that have become trendy lately. Some of these peptides are FDA-approved prescription medications. GLP-1 medicines, for example, are approved to treat diabetes and obesity but are also easily accessible online to almost anyone who wants to use them. Many sites sell microdoses of GLP-1s with claims that they can “support longevity,” reduce cognitive decline, or curb inflammation. Many more peptides are experimental. “The majority fall into the unapproved bucket,” says Kaeberlein, who is chief executive officer of Optispan, a Seattle-based health-care technology company focused on longevity. That bucket includes drugs that promote the release of growth hormones, like TB-500, CJC-1295, and ipamorelin, and compounds said to promote tissue repair and wound healing, like BPC-157 and GHK-Cu. It’s primarily these unapproved compounds that have raised concerns. “Anybody can set up an online shop selling research-grade peptides,” says Tenille Davis, a pharmacist and chief advocacy officer at the Alliance for Pharmacy Compounding, a trade organization representing more than 600 pharmacies. “And nobody knows what’s even in the vials.” It’s not just fitness gurus, biohackers, and longevity fanatics who are taking these experimental drugs. Kaeberlein recalls hearing about an acquaintance whose doctor prescribed her unapproved peptides. She was “just a typical upper-middle-class woman,” he says. “That’s when it really hit me that this has sort of gone relatively mainstream.” What do peptides do? All kinds of things, purportedly. GHK-Cu is supposed to help with wound healing and collagen production. BPC-157 is said to promote tissue repair and curb inflammation, TB-500 to foster blood vessel formation. Here’s the caveat: The evidence for these benefits comes largely from animal studies and online testimonials, not human trials. “There’s no human clinical evidence to show that they even do what people are claiming that they do,” says Stuart Phillips, a muscle physiologist at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. “So it could be just a giant rip-off.” Some experimental peptides probably do have beneficial wound healing properties or regenerative effects, Kaeberlein says. For BPC-157, for example, “the animal data is compelling,” he says. But there are still plenty of unknowns: What is the right dosage? How long should you take it? What’s the best way to administer it? Those are questions that can be answered only through rigorous clinical trials. In the absence of those studies, doctors “just make up their own protocols,” he says. Some consumers go the DIY route, reconstituting powdered peptides and injecting their own concoctions at home. So why am I seeing ads for these peptide therapies if they’re not approved? Federal law prohibits companies from marketing medications that haven’t been approved. That includes most peptides, which are regulated as small molecules, not dietary supplements. (Two notable exceptions are collagen peptides and creatine peptides, often sold as powders.) The law is designed to protect consumers from drugs that haven’t been proved safe and effective. But it doesn’t stop labs from making peptides for research purposes. “Most of the peptides being consumed in the marketplace now are being sold by these online companies that are selling them labeled for research use only,” Davis says. The vials often bear disclaimers that clearly say as much: “For research use only” or “Not for human consumption.” It’s illegal to market these products for human use, but “the websites make it pretty clear that the buyers are intended to be using these products themselves,” she says.

The practice isn’t legal, but enforcement has been sporadic. “FDA sends warning letters, shuts down companies. But because it’s all online, they have a really hard time keeping up with these entities,” Davis says. And companies have plenty of incentive to keep illegally marketing the products. “They can make millions of dollars without having to spend money and time doing research,” Knoepfler says. “It’s a cash grab.” Compounding pharmacies, which are legally allowed to create bespoke medications by mixing bulk active ingredients, often get requests to dispense peptides, but most peptides don’t meet the eligibility criteria for compounding. This has always been the case, but in 2023 the FDA explicitly added several common experimental peptides to the list of bulk substances that cannot be compounded because of safety concerns. “It put an exclamation point on policy that was already in place,” Davis says. Many GLP-1 medications are available from compounding pharmacies. That used to be accepted because the drugs were in short supply. Now, however, supplies of most of these medications are stable, and sellers are under increasing pressure from regulators to stop mass-marketing these drugs. What’s the harm in trying them? Peptides sold for research purposes come from labs with little regulatory oversight. “When you buy stuff online intended for research grade, you have no idea what’s in the vial that you’re getting. You have no idea the sterility practices that it was manufactured under, or what sort of impurities might be in the vial,” Davis says. Phillips has heard some people say they send their peptides for third-party testing to ensure that they’re pure, “like it’s some kind of flex,” he says. “And I’m like, ‘Well, you just proved that this stuff lives in the shadows, for crying out loud.’” Finnrick Analytics, a peptide-testing startup in Austin, Texas, has analyzed the purity and potency of more than 5,000 samples of 15 different peptides from 173 vendors. The results show that the quality varies substantially from vendor to vendor and even batch to batch. For example, the company tested nearly 450 samples of BPC-157 from 64 vendors. In some cases, the vials sold as BPC-157 didn’t contain the compound at all. In those that did, the purity varied from about 82% to 100%. Perhaps more worrying, 8% of all the peptide samples Finnrick tested had measurable levels of endotoxins, bacterial fragments that can cause fever and chills or, in larger doses, septic shock. The health risks aren’t just hypothetical. In 2025, two women had to be hospitalized and placed on ventilators after receiving peptide injections at a longevity conference in Las Vegas. Both recovered, and it’s still not clear whether they reacted to the peptides themselves or to some impurity in the vials.

“The idea that all peptides are safe and all peptides are natural is just nonsense,” Kaeberlein says. “I tend to consider myself fairly libertarian when it comes to what people want to do for their health,” he adds. “If you want to take an experimental drug, that’s up to you.” But the problem with unregulated experimental therapies is that it’s exceedingly difficult to assess benefit and harm. “The relatively small percentage of people that are bad actors will be bad actors, and they will dishonestly market this stuff to people who aren’t equipped to really understand the true risks and rewards,” he says. And, like any drug, peptides come with a risk of side effects. For approved medications, these are detailed right on the package insert. But for many experimental peptides, there hasn’t been enough research to understand what those side effects might be. Some researchers have warned that peptides that promote growth or blood vessel formation might also foster the growth of cancers.

For competitive athletes who use peptides, meanwhile, the risks include not just possible health problems but suspension. Some peptides, like BPC-157, are banned by the World Anti-Doping Agency. The FDA has undergone a pretty substantial overhaul under the Trump administration. Are the regulations around peptides likely to change? I don’t have a crystal ball, but it seems likely. In May 2025, US health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. joined the longevity enthusiast and biohacker Gary Brecka on his podcast The Ultimate Human and promised to “end the war at FDA against alternative medicine—the war on stem cells, the war on chelating drugs, the war on peptides.” Knoepfler anticipates that Kennedy will force the FDA to allow compounding of some of the most popular peptides, like BPC-157 and GHK-Cu. “Such a step would put public health at great risk, while giving compounders and likely wellness influencers a lot more profit,” he says. The FDA seems intent on cracking down on GLP-1 copycats, however. In early February, commissioner Marty Makary posted on X that the agency would take “swift action against companies mass-marketing illegal copycat drugs, claiming they are similar to FDA-approved products.”

The human work behind humanoid robots is being hidden

This story originally appeared in The Algorithm, our weekly newsletter on AI. To get stories like this in your inbox first, sign up here. In January, Nvidia’s Jensen Huang, the head of the world’s most valuable company, proclaimed that we are entering the era of physical AI, when artificial intelligence will move beyond language and chatbots into physically capable machines. (He also said the same thing the year before, by the way.) The implication—fueled by new demonstrations of humanoid robots putting away dishes or assembling cars—is that mimicking human limbs with single-purpose robot arms is the old way of automation. The new way is to replicate the way humans think, learn, and adapt while they work. The problem is that the lack of transparency about the human labor involved in training and operating such robots leaves the public both misunderstanding what robots can actually do and failing to see the strange new forms of work forming around them. Consider how, in the AI era, robots often learn from humans who demonstrate how to do a chore. Creating this data at scale is now leading to Black Mirror–esque scenarios. A worker in Shanghai, for example, recently spent a week wearing a virtual-reality headset and an exoskeleton while opening and closing the door of a microwave hundreds of times a day to train the robot next to him, Rest of World reported. In North America, the robotics company Figure appears to be planning something similar: It announced in September it would partner with the investment firm Brookfield, which manages 100,000 residential units, to capture “massive amounts” of real-world data “across a variety of household environments.” (Figure did not respond to questions about this effort.)

Just as our words became training data for large language models, our movements are now poised to follow the same path. Except this future might leave humans with an even worse deal, and it’s already beginning. The roboticist Aaron Prather told me about recent work with a delivery company that had its workers wear movement-tracking sensors as they moved boxes; the data collected will be used to train robots. The effort to build humanoids will likely require manual laborers to act as data collectors at massive scale. “It’s going to be weird,” Prather says. “No doubts about it.” Or consider tele-operation. Though the endgame in robotics is a machine that can complete a task on its own, robotics companies employ people to operate their robots remotely. Neo, a $20,000 humanoid robot from the startup 1X, is set to ship to homes this year, but the company’s founder, Bernt Øivind Børnich, told me recently that he’s not committed to any prescribed level of autonomy. If a robot gets stuck, or if the customer wants it to do a tricky task, a tele-operator from the company’s headquarters in Palo Alto, California, will pilot it, looking through its cameras to iron clothes or unload the dishwasher.

This isn’t inherently harmful—1X gets customer consent before switching into tele-operation mode—but privacy as we know it will not exist in a world where tele-operators are doing chores in your house through a robot. And if home humanoids are not genuinely autonomous, the arrangement is better understood as a form of wage arbitrage that re-creates the dynamics of gig work while, for the first time, allowing physical tasks to be performed wherever labor is cheapest. We’ve been down similar roads before. Carrying out “AI-driven” content moderation on social media platforms or assembling training data for AI companies often requires workers in low-wage countries to view disturbing content. And despite claims that AI will soon enough train on its outputs and learn on its own, even the best models require an awful lot of human feedback to work as desired. These human workforces do not mean that AI is just vaporware. But when they remain invisible, the public consistently overestimates the machines’ actual capabilities. That’s great for investors and hype, but it has consequences for everyone. When Tesla marketed its driver-assistance software as “Autopilot,” for example, it inflated public expectations about what the system could safely do—a distortion a Miami jury recently found contributed to a crash that killed a 22-year-old woman (Tesla was ordered to pay $240 million in damages). The same will be true for humanoid robots. If Huang is right, and physical AI is coming for our workplaces, homes, and public spaces, then the way we describe and scrutinize such technology matters. Yet robotics companies remain as opaque about training and tele-operation as AI firms are about their training data. If that does not change, we risk mistaking concealed human labor for machine intelligence—and seeing far more autonomy than truly exists.

The Download: Chicago’s surveillance network, and building better bras

This is today’s edition of The Download, our weekday newsletter that provides a daily dose of what’s going on in the world of technology. Inside Chicago’s surveillance panopticon Chicago has tens of thousands of surveillance cameras—up to 45,000, by some estimates. That’s among the highest numbers per capita in the US. Chicago boasts one of the largest license plate reader systems in the country, and the ability to access audio and video surveillance from independent agencies such as the Chicago Public Schools, the Chicago Park District, and the public transportation system as well as many residential and commercial security systems such as Ring doorbell cameras.Law enforcement and security advocates say this vast monitoring system protects public safety and works well.

But activists and many residents say it’s a surveillance panopticon that creates a chilling effect on behavior and violates guarantees of privacy and free speech. Read the full story. —Rod McCullom

Job titles of the future: Breast biomechanic Twenty years ago, Joanna Wakefield-Scurr was having persistent pain in her breasts. Her doctor couldn’t diagnose the cause but said a good, supportive bra could help. A professor of biomechanics, Wakefield-Scurr thought she could do a little research and find a science-backed option. Two decades later, she’s still looking.Wakefield-Scurr now leads an 18-person team at the Research Group in Breast Health at the University of Portsmouth in the UK. And as more women take up high-impact sports, the need to understand what makes a good bra grows, she says her lab can’t keep up with demand. Read the full story. —Sara Harrison These stories are both from the next print issue of MIT Technology Review magazine, which is all about crime. If you haven’t already, subscribe now to receive future issues once they land. The must-reads I’ve combed the internet to find you today’s most fun/important/scary/fascinating stories about technology.

1 Inside ICE’s plans to build huge detention centers across the USThe identities of the personnel who authorized it have been revealed in metadata. (Wired $)+ A UK tourist with a valid visa was detained by ICE for six weeks. (The Guardian) 2 The UAE says it was targeted by a wave of AI-backed cyberattacksAuthorities said the attacks marked a major shift in methods, but didn’t elaborate. (Bloomberg $)+ New cybersecurity rules are hobbling small defense suppliers. (Reuters)+ AI is already making online crimes easier. It could get much worse. (MIT Technology Review)3 What does the public really think about AI?Tech leaders are worried they might not be fully onboard with their missions. (NYT $)+ How social media encourages the worst of AI boosterism. (MIT Technology Review) 4 It looks like X really is pushing its users further to the rightAs well as attracting more conservative thinkers in the first place. (NY Mag $)+ The platform is currently disputing a major European fine. (Politico $)5 Meet the farmers standing up to data center buildersThey’re turning down deals worth millions for the land they’ve worked for decades. (The Guardian)+ A data center venture launched at the White House isn’t delivering on its promises. (The Information $)+ Data centers are amazing. Everyone hates them. (MIT Technology Review) 6 America has a plan to fight back against China’s AIIt hopes to send Tech Corps volunteers around the world to promote its own national efforts. (Rest of World)+ China’s plan to lure in new AI customers? Bubble tea. (FT $)+ The State of AI: Is China about to win the race? (MIT Technology Review) 7 Clouds are a major climate problem ☁️They’re making it harder for scientists to model the weather accurately. (Quanta Magazine)+ The building legal case for global climate justice. (MIT Technology Review) 8 AI is still hopeless at reading PDFsBut companies keep deploying it across work systems anyway. (The Verge) 9 A “Fitbit for farts” could help analyze your gastrointestinal healthIf you don’t mind wearing a sensor tucked into your underwear, that is. (WSJ $)10 Gen Z is fascinated by corporate culture 💼TikTok’s “WorkTok” videos are very effective at romanticizing the daily grind. (FT $)

Quote of the day “It also takes a lot of energy to train a human. It takes like 20 years of life and all of the food you eat during that time before you get smart.”

—Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, compares the environmental impact of training AI’s vast models to the effort required to train a human during an event in India, TechCrunch reports. One more thing How one mine could unlock billions in EV subsidiesOn a pine farm north of the tiny town of Tamarack, Minnesota, Talon Metals has uncovered one of America’s densest nickel deposits—and now it wants to begin extracting it.If regulators approve the mine, it could mark the starting point in what the company claims would become the country’s first complete domestic nickel supply chain, running from the bedrock beneath the Minnesota earth to the batteries in electric vehicles across the nation.MIT Technology Review wanted to provide a clearer sense of the law’s on-the-ground impact by zeroing in on a single project and examining how these rich subsidies could be unlocked at each point along the supply chain. Take a look at what we found out. —James Temple

We can still have nice things A place for comfort, fun and distraction to brighten up your day. (Got any ideas? Drop me a line or skeet ’em at me.) + Alysa Liu’s gold medal-winning Winter Olympics figure skating route is truly amazing.+ Mmm, delicious ancient Roman pizza.+ It’s not every day you find 2,000 year-old footprints while walking your dog 👣+ Nature is full of surprises, and so are the winners of this year’s Sony World Photography Awards.

Inside Chicago’s surveillance panopticon

Early on the morning of September 2, 2024, a Chicago Transit Authority Blue Line train was the scene of a random and horrific mass shooting. Four people were shot and killed on a westbound train as it approached the suburb of Forest Park. The police swiftly activated a digital dragnet—a surveillance network that connects thousands of cameras in the city. The process began with a quick review of the transit agency’s surveillance cameras, which captured the alleged gunman shooting the victims execution style. Law enforcement followed the suspect, through real-time footage, across the rapid-transit system. Police officials circulated the images to transit staff and to thousands of officers. An officer in the adjacent suburb of Riverdale recognized the suspect from a previous arrest. By the time he was captured at another train station, just 90 minutes after the shooting, authorities already had his name, address, and previous arrest history. Little of this process would come as much surprise to Chicagoans. The city has tens of thousands of surveillance cameras—up to 45,000, by some estimates. That’s among the highest numbers per capita in the US. Chicago boasts one of the largest license plate reader systems in the country, and the ability to access audio and video surveillance from independent agencies such as the Chicago Public Schools, the Chicago Park District, and the public transportation system as well as many residential and commercial security systems such as Ring doorbell cameras. Law enforcement and security advocates say this vast monitoring system protects public safety and works well. But activists and many residents say it’s a surveillance panopticon that creates a chilling effect on behavior and violates guarantees of privacy and free speech. Black and Latino communities in Chicago have historically been targeted by excessive policing and surveillance, says Lance Williams, a scholar of urban violence at Northeastern Illinois University. That scrutiny has created new problems without delivering the promised safety, he suggests. In order to “solve the problem of crime or violence and make these communities safer,” he says, “you have to deal with structural problems,” such as the shortage of livable-wage jobs, affordable housing, and mental-health services across the city.

Recent years have seen some effective pushback against the surveillance. Until recently, for example, the city was the largest customer of ShotSpotter acoustic sensors, which are designed to detect gunfire and alert police. The system was introduced in a small area on the South Side in 2012. By 2018, an area of about 136 square miles—some 60% of the city—was covered by the acoustic surveillance network. Critics questioned ShotSpotter’s effectiveness and objected that the sensors were installed largely in Black and Latino neighborhoods. Those critiques gained urgency with the fatal shooting in March 2021 of a 13-year-old, Adam Toledo, by police responding to a ShotSpotter alert. The tragedy became the touchstone of the #StopShotSpotter protest movement and one of the major issues in Brandon Johnson’s successful mayoral campaign in 2023. When he reached office, Johnson followed through, ending the city’s contract with SoundThinking, the San Francisco Bay Area company behind ShotSpotter. In total, it’s estimated the city paid more than $53 million for the system.